Meeting Summary

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) describes a group of rare inflammatory disorders that can damage small- and medium-sized blood vessels throughout the body, most notably affecting the kidneys, lungs, ears, nose, sinuses, and skin. Given the rarity of this condition, awareness, understanding, and knowledge around AAV can often be lacking, not only among patients themselves, but also physicians involved in disease diagnosis and clinical management.

During interviews carried out by EMJ during late 2020 and early 2021, four key opinion leaders in the field of AAV, two rheumatologists (Cristina Ponte and Joanna Robson) and two patient group representatives (John Mills and Peter Verhoeven), offered their viewpoints on patient and physician education in AAV. These expert comments are from the perspective of healthcare systems in the UK, the Netherlands, and Portugal; the views of AAV experts and patients in other European regions may differ.

Experts agreed that some key challenges exist, where more work is needed to improve patient and physician education across the board for AAV so that people are supported wherever they access care. Important gaps in knowledge and awareness around AAV were also identified for physicians, particularly non-specialist doctors and General Practitioners (GPs), underscoring key areas for improvement in overall medical education. In particular, all experts agreed that a significant opportunity exists to enhance shared care of AAV in everyday clinical practice and pinpointed key steps to achieving this

INTRODUCTION

AAV is a rare and severe multisystem disease affecting the small arteries.1,2 The condition is characterised by systemic inflammation across multiple body sites including the lungs, joints, kidneys, nerves, ears, and nose.1,2 Glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants form the cornerstone of current treatment approaches.1 Although AAV presents as an acute illness, the condition follows a relapsing, remitting course over many years.1 Patients are often poorly informed and shared decision-making is not widely performed. Over the course of their illness, patients may also interact with many different doctors, many of whom are not vasculitis specialists and whose knowledge of the disease’s causes and treatments may not be fully up-to-date.

This article captures the views of two key opinion leaders and two patient representatives on the subject of patient and physician education in AAV. Robson is a Consultant Rheumatologist in the UK; she leads a connective tissue disease and vasculitis clinical service and has a research interest in the development of patient-reported outcome measures in AAV and other forms of vasculitis, and into the psychological impact of rare rheumatic diseases. Ponte is a rheumatologist at the biggest academic hospital in Portugal, with responsibility for the vasculitis clinic, and is also a Clinical Investigator involved in rheumatology research. Verhoeven is Chairman of the Vasculitis Stichting (the Dutch Vasculitis Foundation) as well as the Chairman and Co-founder of Vasculitis International; his wife was diagnosed with AAV in 2002. Mills is a former dentist and patient with AAV; he founded Vasculitis UK with his wife, Susan, over 10 years ago and is also a Board Member and Co-founder of Vasculitis International.

PATIENT EDUCTION FOR PEOPLE WITH AAV

Are Patients with AAV Adequately Informed?

Once diagnosed with AAV, patients embark on a long journey of treatment with powerful immunosuppressant medications, often punctuated by periods of disease relapse and flare ups.1-3 Although treatment is typically overseen and orchestrated by a specialist centre, many patients will remain in the care of GPs and local consultants either before formal diagnosis or as part of ongoing monitoring and disease management over the course of a lifetime. Education for patients, carers, and physicians is the cornerstone of care optimisation but research indicates that important differences in perspective and priorities still exist, as well as key gaps in knowledge and understanding.2

On the question of whether patients with AAV are adequately informed about their disease and its management, both Mills and Verhoeven highlighted shortcomings in this area but conceded that time constraints in clinical practice are often at the root cause. “Doctors are busy people. They have 15 minutes to see a patient and they’ve got to do the diagnosis and plan the treatment in that 15 minutes,” noted Mills.

“It’s amazing how little patients understand and how little information they get in the hospital,” Verhoeven added, pointing to the results of a 2016 survey of Dutch patients with AAV carried out by Vasculitis Stichting, in which 41% of 532 respondents said they were not adequately informed about their disease, treatments, and the side effects of medications.4 “What we learned over time is that [patient advocacy groups] are in a better position to provide that sort of information than hospitals are in general. [Hospitals] have limited time and have a professional relationship with the patient, while [patient advocacy groups] have a more empathic, peer-to-peer relationship,” said Verhoeven.

