Meeting Summary

Patients with rheumatologic conditions, such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), often face being immunocompromised due to their disease state, or the immunosuppressive effect of their treatments. Managing immunocompromised rheumatologic patients can be challenging and complex.

This article reviews a GSK-sponsored Innovation Theatre session that took place during the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence 2023 Annual Meeting in San Diego, California, USA, on 14th November 2023.

Kevin Winthrop, Professor of Infectious Diseases at the School of Medicine at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU); and Professor of Public Health at OHSU-Portland State University (PSU) School of Public Health, Portland, Oregon, USA, provided insights into the immunocompromised patient within rheumatology. He considered the challenges of associated comorbidities, diagnosis, and implementing preventative measures.

Leonard Calabrese, Professor of Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University; Director of Clinical Immunology of the R.J. Fasenmyer Center; and Vice Chairman at the Department of Rheumatic & Immunologic Disease, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, USA, presented an interactive patient case overview of EGPA. He identified the need for practitioners to take ownership of patients with serious and opportunistic infections.

The session provided awareness of the origins of immunocompromised states, including disease pathophysiology and treatments. It also explained the increased risks of opportunistic infections among patients with rheumatological conditions, due to their disease and treatment. Additionally, it identified the need for holistic approaches in the management of those patients living with immunocompromising conditions.

Immunocompromised Patients In Rheumatology

Kevin Winthrop

Winthrop first provided an understanding of immunocompromised states in rheumatology, explaining that various diseases and therapeutic interventions contributed to immunodeficiency. Patients with RA on anti-TNF therapy or low-dose steroids, patients with psoriasis taking IL-23 inhibitors, and those with autoantibodies to interferon-γ receptor, will be immunocompromised. Winthrop emphasised the need for practitioners to consider and categorise patients based on their level of immunosuppression, as part of clinical decision-making.

Understanding Immunocompromised States

According to the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 2.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.4–2.9%) of the adult population in the USA, aged 18 years or older, may be immunocompromised due to a variety of conditions.1 These encompass autoimmune diseases such as rheumatic disease, neurologic disorders like multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, advanced or untreated HIV infection, active treatment for solid tumours and haematologic malignancies, or undergoing solid-organ and/or bone marrow transplants.2,3 The impact of these conditions can be amplified by their administered treatments.1-3 Winthrop highlighted the pivotal role of rheumatologists, amongst other specialists, who should be vigilant in “preventing infections in the face of immunosuppression.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies several immunosuppressive states, including primary immunodeficiencies, such as X-linked agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency, or chronic granulomatous disease. Winthrop acknowledged the rarity of these conditions, but highlighted their significant contribution to heightened risk. Secondary immunodeficiency can be induced by immunosuppressive drugs.4

Patients with multiple comorbidities may become immunosuppressed, rendering them unresponsive to vaccines and, thus, difficult to protect from infection, for example. Notably, a patient’s primary healthcare provider, in collaboration with other specialists, holds a pivotal role in assessing and determining the level of immune compromise, said Winthrop.

Rheumatological Diseases and Opportunistic Infections

Patients with rheumatological diseases such as EGPA, RA, and SLE may be immunocompromised as a result of their disease severity, associated comorbidities, and their use of immunomodulatory drugs.5 This can make them susceptible to opportunistic infections.

Rheumatological diseases can trigger alterations in innate immunity and neutrophil function, leading to immune defects that increase the susceptibility to infections. For instance, RA and other autoimmune diseases can induce neutropenia, particularly in severe disease states, and as a result of immunosuppressive treatments.5

Therapies and disease states can also diminish the adaptive T-cell response, where cell-mediated immunity is important for combating viruses and opportunistic infections such as fungal and mycobacterial infections. In conditions like RA, a reduction in clonal expansion and frequency of naïve T-cells in the periphery signify premature ageing of the immune system.5

Genetic factors also play a role, as indicated by data showing hypomethylation and overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in diseases like SLE, which contribute to oxidative stress, and increased susceptibility to infections like severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.6

Consequently, immunocompromised patients, which can include those with rheumatic diseases such as RA and SLE, have an increased risk of fungal, bacterial, and viral infections.7 This risk can be compounded by the use of immunosuppressive therapies.8

To characterise this risk, consensus recommendations have “redefined opportunistic infections as ‘indicator infections’,” said Winthrop. “Much like an indicator species, whose survival or presence signals some specific environmental condition or change, an indicator infection is the presence, or specific presentation, of a pathogen that suggests a higher likelihood of an alteration in host immunity” [specific to immunomodulation by a biologic or other immunosuppressive therapy], as according to Winthrop et al.9

Winthrop stated that these infections serve as indicators of disruption to the immune milieu. As such, this should prompt practitioners to reassess their patients, and adjust their management accordingly.

