Abstract

About 15% of all cancer diagnoses in western Europe are for prostate cancer, and many cancer patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals communicate over social media to discuss disease, treatments, side effects, concerns, and support. Social media listening can help identify unmet needs and fill gaps in patient treatment pathways. The authors wanted to understand the topics discussed, emotional tonality and sentiment of conversations, and specific behaviours exhibited. For this study, relevant mentions of prostate cancer were harvested using approved search syntax with social media listening technology. A representative sample across market datasets was used to uncover in-depth insights regarding emotions, key topics, perception, and behaviours, followed by an analysis of the qualitative aspects of the conversation to highlight emotions and behaviours related to the authors’ research objectives. About a quarter of the conversations were related to metastatic cancer, and non-metastatic cancer. Peaks coincided with social movements, such as ‘Movember’ and World Cancer Day. Most conversations about prostate cancer, whether metastatic or not, were driven by anxiety, fear, and worry. Throughout the patient journey, there was an underlying dread of disease progression, with peaks and troughs in emotion coinciding with diagnosis, metastases, treatment, and treatment failure. Patients often felt that they were left by their physicians to make their own decisions regarding treatment and used social media to communicate with their peers and caregivers to gain information. Via social media, patients shared information about disease status, treatment options, side effects, and quality of life, while offering each other emotional support.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of prostate cancer in the overall cancer population in western Europe is between 10% and 15%; it is the leading cause of non-cutaneous cancer in many parts of the world.1 From a worldwide population of around 7.7 billion people, approximately 2.7 billion use social media.2,3 As of January 2019, there were 2.2 billion active users of Facebook, 1.0 billion for Instagram, and 326.0 million for Twitter.4 Moreover, social media has become a heavily used tool in healthcare, where patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals (HCP) increasingly engage among themselves and between each other via various channels. Such conversations cover a variety of topics, including disease, treatment, side effects, concerns, and support.

Rationale

Considering the incidence and mortality rates of prostate cancer in western Europe, and how much social media is used for communication,5-7 this study was developed to explore online conversations related to prostate cancer. The objective was to understand the topics discussed, the emotional tonality and sentiment of these discussions, and specific behaviours exhibited. The intention was also to understand conversations related to disease progression and development of metastases from patients and caregivers, on which social media channels these conversations were taking place most frequently, and between whom.

Methods

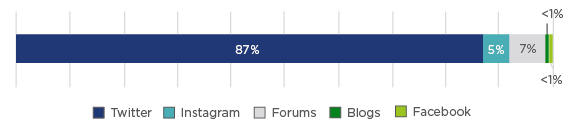

This was a qualitative ethnographic study; a netnography for the conversations among prostate cancer patients and their caregivers over digital platforms.8,9 From the 1st of June 2016 to the 31st of May 2018, data were collected from social media channels in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK (Figure 1). Conversations were harvested across publicly available social media, including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook public pages, news and review sites, blogs, and forums, spanning >85 million sites. The total prostate cancer conversation landscape included non-patient discussions and other irrelevant areas (e.g., promotions and bot accounts). Data were cleaned to remove the most irrelevant content, and filter terms were applied to isolate the relevant patient and caregiver (and to a lesser extent, HCP) conversations for qualitative deep dive analysis.

Figure 1: Social media channel distribution.

The search syntax included key words such as ‘prostate cancer’, ‘prostate metastases’, and ‘metastatic free survival’, which were translated into the native languages of the respective countries. The search syntax identified 546,324 posts related to prostate cancer, of which 955 were randomly sampled across the countries and then manually coded by native language analysts to identify author type (e.g., patient or caregiver), and categorised in terms of conversation topics, emotions conveyed, and behaviours exhibited. Facebook was included, but public pages only. Details of the syntax can be provided upon request.

For the purposes of data protection, all verbatim conversations have been paraphrased in this paper.

RESULTS

Channels of Choice

The most frequently used channels were Twitter, followed by Instagram, Facebook, forums, and blogs (except in Germany, see Figure 1). Key forum sites within each of the countries were also used to discuss prostate cancer. The proportion of online patient conversation was greater in the UK, France, and Germany compared to Spain and Italy. Most of the online discussions took place among patients and caregivers.