Mills agreed that the paucity of patient education provided by physicians fuels the need for patient organisations to take up this crucial baton of informing and educating patients with ANCA vasculitis. “[Vasculitis UK’s] key objective is to plug the gap between professional understanding and patient understanding. It’s the basic philosophy that if you’re going to get good outcomes, patients have to understand their disease; they have to be knowledgeable about it and they need to get to grips with the treatment. Ideally it should be a matter of teamwork, the patient working with the professionals to deal with the problem and deal with the disease. Sometimes we achieve that extremely well, sometimes we don’t. We aim to work with the medical professionals rather than in parallel. Sometimes, I think patient organisations almost see the medics as being on the other side of the fence and their opponents.” He also cautioned that existing educational initiatives can sometimes create the impression that AAV is vasculitis, whereas, in reality, “it only represents 3 out of 18 types of vasculitis, all of which have renal involvement. However, AAV is more likely to be fatal if undetected or treated inappropriately.”

The importance of effective patient education was reiterated by Robson. “I find for an outpatient, just [for them] to have the time to ask all the questions…that have been building up is really important…otherwise people never feel like they get to the bottom of what’s going on. As a basic principle we’ve also found that it saves a lot of worry on the patient’s behalf…and also the aim is that it’s worth putting in a bit more resources at the beginning so that people don’t run into difficulties later on.”

Key Priorities for the Education of Patients with AAV

All four experts were broadly aligned when it came to the key knowledge that people with AAV need as they embark on their treatment journey, as Ponte affirmed: “Once we have a diagnosis, I usually sit down with them and talk about what the risks can manifest as, which organs the disease most commonly affects, red flags to be aware of [regarding relapse]…steroid side effects…the need for infection control [as infections can mimic disease symptoms] and vaccinations…and bone protection for high-dose steroid patients, etc.”

Robson elaborated: “There’s still a lot of mystery about vasculitis generally, so by the time patients get to see you in clinic or on the ward, they want someone to explain what AAV is to start with and what the cause is.” She also agreed that education on treatment plans, side effects, and long-term risks, particularly infection and cancer concerns, with long-term immunosuppression were important. “Obviously, it changes a bit in terms of what information they need as to what stage they are at. Often you give them an overview and then go back more into the chronic disease side of things after that initial treatment, particularly if they are really unwell. If they’ve been diagnosed and started treatment on the intensive therapy unit (ITU) then it’s very focused on what the treatment is at this stage. When you see patients back in clinic, you’ve got more time to go into the broader educational side of things.”

Robson noted that it was particularly important for patients to know how to decipher the differences between symptoms of the disease and treatment-related adverse events. Patients also require information on steroid side effects, in particular reassurances that these will improve as doses are tapered down, and education around ongoing disease management and dealing with issues such as fatigue. “Other key questions patients have are ‘how will this affect my personal and professional life,’ ‘will my strength be affected, my concentration and focus, sleep quality, infection risk, fatigue’?” expounded Ponte. “Also, if there are any habits or anything they can do themselves to improve or mitigate the disease in terms of food intake, physical activity, etc.”

From the patients’ perspective, Mills added that: “Professionals tend to measure success in terms of survival, whereas, once the immediate threat of death has passed, patients are more concerned about continuing quality of life…Chronic pain and mobility are usually big issues. Quality of sex life can be a major issue that nobody talks about, not just for men.”