Incidence of Mycobacterial Infections

Winthrop detailed several examples of opportunistic infections, focusing on the incidence of mycobacterial infections such as tuberculosis (TB) and non-tuberculous mycobacterium (NTM). These infections are over-represented in those with compromised immune states, particularly among individuals treated with biologic anti-TNF therapies. Winthrop highlighted an underlying immunodeficiency, with rates of active TB being five- to tenfold higher than background rates, particularly in regions with higher prevalence. In Europe and North America, NTM incidence ranges from 40–74 infections per 100,000 patient-years,9-11 while in Asia, it is 230.7 infections per 100,000 patient-years.9,12

Winthrop also explained that age-related immune system impairment, compounded by disease and therapy, increases the risk of opportunistic infections. A study using automated pharmacy records from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, USA, identified patients with inflammatory disease exposed to anti-TNF therapy (N=8,418).10 The crude background incidence rates of TB and NTM in the general population were low, at 2.8 (95% CI: 2.6–3.0) and 4.1 (95% CI: 3.9–4.4) per 100,000 person-years, respectively.10 This increased to 5.2 (95% CI: 4.7–5.8) and 11.8 (95% CI: 11.1–12.6) per 100,000 person-years, respectively, in those aged 50 years and older.10 Notably, in those with RA unexposed to anti-TNF, the incidence rate of TB and NTM was 8.7 (95% CI: 5.3–13.2) and 19.2 (95% CI: 14.2–25.0) per 100,000 person-years, respectively, whereas those exposed to anti-TNF therapy increased to 56 (95% CI: 24.0–111.0) and 105 (95% CI: 59.0–173.0) per 100,000 person-years, respectively.10

Moreover, Winthrop outlined that disease state, alongside therapies such as high-dose steroids, impacts the risk of opportunistic infection and latent virus reactivation rates. For instance, cytomegalovirus is more common in those with polymyositis/dermatomyositis and SLE than in those with Sjögren syndrome or RA.7 A retrospective cohort study using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database from 2000–2013 (N=76,966), identified an increased incidence of candidiasis, TB, salmonellosis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes zoster (HZ) in patients with SLE and RA, compared to other diseases.7 Multivariable Cox analysis revealed that, relative to SLE, polymyositis/dermatomyositis was associated with a significantly higher risk of opportunistic infections (hazard ratio: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.08–1.29).7