Conversation Volume

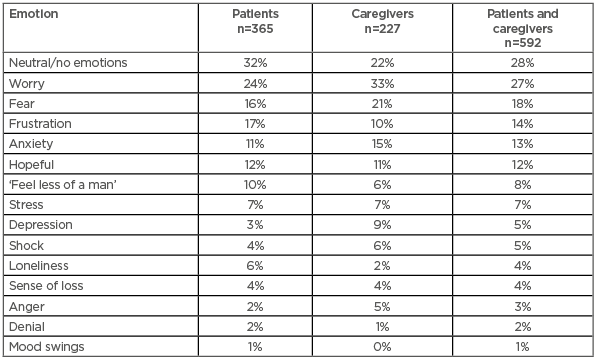

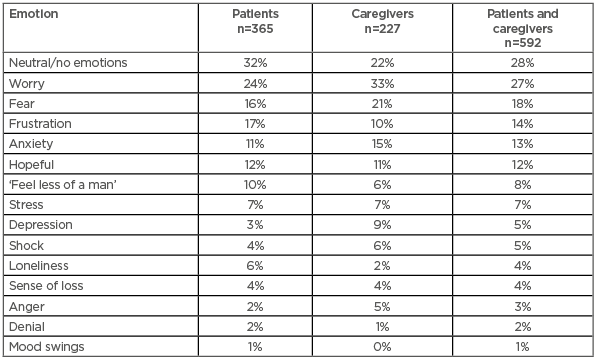

Most conversations among patients and caregivers included neutral language; however, the most frequently used emotive words were ‘worry’, ‘fear’, ‘frustration’, and ‘anxiety’ (Table 1). Notably, 24% of conversations were related to metastatic disease versus 22% related to being metastatic-free (Figure 2). The volume of conversations peaked at just under 15,000 in November 2016 and just under 12,000 in November 2017 because of the ‘Movember’ charity movement aimed at highlighting health issues specific to men, including prostate cancer. Other peaks were also observed throughout the year, for example, smaller spikes were seen during February and early March 2018 relating to World Cancer Day (4th February), and additionally when UK celebrity Stephen Fry revealed his prostate cancer diagnosis.

Table 1: Proportion of use of emotive words in conversations involving patients and caregivers.

Figure 2: Total conversations about prostate cancer.

*Based on a manually coded, representative sample of 955 conversations.

The patients’ online conversations about prostate cancer, whether concerning metastases or not, were driven by anxiety, fear, and worry. Other predominant emotions included stress, loneliness, and feeling like ‘less of a man’, typically because of side effects from treatment such as impotence and incontinence (Table 1). Throughout the patient journey, there were peaks and troughs in levels of fear. The peaks coincided with diagnosis of non-metastatic or metastatic prostate cancer, but the fear of disease progression was present throughout, punctuated by treatment initiation; however, the fear peaked again upon failure of treatments and rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels.

Most of the online discussion took place among patients and caregivers (HCP represented only a small proportion of the prostate cancer conversations taking place online). The patient conversation represented a greater proportion of the online discussion in Germany (54%), France (51%), and the UK (42%) compared to Italy (30%) and Spain (19%; data not shown). In contrast, the caregiver conversation represented a greater proportion of the online discussion in Spain (40%) and France (30%) compared to Germany (27%), Italy (23%), and the UK (19%; data not shown).

Disease Knowledge

Patients tended to be very knowledgeable about their disease and the treatments available to them, and openly shared their stories. Their recollections were often detailed with medical terminology, referencing key milestones with test results and treatments, and delivered with little emotion by simply sharing facts. One patient from the UK commented:

“After my annual check-up, the Drs surgery called to say that my PSA had risen to 5.7 from negligible the year before and that they were investigating me for prostate cancer. My initial rectal exam felt normal, but within a week I had a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and a week later saw the consultant urologist where I give another blood sample and had another rectal exam; 10 days later I was back at the consultant urologist for results/follow-up, which showed some abnormalities and my PSA had risen to 6.4, so they performed an immediate transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy.”