Gaps in Patient Knowledge and Understanding

While there was consensus among the experts on the essential elements of patient education in AAV, there was evidence that more needs to be done to ensure key information is delivered and absorbed effectively. Verhoeven highlighted patients’ understanding of prescribed medication and a coherent strategy for managing the disease over the next 2–3 years as key gaps: “A lot of doctors in hospitals do not have a treatment plan, or at least do not share that plan with the patient, so it’s the relationship with the doctors more than the actual information…The first thing that patients should be told is which treatment track they will follow (cyclophosphamide or rituximab) and why; but the second question, ‘why,’ is almost never answered by doctors.” He explained that this has important implications for patients because rituximab involves frequent hospital visits for intravenous administration while cyclophosphamide may often be given as an oral tablet.

Mills concurred: “Doctors will tell them a treatment plan and what medication they’re on but don’t seem to go into any detail about it, in particular on monitoring. Patients don’t always realise that these are usually very potent drugs with quite significant side effects.”

However, Mills also acknowledged that the ANCA vasculitis therapeutic landscape is complex and beyond the understanding of most patients and that treatment decisions are often urgent and life-saving: “It’s getting the balance right with giving the information without scaring the patient,” he suggested. Another pressing question in patients’ minds is tapering of prednisolone, said Verhoeven. Data show glucocorticoid use carries significant emotional and social consequences, with many patients voicing concerns about both adverse effects and uncertainty around the dose-reduction processes.5

Continuity of Care

Verhoeven stressed that a key issue is not just the information that is imparted but the relationship and channels of communication between the patient and the treating physician. Lack of continuity of care, for example, poses a huge concern for patients. “The patient would like to see a particular doctor who he can cling to for the rest of his life while the hospital feels they only need to provide a doctor who is available at that point in time.” The medical community and patient organisations need to work together to solve this problem in the future, Verhoeven suggested. “For a patient this is a real issue because all of a sudden you lose your safety line, this one doctor that you can trust and rely upon. The impact of that on a patient is underestimated by most doctors.”

Mills agreed: “There’s not a lot of continuity of care. Once you’re on the track you’re probably seeing the registrar on rotation, so you might not ever see that doctor again. It’s a bit of potluck.” He noted that one of the core problems is the shortage of rheumatologists, in particular those specialising in vasculitis and rare autoimmune rheumatic diseases.

Robson noted that, although a team of doctors would typically be involved in disease management, having specialist nurses to provide more continuity of care is important because it’s not really feasible to have only one doctor who knows the patient. “Having a named nurse as well can help with this feeling that someone knows their case and can act appropriately,” she added.

Understanding the Optimal Approach to Patient Education

The style and approach of the treating physician are key elements for patients with AAV, who often endure persistent disease activity compounded by the adverse effects of long-term exposure to therapies and the psychosocial burden of serious ill health. Unsurprisingly, one-quarter of patients are estimated to suffer with depression, and anxiety affects >40%.6

Verhoeven commented that doctors tend to be most accessible during the first 6−12 months, when a patient is newly diagnosed and treatment is still being adjusted; however, their involvement then wanes over time. “But for patients this is a disease you suffer with lifelong…and it affects your day-to-day life.” He explained that doctors need the right level of empathy to recognise these long-term, ongoing problems and the burden they impose and to signpost patients to external sources of support and help such as patient organisations. “Ultimately, patients want doctors to be more aware of the everyday reality of living with AAV,” Verhoeven concluded. This stance is supported by research showing that patients with AAV consistently rate the psychological and social impacts of the disease higher than their physicians do.7 “Health is a lot more than just being physically okay and so doctors should look at the patient as a person rather than just treating the disease,”he added.

On the optimal approach to interacting with patients, Mills noted that: “Patients are like doctors, they come in all shapes and sizes with different levels of education. Some like to be told what to do and some have to be coaxed and cajoled into doing things.” He acknowledged that the patients who reach out to patient organisations tend to be more proactive and focused on maximising disease outcomes; hence, a whole layer of poorly informed patients may still remain, hidden below the surface. “There are a lot of people who are quite passive about it. They probably never find [Vasculitis UK] because they don’t go searching on the internet for things about vasculitis. Very often, these patients don’t even know what type of vasculitis they’ve got.”