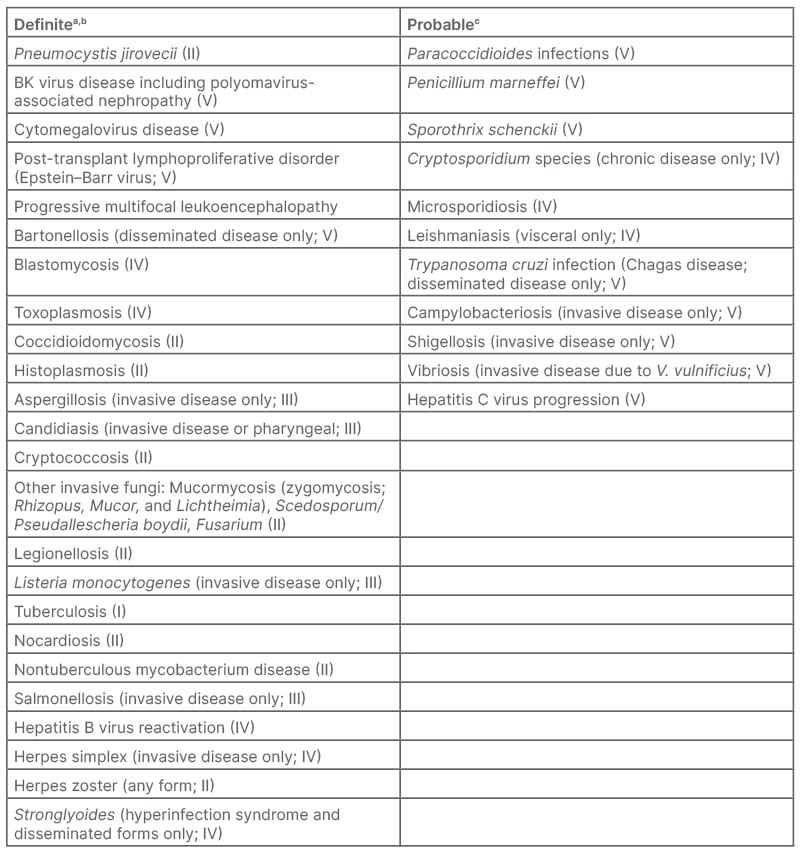

To help prioritise key pathogens as clinically important opportunistic ‘indicator’ infections, a list of recommended pathogens and presentations have been proposed. This can help healthcare professionals to consider the immunocompromising effects of biologic therapies, and the associated risk of opportunistic infections (Table 1).9

Table 1: Pathogens and/or presentations of specific pathogens to be considered as opportunistic (or ‘indicator’) infections in the setting of biologic therapy (level of evidence I–V).9

A) Generally do not occur in the absence of immunosuppression, and whose presence suggests a severe alteration in host immunity; B) Can occur in patients without recognised forms of immunosuppression, but whose presence indicates a potential or likely alteration in host immunity; C)

Published data are currently lacking, but expert opinion believes that risk is likely elevated in the setting of biologic therapy.

Taken from Winthrop et al.9

Winthrop also highlighted that while not all indicator infections are ‘serious’, i.e., necessitating hospitalisation or parenteral therapy, infections like TB can have significant implications, both for the individual and for public health authorities. Others, such as HZ and most Candida, can lead to therapy interruption and, therefore, be “quite a nuisance” to patients and lead to therapy interruption, he added.

Impact of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Rheumatology: The Herpes Zoster (Shingles) Example

Winthrop proceeded to consider the role of vaccine-preventable diseases in rheumatology using HZ as an example. In those who are immunocompromised, there is an increased risk of HZ, which causes shingles, and associated complications.13 This infection can pose a significant additional health burden on individuals with rheumatic disease.13-15

Exposure to varicella zoster virus (VZV) primarily occurs through chickenpox infection.16 Anyone previously infected with, or vaccinated against, VZV is susceptible to developing HZ.16,17

Following primary VZV infection (chickenpox), the virus becomes latent in the dorsal root and cranial nerve ganglia, and can reactivate later to cause shingles.16

In the USA, approximately one in three people will develop HZ or shingles in their lifetime.16 Moreover, around 99.5% of adults born before 1980 in the USA are at risk of developing HZ, due to prior VZV infection.16

HZ is characterised by a painful blistering rash affecting one or two adjacent dermatomes,18 typically lasting 7–10 days, with skin healing within approximately 2–4 weeks.19

The degree of disease burden and risk of complications are increased in individuals who are immunocompromised. In a population-based retrospective study of over 4 million, complications of HZ were more than twice (2.37 times [95% CI: 2.01–2.80]) as likely in those who were immunocompromised than in those who were not.20

Winthrop noted that while it may seem a non-serious infection, HZ can lead to systemic and neurological manifestations. These atypical HZ cases are more likely to be multi-dermatomal, disseminated cutaneous,18,21 and severe, with prolonged duration.18 This can also result in invasive complications, such as hepatitis, encephalitis, and pneumonitis,16,18,22 and an increased short-term risk for stroke.23

Impact of Age and Autoimmune Disease on Herpes Zoster (HZ)

Age and the presence of autoimmune disease are key risk factors for HZ. Similar to healthy individuals, the risk of HZ increases with age in those with autoimmune conditions, such as SLE, RA, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis.24 The risk of developing HZ in patients with autoimmune conditions was approximately 1.5- to twofold higher than in healthy individuals.24

In individuals with RA, the adjusted incidence rate of HZ in adults aged ≥18 years was approximately 1.93 times (95% CI: 1.87–1.99) higher when compared to those without RA.25 In those living with SLE, despite typically being younger than those with other rheumatological diseases, therapies and diminished T-cell function increase the risk of HZ, with an incidence rate of 15.19 (95% CI: 14.69–15.69) per 1,000 person-years compared to 4.82 (95% CI: 4.81–4.84) per 1,000 person-years in those without SLE.26 Additionally, patients with SLE treated with immunosuppressants are about 1.5 times (incidence rate ratio: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.36–1.56) more likely to develop HZ than those not treated with an immunosuppresant.26

More than 9 million adults in the USA face an increased risk for HZ reactivation due to conditions like RA, and psoriasis and/or their associated therapies, and underlying immunocompromising conditions.27-30

Considerations for Managing Herpes Zoster in Patients with Rheumatic Diseases

Winthrop concluded by explaining how healthcare professionals should manage the risk of HZ reactivation and shingles in patients with rheumatic diseases. He noted the CDC and ACR guidelines recommend prevention through vaccination.31,32 He also suggested preventing complications through managing comorbidities, and steering individuals away from immunosuppression and immune system modulation, and towards lower-risk therapies.