Conversations between patients and caregivers focussed on treatments, PSA levels and Gleason scores, their relationship with their HCP, and disease progression. Conversations about disease progression and its impacts were ongoing throughout the patient journey. Regarding treatment, conversations focussed on therapy options, efficacy, side effects, and level of invasiveness. Regarding side effects, patients would often cite concerns over potential treatments they were recommended and sought out information and reassurance from others. Efficacy (or the potential ineffectiveness of treatment) was often discussed among patients (and caregivers) with a view to helping decide which treatment option to proceed with. Invasiveness of interventions was a key concern for many when considering surgery, because patients and caregivers both asked questions (e.g., how ‘traumatic’ was the procedure) and shared experiences about invasive procedures. Disease progression was discussed in relation to PSA levels and Gleason scores as benchmarks for progression and severity. Social media was also used by patients to vent their frustrations about interactions with physicians, and to either challenge or validate the advice they were given.

Treatments

Patients engaged in discussions online, seeking second opinions from other patients about treatment plans. Conversations often revolved around how physicians presented various treatment options with top-level information but firmly left the decision about treatment with the patients. This was a catalyst for patients conducting their own research and seeking answers online to help reach their own decisions about treatment. Consequently, patients largely felt unsupported by their physicians and overwhelmed with the choices ahead of them. Patients often reported feeling under pressure to make the ‘right’ choice, fearful of regretting their decision if treatment was unsuccessful or resulted in significant side effects. Typically, conversations among patients and caregivers about treatments included surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, reflecting recommendations from their physicians.

Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels and Gleason Scores

Patients typically used PSA levels and Gleason scores to track the progression and severity of their disease and took an active role in management. However, this also led to anxiety because of the perception that increasing PSA levels were related to ineffective treatment and therefore metastases, meaning a prompt for action. Patients were justified in their anxiety because of research linking increasing PSA levels to the development of castrate-resistant disease.

Relationships with Healthcare Providers

The tone of the conversations about the relationship that patients and caregivers had with their physicians was often negative. Patients engaged with social media for second opinions because of their fears about decisions surrounding treatment and to vent their frustrations about the lack of information imparted by their physician regarding treatment options and side effects, as well as the feeling that their physician did not take their treatment seriously. One patient in Germany commented:

“If I’m honest I just feel a bit left alone by my doctors, my radiation doctor will only see me again in a year, my urologist I see every 3 months only very briefly for an ultrasound (blood test and hormone injection are done by the medical assistant) and at my family doctor I feel somehow out of place.”

Moreover, collating opinions from multiple physicians exacerbated confusion. Consequently, patients engaged with other patients to ask questions about treatment options and side effects, and to seek reassurance through emotional support. One patient in France commented:

“Consult an oncologist who should explain the different possibilities for treatment. Have them explain the side effects of each therapy to you. Take the time for reflection and discussion with your spouse.”

Conversations about Disease Progression

The progression of disease was discussed continuously throughout the patient journey, with fears expressed over their future. This conversation is prevalent among patients with and without metastatic prostate cancer, often occurring during discussions about treatment success and failure using PSA levels and Gleason scores as benchmarks.

Conversations not Involving Metastases

Across the five countries, patients frequently discussed the importance of not having metastases and how to delay progression, with progression being the source of much anxiety, fear, and worry. The drivers of these emotions for conversations were anxiety about high Gleason scores and changes to PSA levels, or the risk in delaying treatment while actively monitoring their PSA levels/Gleason scores (i.e., ‘watching and waiting’). These emotions led patients and caregivers to question HCP about the progression of their disease and the development of metastases so they could understand what to expect.

In tandem with the sense of relief of being free of metastatic disease, came the doubt and scepticism that patients were truly free of metastases because of their concerns about PSA levels and Gleason scores. Patients often sought second opinions from other patients to ensure that their disease had not spread beyond the prostate.