From the clinician perspective, Ponte clarified that the decision to take a collaborative versus a more directive approach with her patients “depends on the type of disease and the individual personality of the patient. There are a lot of factors involved, like social factors and economic factors, that we also have to be aware of.”

Robson expanded on this point: “At the beginning, if a patient is very unwell and in the ITU, they are generally looking for someone to come in and be more didactic. But then when things are over that initial really acute phase, that’s when we really need proper educational sessions.”

Improving Shared Care Decision-Making in Clinical Practice

To improve shared care decision-making, Verhoeven stressed that it was essential for patients to have a direct involvement in multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, where the management of their disease is being considered. “It is important to develop access routes by which a patient who really feels in need can put themselves forward for discussion in this shared care, MDT Zoom session,” he explained.

Robson was also in favour of this approach: “If a patient is worried about something, it can be quite helpful to tell them that we’ve set aside some time to discuss things. It’s also good practice for doctors to have the facility to discuss complex cases with peers within rheumatology and other medical specialities to ensure the best outcomes for patients.”

Ponte noted that patients who are less well-educated tend to trust their doctors to take charge of the clinical decision-making. However, she will always take time to outline the treatment options and side effects. For individuals who are more invested, she also finds it helpful to discuss the underlying published evidence for their treatment approach. As part of shared care decision-making, it’s particularly important to give patients a choice on issues like speed of steroid tapering (risk of side effects versus flare) and drugs with fertility implications, she explained.

On patients’ current level of input into shared care decision-making, Robson conceded there is “definitely room for improvement” but flagged the importance of the timing of patient education. She agreed with Ponte that, because the optimal path for maintenance therapy is currently unclear, patients can have more of an input into clinical decisions based on a “weighing up” of individualised relapse risk versus the benefits of treatment withdrawal. More research is still needed to inform discussions about which maintenance approach would be optimal, Robson acknowledged.

MEDICAL EDUCATION FOR CLINICIANS

Priority Areas for Improving AAV Medical Education

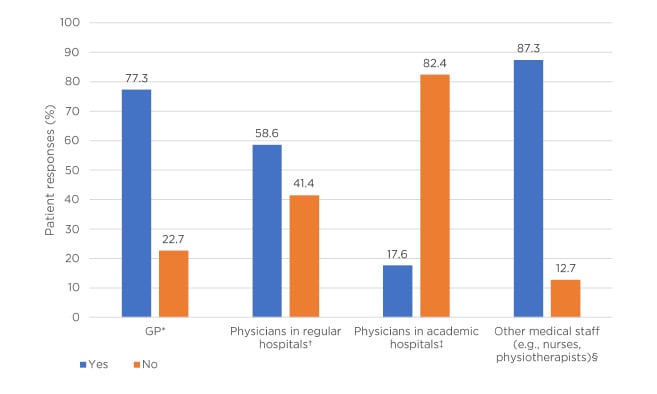

When seen through patients’ eyes, there is significant scope for improving medical education for physicians on AAV, particularly non-specialists and GPs, as highlighted by results from the Dutch survey of patients with vasculitis provided by Verhoeven (Figure 1).4 “Patients would prefer that their doctor really knew something about the disease that they’re being treated for,” expressed Mills. “It does happen in a consultation that doctors scoot behind the screen and they’re busy tapping into Google. They type in ‘vasculitis’ and try to do it learning on the hoof.” He continued: “Some patients are quite surprised that the consultant that they’re seeing, [be it a rheumatologist or nephrologist] actually doesn’t know that much about vasculitis. Then it dawns on the patients how rare vasculitis actually is.”

Figure 1: Patient responses to the question “Knowledge about vasculitis: indicate whether you are experiencing or have experienced it as a sticking point?”⁴

*The GP has too little knowledge about vasculitis (n=523).

†Medical specialists in regular hospitals have too little knowledge about vasculitis: the condition, treatment options, and aftercare (n=500).

‡Medical specialists in university hospitals have too little knowledge about vasculitis: the condition, treatment options, and aftercare (n=437).