Overview of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis Disease

Leonard Calabrese

EGPA, previously known as Churg–Strauss syndrome, is a rare, multisystemic, immune-mediated inflammatory vasculitis,33 often associated to a history of asthma and/or allergies.33,34 Calabrese highlighted that due to the complexity of care and the condition’s varied characteristics, many affected individuals go undetected. Underdiagnosis contributes to making it one of the rarest forms of vasculitis,35 with an estimated annual incidence of 0.5–4.2 cases per million people per year.33,34 It affects both males and females equally.34-36

Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

The precise cause of EGPA is not fully understood, but it typically manifests in three phases: prodromal asthma, history of allergic rhinitis, and sinusitis, which can be complicated, as people will often have both asthma and nasal polyps;33-35 eosinophilic characterised by eosinophil infiltration;33-34 and small-vessel vasculitis.33-34

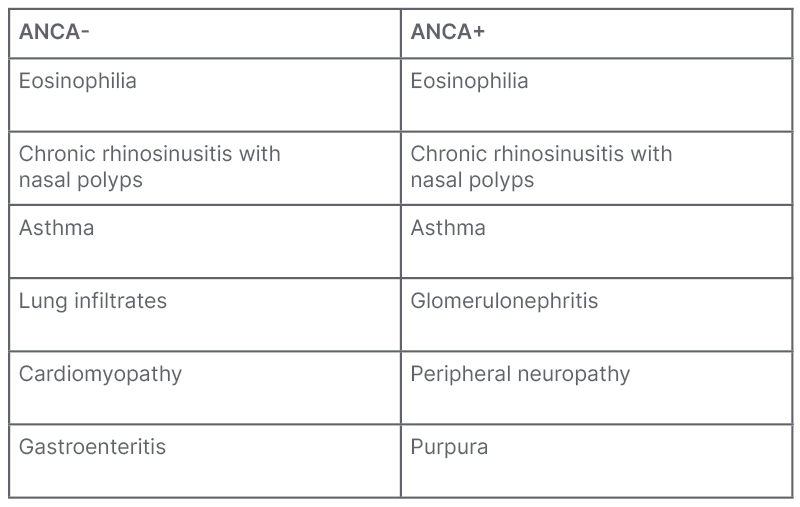

However, these characteristics may not always be evident or obvious. Calabrese stated that the clinical presentation is not sequential, and can be insidious and diverse (Table 2). EGPA can also impact multiple end organs.33-35

Table 2: Main clinical characteristics of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis based on ANCA status.34

Adapted from Emmi et al.34

ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

The phenotype of EGPA is heterogeneous, ranging from mild to life-threatening symptoms, making diagnosis and classification challenging.33-35 While classification criteria for diagnosis have been proposed, they remain unvalidated.34 Relapse in EGPA is also common.37,38

Around 40% of patients with EGPA test positive for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA),39 and those who are ANCA-positive often have vasculitis complications, such as peripheral neuropathy, glomerulonephritis, and purpura.33,34 Conversely, the majority of those with EGPA are ANCA-negative, and exhibit eosinophilic disease features like cardiomyopathy, gastroenteritis, asthma, and lung infiltrates.33,34

Calabrese noted that genome-wide association studies indicate that patients who are ANCA-positive share risk alleles for neuropsychiatric lupus, while no genetic association was found in ANCA-negative EGPA cases. Grouping these conditions together, then, may not be appropriate.

Immunocompromised State in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Calabrese reiterated the possible relationship between HZ, vasculitis, and vis-à-vis the use of immunomodulatory therapy.