Delays to treatment, appointments, and test results during the patients’ journey added to their anxiety, fear, and worry. Patients felt out of control and unable to proactively manage their disease during the periods of ‘watching and waiting’, which prompted them to engage in discussions with their peers. One patient in the UK commented:

“I waited 10 days for an MRI result, getting myself more and more worked up, and when I got to the consultant, the result was clear. They performed an endoscopy on me under general anaesthetic, and saying “We don’t suspect cancer, this is just to be sure.” I was freaked out over going under general anaesthetic and having another long wait for results.”

Moreover, patients were aware of the development of castrate-resistant disease, which was viewed as a progression towards metastases with few options. Castrate-resistant prostate cancer is defined by disease progression despite androgen depletion therapy and may present as either a continuous rise in serum PSA levels, the progression of pre-existing disease, and/or the appearance of new metastases.10 Although such conversations were low in number, the possibility of progression was acknowledged. The patients’ anxieties remained despite being told by their physicians that there was only a small chance of disease progression, often requesting follow-ups soon after. One patient in Italy commented:

“PSA level increase might reveal the presence of castration-resistant prostate cancer. If this is confirmed, you will have to decide which is the best therapy option for you, considering that at the moment none of the new second-line drugs are available in the absence of metastasis.”

Conversations Involving Metastases

Patients diagnosed with metastatic disease discussed experiencing feelings of anxiety, fear, and worry. The drivers of conversations involving metastases were fears about shortened life expectancy, impact on quality of life, and understanding expectations from treatments and their side effects. Patients sought support online from their peers about treatment options, side effects, life expectancy, and day-to-day functions to live as normal a life as possible in the time that they had left. Most conversations amongst patients with metastases concerned side effects of treatment (usually chemotherapy).

At this stage, the tone of the conversations became less emotional, very matter of fact, clinical in nature, and more practical and functional about their PSA levels, Gleason scores, and signs and symptoms. One patient in Germany commented:

“My bone metastases have proliferated enormously and can be found practically everywhere from the head to the thigh, but mainly in the spine. But they cause no pain and are probably not yet vulnerable to break. Here are my questions: 1) How is this PSA progression assessed? Are there any fluctuations, can the value settle to a (low) level or do I have to expect a continuous/fast increase? 2) If yes, how can I continue? 3) What would you recommend regarding treatment?”

Some patients showed empowerment by conversing with fellow patients and caregivers with a view to taking control and fighting their disease, with a sense of urgency to make the ‘right’ decision about treatment quickly. Conversely, some patients showed a sense of resignation by either choosing alternative treatment options or giving up hope entirely. In contrast, the tone of caregivers showed more emotion and desperation about their loved ones’ diagnosis. One caregiver in France commented:

“Last year, I discovered that dad had undifferentiated prostate cancer, with a Gleason Scale of 10, a PSA level that went from 24 to 39 despite treatment. His testicles were removed, and the treatment had no effect meaning that his cancer was hormone resistant, so the Drs changed treatment. A bone scan showed the cancer had metastasised to the pelvic area. I’m worried about my dad, I don’t want to lose him, and he wants to stay with us too. Are his days numbered? Are there any testimonies? Please help me.”

CONCLUSION

This social media listening study provides unique and unprompted insights into what patients are mostly concerned about during their journey with prostate cancer, highlighting the areas where additional support should be provided to patients. In this study, the prospect of disease progression was a prevalent underlying fear throughout the patient journey. Close monitoring of PSA levels afforded patients a sense of control. Patients armed themselves with information on treatments, prognosis, side effects, and signs and symptoms to better recognise progression. Many patients felt unsupported and overwhelmed after physicians summarised their treatment options but firmly left decisions about treatment to patients. Once patients’ disease metastasised, their quality of life decreased largely because of treatment, and they became more resigned and failed to maintain the same level of empowerment that they had at the start of treatment. Conversely, caregivers became increasingly emotional and desperate. Without social media listening, such detail and depth of information would have been difficult to harvest. By understanding the anxieties, fears, and worries of patients, their unmet needs can be better supported through improved communication with HCP and patient support groups. For example, sharing information and advice on the management of current and potential treatment side-effects, the prospect of additional treatment options being available to rescue the patient, as well as professional counselling on dealing with the emotional impact of the disease, will help patients continue fighting their disease.