§Other care providers have too little knowledge about vasculitis, e.g., the nurse, physiotherapist, and company doctor (n=502).

GP: general practitioner.

Verhoeven emphasised that training for less experienced, non-specialist doctors is key and can only be achieved using reliable resources that are easy to access and follow (e.g., he suggested the website, Understand AAV).8 He continued: “On our website in Holland, we have developed a 2-minute movie: ‘The 10 things about vasculitis everybody should know.’ We should also ask doctors the question: ‘how do you think your specialism could help?’” Verhoeven stressed that, ideally, medical education for doctors should feed down from the specialist centres. “Again, it’s the shared care concept so they can access an expert centre nearby in a formal setting and also develop training such as little videos and make sure they are easily accessible.”

Ponte agreed that medical education on AAV, particularly for non-specialists, could and should be enhanced. “Although guidelines clearly state that patients should be managed in close collaboration with, or at, a centre with specialist expertise…sometimes local physicians that don’t see vasculitis very frequently think they can manage it effectively and that is wrong,” she insisted.3 “Unfortunately, we have had some patients who were basically managed with steroids alone and developed very severe disease because nothing else was being done.”

GPs need to be aware that this disease needs to be treated and managed with the collaboration of physicians who have specific vasculitis experience and expertise, said Ponte. Even if management is taking place at the local level, communicating or liaising with specialist services in some way is crucial, especially because patients may often be unaware that their treating physician is not a vasculitis specialist. Both doctors also agreed that better education for GPs on recognising disease relapse is critical as such primary care doctors play a key role in flagging patients with AAV who might be undergoing a flare.

Asked about the key things that patients would like doctors to know about how the disease makes them feel, Verhoeven underscored the importance of adopting a more holistic approach. “The best way to deal with your disease is to deal with your health and that is an area we don’t focus enough on currently.” This stance is backed up by evidence showing that AAV exerts a significant impact on patients’ quality of life, affecting everyday function and employment; causing depression, anxiety, and fatigue; and compromising the ability to make future plans.1

Ponte concurred: “Sometimes we’re so obsessed with clinical outcomes [that] anxiety, depression, and other issues like that are sometimes neglected.”

The Importance of Multidisciplinary Team Collaboration

Verhoeven explained that he is involved in a 6 million EUR Dutch project called the Arthritis Research and Collaboration Hub (ARCH), where shared care decision-making is a central pillar. “I see this as a local hospital being in a shared care construction with an expert centre and, together, they have more knowledge and a better understanding of how to treat a particular case.” Verhoeven suggested that a key initiative to improved shared care decision-making could be fortnightly MDT video conference sessions with expert centres. “That would help the patient because that will increase his confidence in the way he’s being treated.” Better understanding and better acceptance of the treatment by patients will increase adherence to treatment and will lead to improved outcomes.

Both Ponte and Robson reaffirmed the importance of adopting a collaborative MDT approach to AAV, led by a rheumatologist but with involvement from other specialisms such as nephrologists and pulmonologists. “It’s good to have a range of opinions and insights from others and, as a doctor, to recognise your own limitations,” said Ponte.

Robson backed up this point: “We have a weekly MDT in our rheumatology department, and we also link in with other rheumatologists phoning in from other places. [We then] have specialists who we can contact, sometimes within the MDT but also beyond (e.g., ear, nose, and throat, and renal). We have a separate monthly respiratory MDT and clinic, and joint dermatology clinics. Most likely to be discussed at these meetings are inpatients on the ward, in ITU, or anyone failing standard first-line treatments, so particularly if they needed rituximab or a step up in treatment. It’s good to have regular peer-to-peer support.” This collaborative, discursive approach was also seen as important for junior doctors in training and other specialities. Providing smaller hospitals with the scope to link into larger, more specialist centres and share knowledge and expertise creates another key route to improved medical education, the experts agreed.