Several studies support the notion that patients with EGPA and immunosuppressive therapies are associated with an increased risk of infection.34,35,40

Calabrese noted the vulnerability of patients to the complications of HZ when exposed to B-cell depleting agents, alkylating agents, and high-dose glucocorticoids. Vasculitis is noted as one of the potential complications/risks of HZ,41 with studies indicating an association between VZV, a previous HZ infection, and the development of certain types of vasculitis.41-44

A study examining 132 patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (including 17 cases of HZ), over a mean follow-up of 140 months, demonstrated that up to 82% of opportunistic infections occurred whilst on immunosuppressive therapy.45

Calabrese prompted the audience to consider monitoring for opportunistic or serious infections in similar patients, emphasising the implications of selecting treatments, in accordance with guidelines, that have a relative risk for these individuals. Calabrese presented examples of noteworthy infections, including complex urinary tract infection (Escherichia coli), pneumonia (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), fungal pneumonia such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia/pneumocystis pneumonia (Pneumocystis jirovecii), TB (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and HZ (VZV).

Treatment Recommendations for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

The ACR and European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) have published recommendations for the treatment of EGPA,40,46 which requires ongoing medical care due to its relapsing and remitting nature.

Traditionally, EGPA treatment, across all severities, has centred on high-dose corticosteroids.40,46 In severe cases involving vasculitis, cardiac, gastrointestinal, motor neuropathy, and nephritis, additional immunosuppressants are incorporated.40,46 These drugs constitute the standard of care for EGPA; however, long-term use poses the risk of complications or toxicity.33-35,40

Rheumatologic Patient Case Study Overview

Leonard Calabrese

Calabrese presented a case study of a 53-year-old White male, previously diagnosed with moderate persistent adult-onset asthma, who presented to allergists/pulmonologists 6 years previously with a cough, shortness of breath, and airway obstruction, noted on pulmonary function tests. Patchy ground-glass opacities observed on a CT scan raised the suspicion of eosinophilic pneumonia. Additionally, 2 years prior, the patient underwent a polypectomy for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, and has since been managed with chronic nasal corticosteroids.The patient was prescribed a high-dose combination inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist inhaler, taken twice daily, along with a chronic nasal corticosteroid, also taken twice daily. Calabrese noted that this medical history may not have triggered immediate concern for a referral.

Note: this case may not be representative of all patients.

Pertinent Past Medical History

Reflecting on the medical history of the patient case, Calabrese noted that alongside asthma and rhinosinusitis, the patient presented with malaise, unintentional weight loss, fatigue, arthralgias, and numbness/tingling in the feet without motor symptoms. In a vasculitis clinical setting, Calabrese noted that new-onset neuropathy with eosinophilia typically indicates EGPA axiomatically.

The diagnostic findings identified an elevated absolute eosinophil count (white blood cell count of 15,000/mm3 and absolute eosinophil count of 1,200 [8% eosinophils]). Electromyography indicated mild axon loss, and mild sensory polyneuropathy. The patient tested negative for ANCA and rheumatic factor, with a Five-Factor Score of zero (mild-to-moderate).

The patient case was diagnosed with mild-to-moderate EGPA 6 months ago, and has since been under rheumatologic care, with ongoing monitoring by a pulmonologist and otolaryngologist.

Consequently, the patient case commenced high-dose glucocorticoid induction therapy at 1 mg/kg, tapered to 20 mg once daily over 3 months, and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug to be taken as needed. While joint pain and breathing improved, attempts to taper were hindered due to joint pain flares and respiratory distress.

Recent Medical History and Current Clinical Visit

Three months ago, the patient presented to the emergency department with new-onset fever (100.4 °F/ 38 °C), chills, productive cough with coloured sputum, and shortness of breath. The patient was hospitalised for 3 days and, based on a CT image showing non-segmental consolidation with air bronchograms suggestive of alveolar pneumonia, was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia. Due to their previous medical history of asthma and reactive airways, the patient was treated with antibiotics, and continued on maintenance corticosteroids.

EGPA and the administration of high-dose glucocorticoids placed the patient in an immunocompromised state.

