Author: Theo Wolf, Senior Editorial Assistant

![]()

At this year’s European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) Congress, taking place on 1st–4th June, Jacob van Laar, Professor of Rheumatology, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, provided insights into strategies to manage patients with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis.

DIFFICULT-TO-TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS: A CASE

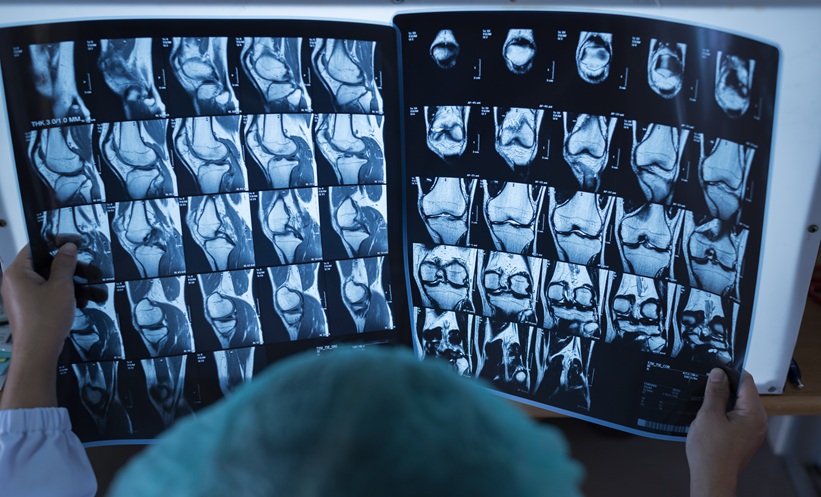

Van Laar began by discussing the case of a 60-year-old female with obesity who was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis 15 years earlier. The patient had cycled through the common conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD), including many of the biologic DMARDs as well. Her medical history also included deep vein thrombosis, debridement of the right knee because of a torn meniscus, total knee replacement on the right side, and ischaemic heart disease. The patient’s current symptoms included fatigue; morning stiffness lasting 2 hours; and pain in the hands, feet, wrists, shoulders, and elbows. She was taking prednisolone as monotherapy (7.5 mg), and had started taking celecoxib (200 mg twice daily). However, this combination of treatments was not sufficient to reach low disease activity.

On physical examination, the patient had a BMI of 32, and skin atrophy with haematomas. Rheumatological investigation revealed synovitis in both wrists. Laboratory findings demonstrated an acute-phase response, and confirmed that the patient was double positive for rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides. Van Laar also noted that the patient always had some disease activity, sometimes severe and sometimes moderate, despite all kinds of treatments, and had failed multiple conventional and biological DMARDS.

DEFINING DIFFICULT-TO-TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

The definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis consists of three criteria agreed upon by a multidisciplinary group of experts. According to van Laar: “It’s in a way an arbitrary definition, but it will help us in future clinical trials to define this subgroup.” The first criterion is failure to respond to two biological or targeted synthetic (b/ts) DMARDs with different mechanisms of action, after failing conventional DMARD therapy. The second criterion is presence of signs suggestive of active or progressive disease, defined as one or more of the following items: at least moderate disease activity; signs or symptoms suggestive of active disease; inability to taper prednisolone below 7.5 mg; rapid radiographic progression; and rheumatoid arthritis symptoms that are causing a reduction in quality of life. “Not unimportantly, we also felt that of course the patients and the treating physicians should have a stake in labelling a patient as difficult to treat,” added van Laar. Therefore, the third criterion is that the management of symptoms should be perceived as problematic by the rheumatologist or the patient. Using this definition, the proportion of patients meeting the criteria for difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis will range from 5% to 20%. “I think we’ve kind of overlooked this population because we are focused so much on treating patients very early,” summarised van Laar.

MANAGEMENT OF DIFFICULT-TO-TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Van Laar spoke about points to consider for the management of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. If a patient has a presumed diagnosis of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis, the possibility of misdiagnosis or the presence of a coexistent mimicking disease should be considered as a first step. “I still see, once in a while, patients referred to me with difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis who don’t have difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis, but for example crystal arthropathy, which can also be polyarticular,” revealed van Laar. Secondly, when there is doubt on the presence of inflammatory activity based on clinical assessment and composite indices, an ultrasound may be considered. It is also important that composite indices and clinical evaluation are interpreted with caution in the presence of comorbidities, especially obesity and fibromyalgia, because these may directly heighten inflammatory activity, or overestimate disease activity.

“We need to involve the patient,” said van Laar. For this reason, treatment adherence should be discussed and optimised within the process of shared decision making. After failure of a second or subsequent b/tsDMARD, and particularly after two TNF inhibitor failures, treatment with a b/tsDMARD with a different target should be considered. If a third or subsequent b/tsDMARD is being considered, the maximum dose, as found effective and safe in appropriate testing, should be used. “It’s understandable that in these patients, you are more cautious in prescribing the optimal dose, but […] if there’s no contraindications, for example in terms of kidney function, go for the optimal, high dose,” van Laar commented.

Comorbidities that impact quality of life, either independently or by limiting rheumatoid arthritis treatment options, should be carefully considered and managed. In patients with concomitant hepatitis B or hepatitis C viral infection, b/tsDMARDs can be used, and concomitant antiviral prophylaxis or treatment should be considered in close collaboration with hepatologists. “I think the management of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis patients increasingly depends on close collaboration with other specialities, including the lung specialist, gastroenterologist, nephrologist, or infectious disease expert,” emphasised van Laar. In addition to pharmacological treatment, nonpharmacological interventions should be considered to optimise management of functional disability, pain, and fatigue. “Again, the level of evidence is relatively low, like for the other points, but the level of agreement for all these points was very high,” stated van Laar.

Appropriate education and support should be offered to patients to directly inform their choices of treatment goals and management. Rheumatologists should also consider offering self-management programmes, relevant education, and psychological interventions to optimise a patient’s ability to manage their disease confidently.

DIFFICULT-TO-TREAT RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS: A CASE

To finish, van Laar returned to the patient case he presented in the beginning. Although the criteria were not available at the time, this patient fulfilled the definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. According to van Laar, the key strategic decision was to invest time in the patient.

Initially, the issue of prednisolone was discussed, which the patient had had been using as an analgesic, upping the dose when they were in more pain. “The key thing is not to change the dose from what you have been prescribed,” explained van Laar. He added: “This lady had gained a lot of weight from prednisolone; I think 20 kg. She wasn’t obese before she had rheumatoid arthritis.” Later on, it may be possible to taper the dose.

Secondly, van Laar and his team convinced the patient that methotrexate was the anchor drug for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. This was necessary because the patient had developed nausea from methotrexate, and was reluctant to take it again. The patient was started on the lowest dose of 2.5 mg per week, and reassured that this would not be associated with any side effects. Van Laar described this as the placebo effect of the doctor. Over time, the dose of methotrexate was slowly increased to the highest tolerable dose. Ultimately, the patient was able to tolerate 10 mg per week, which van Laar was “quite happy with” and considered to be a “nice background dose.” Finally, one of the new JAK inhibitors was introduced.

Within 2–3 months, the patient had achieved a state of low disease activity, and was able to return to work and exercise. “Having an overall look at the patient will help you improve the management,” summarised van Laar.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, van Laar shared three take home messages: difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis, as defined by the EULAR task force, is not uncommon; the management of patients with difficult-to-treat disease requires an holistic approach; and the condition is not necessarily endstage or irreversible.