Education to Overcome Diagnostic Delays

AAV is a multisystem disease associated with a myriad potential signs and symptoms; this can make diagnosis difficult and specialist referral protracted for many patients. “You can’t teach GPs about all the rare diseases that exist, and a lot of AAV symptoms overlap with simple diseases,” said Verhoeven. Instead, he urged that ‘think systemic’ should be the key message for GPs or primary care physicians and local consultants. “If you see a patient with ear problems and he comes back with eye problems and later lung problems, don’t treat them as three individual cases but look at the whole picture and think systemic because he might be a patient with AAV.”

Mills expanded on this key point: “What we’d really like is for GPs to have a little awareness of these symptoms so that when they make a referral, they make a sensible referral. The problem is that AAV, in a very large proportion of cases, involves a skin rash. The chances are that patients will get referred to a dermatologist who will know very little about AAV. They can then languish with that dermatologist for years.” He continued: “It’s in the nature of medicine that doctors focus on the most obvious presenting symptom. Quite often, you have to prod and probe quite deeply into the medical history…to get the right answers. But you need to know the right questions to ask.” He suggested that artificial intelligence programs and machine-learning could be used to find patterns to help with diagnosis.

These issues were confirmed by Robson: “There can be a big delay to diagnosis. The problem is sometimes these presentations can look just like a normal infection. It’s the pattern recognition that’s a bit of a gap. If a patient’s come in and out with recurrent chest infections but also has ear, nose, and throat involvement and other systems involvement, it’s about someone stepping back and putting it all together. Sometimes it’s not completely obvious but sometimes you do think someone should have picked this up earlier.” She added: “To be fair though, by the time the rheumatologists have been called in, then it’s usually an easier diagnosis to make as the constellation of symptoms are more obvious by that point.”

Practical Steps for Improving Education

The key role of specialist centres in spearheading efforts to improve overall AAV medical education resonated with both patient and physician key opinion leaders. In particular, they emphasised the importance of information and knowledge ‘filtering down’ from expert centres to more grass-roots physicians. “If there are physicians who want to take care of these patients, they should receive some sort of training from academic centres, sit with physicians who see patients, and try to attend vasculitis seminars and workshops,” suggested Robson. “Things like grand rounds and local teaching and post-graduate teaching are important. More GP training, particularly, might be helpful. A big part of it is to keep trying to create opportunities to talk about [AAV] and how patients present.”

The experts also flagged the importance of clinical nurse specialists in improving education and smoothing the treatment journey for people with AAV. “Nurse specialists are a huge asset in any department treating patients with vasculitis. Patients get better outcomes when there’s a specialist nurse…because they have the time to explain things,” commented Mills.

Robson concurred: “We’ve got a specialist nurse who’s excellent at the medical side of the treatment but is also interested in the fatigue and the psychological side of things. It also gives patients the idea that they are being cared for as part of a team rather than just one particular doctor.” Nurse specialists also offer a friendly, recognisable face and important point of contact to help to guide patients as they navigate their treatment pathway, she added. They are also an important element in the overall continuity of patient care. Verhoeven strongly agreed with the important role played by clinical nurse specialists.

All experts agreed that physical resources remained of key importance in medical education for patients. “Something as simple as an information leaflet is enough to give patients an overview of vasculitis and how it is treated,” said Mills.

Ponte also emphasised the importance of physical resources to plug gaps in consultation times: “We are very limited with time in clinics and sometimes it can be hard. We have a website (Portuguese Society of Rheumatology [SPR])9 that explains vasculitis, which we can refer patients to, but leaflets are also important.”

This view was echoed by Robson: “We tend to print out Vasculitis UK materials to give to patients. They have been developed with patients but also with input from different clinicians so that the information is correct and with further links if people need it.” Consensus among the key opinion leaders was that helplines are also a valuable resource for informing and educating patients; examples include the helpline provided by Vasculitis UK and nurse practitioner helplines offered by individual hospitals. Another tool that could be helpful, Robson suggested, particularly in shared decision-making, would be visual aids that illustrate the various treatment pathways, with contextualising data on percentage of relapse, versus damage from disease or treatment, dependent on the treatment pathway chosen. Some of these data are not yet known or available to inform the creation of visual aids such as this, and this should be the focus of future research projects, she added.