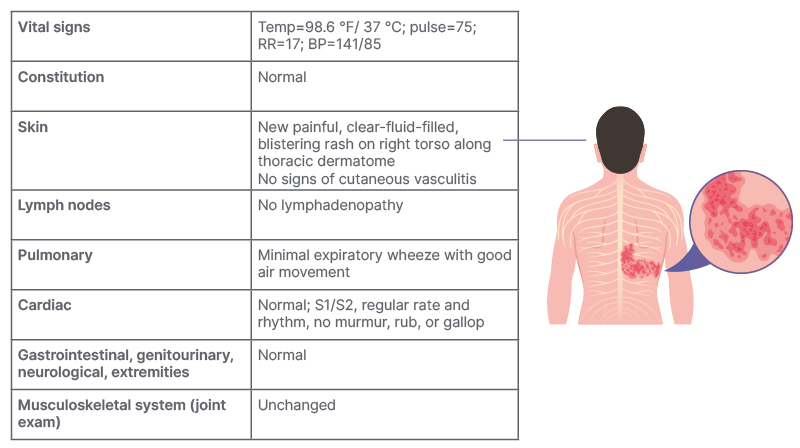

Fast-forward to the present day, the patient visited a rheumatologist presenting with a new, intensely painful, burning erythematous blistering rash on the torso (Table 3). Additionally, the patient reported weight gain over the previous 6 months, insomnia, and emotional lability.

Table 3: Patient case study overview – Current clinical visit and patient complaints.

Note example may not be representative of all patients.

BP: blood pressure; RR: respiratory rate; Temp: temperature.

This case outlines the importance of early detection and management of EGPA, not only for controlling disease activity, but also for acknowledging the increased susceptibility to infections such as HZ, due to the induced immunocompromised state. The administration of high-dose glucocorticoids left the patient vulnerable to opportunistic infections. This case serves as an example, highlighting the importance of monitoring patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, and emphasising the importance of promptly identifying opportunistic infections.

Discussion on an Holistic Approach to the Care of the Immunocompromised Rheumatologic Patient

Kevin Winthrop and Leonard Calabrese

The complexity of identifying an immunocompromised patient in rheumatology poses several challenges. Once identified, the subsequent steps in their treatment and care become pivotal in terms of therapeutic consideration and the complications that may arise, such as opportunistic infection.

Winthrop highlighted the importance of considering initial strategies in managing high-risk therapies and diseases. For instance, he noted the heightened risk associated with long-term high-dose glucocorticoid use (>10 mg), emphasising the increased susceptibility to bacterial infections such as urinary tract infections, community-acquired pneumonia, and disseminated Mycobacterium avium. His recommendation underscored the necessity of tapering patients off steroids, or at least minimising dosage.

Moreover, Winthrop considered insights into the heightened risks associated with therapies, such as those that inhibit the Janus kinase pathway, the reactivation of HZ, and recurrence of shingles. He also noted similar infection risks with anti-TNF, anti-IL-17, and B cell depletion therapy, although he stated infection risk was minimal with anti-IL-23 and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the context of ankylosing spondylitis. Winthrop suggested working with rheumatologists to tailor treatments based on identified risks.

Calabrese highlighted the importance of the standard of care in using proactive monitoring of patients undergoing high-dose immunosuppression for globulin levels, especially those on B-cell depletion therapy or glucocorticoids.

Winthrop further emphasised the challenges in screening for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in immunosuppressed patients. False negatives and false positives in testing necessitate repeated assessment (two to three times) before a confident diagnosis. Additionally, he recommended considering multiple approaches, such as a skin test 3–5 days prior, to increase the sensitivity of, for example, the interferon-γ release assay test.

Finally, the discussion considered the uncertainties surrounding the risk of developing shingles in younger people who had been vaccinated against VZV, but with no primary exposure, with Winthrop indicating that more data was needed.

Adopting a holistic approach to patient management is imperative. Calabrese noted the pivotal role of interprofessional care in managing immunocompromised patients.

Educating patients on the risk of serious or opportunistic infections, enabling informed decision-making, and fostering collaboration among primary care providers and specialists, is crucial for comprehensive care pathways.

The discussion underscored the importance of a holistic approach in managing immunocompromised rheumatologic patients, emphasising not only therapeutic considerations and complications, but also the collaborative nature required for optimal patient care.

SUMMARY

There is a heightened susceptibility of immunocompromised patients with rheumatic diseases to fungal, bacterial, and viral infections, including HZ,7 and this is further amplified by immunosuppressive therapies.8

To counter these risks, the CDC and ACR have recommended preventative measures against vaccine-preventable diseases and related complications in adults who are, or will be, immunocompromised due to their underlying disease or therapy.31,32

Emphasising a holistic patient management approach, this session underscored the necessity of considering the increased risk of preventable diseases and infection in immunocompromised rheumatic disease patients, and the subsequent preventable burden it imposes on a patient’s health.