Continuing on this point, Verhoeven outlined how patient associations can play a key role in the creation of tools such as short videos, website resources, and brochures. He pointed to two key recently developed websites, supported by Vifor, one targeted at healthcare professionals (HCPs) (Understand AAV)8 and one at patients and carers(My ANCA Vasculitis),10 which are available in multiple European languages. Vasculitis International11 is another important global initiative developed collaboratively by Verhoeven and Mills. This aims to support individual patient vasculitis groups and fuel their collaborative working. “This is now taking off because we can present ourselves as a truly European organisation,” noted Verhoeven. Earlier in 2021, in collaboration with HCPs and Vasculitis International members, Vifor also launched the AAV MasterClass, an interactive educational tool targeted at patients and carers.12

On the critical role of online education, Mills explained that Vasculitis UK have volunteered to fund the UK and Ireland Vasculitis Rare Disease Group (UKIVas)13 in setting up a professional medical education website for HCPs. The vision is to create a platform and landing site that becomes the ‘go-to place’ for HCPs seeking knowledge and information about vasculitis. “There isn’t any resource like that available at the moment,” said Mills, “and doctors don’t have time to trawl though and read papers on the subject; they need it to be there fast, simple, and accessible, pitched at ordinary doctor level not at specialists.” To further enhance medical education, Mills explained that UKIVas has recently collaborated with the Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) on a whole-day educational webinar on vasculitis for doctors. He stressed the importance of targeting such events towards ‘jobbing’ rheumatologists or nephrologists working at the district general hospital. “These are the people that really need to be educated because…they may see one or two cases of AAV in a year. That is where I think there is a big gap.”

Since this interview was conducted, Vasculitis UK, working with UKIVas, has taken the initial steps in developing a new easy-access website resource for all HCPs to aid in recognition, diagnosis, and treatment planning, especially for those with little knowledge or experience of vasculitis. “We have several other collaborative initiatives with UKIVas, all with the aim of improving outcomes,” explained Mills. “I view it all as a three-way interdependent partnership between patient, doctor/HCP, and pharma. We all need each other to survive.”

Group educational activities were also seen as key priories for building the knowledge base for both patients and physicians. For instance, Ponte described her participation in an interactive patient event organised by Vasculitis UK, where patients had the opportunity to hear about the latest clinical research and ask questions. “This was very positive…and also gave the chance for clinical investigators to recruit patients into trials and for patients to have an influence on the outcomes that are assessed in clinical research,” she noted. Other practical strategies for improving patient education include establishing patient support organisations and online groups; these can enable patients to share everyday experiences and concerns. “Above all, it is important that patients feel part of a community and recognise that they are not alone, especially as this is a rare disease,” Ponte concluded.

SUMMARY

These interviews reveal encouraging areas of common ground between patients and physicians on educational priorities for people with AAV and HCPs. However, they also highlight key areas for improvement in order to make the most important educational objectives a clinical reality across the board. By sharing insights and experience from both sides of the clinical divide, and increasing collaboration and shared care decision-making in practice, there is significant scope to improve the AAV journey for patients and optimise therapeutic outcomes from treatment.

Key Resources

Vasculitis International

Global initiative that aims to support individual patient vasculitis groups across Europe and fuel their collaborative working.

Understand AAV

Medical education website on AAV targeted toward HCPs.

My ANCA Vasculitis

Medical education website on AAV targeted towards patients and carers.

AAV Masterclass

Education learning platform, launched in collaboration with HCPs and Vasculitis International members, targeted towards patients and carers.

![EMJ Rheumatology 8 [Supplement 4] 2021 Feature Image](https://www.emjreviews.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/EMJ-Rheumatology-8-Supplement-4-2021-Feature-Image-940x563.jpg)