BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Despite technical advances in investigations and treatment, the 5-year survival for lung cancer (LC) remains poor. Studies suggest that continued smoking after a diagnosis of LC independently worsens quality of life and shortens life expectancy; however, these were small, retrospective cohorts where smoking was usually only self-reported and only recorded at baseline. The authors have recently shown that quitting smoking following a diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) may lead to a reduction in mortality by 17% at 1 year.1

Smoking can adversely affect outcome by causing and accelerating other illnesses in people with LC. Smokers are more likely to be diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, thrombosis, and many other conditions.2,3 Continued smoking worsens any comorbid condition, which can lead to increased risk of infections, resulting in delays or interruptions to LC treatment.

In patients with head and neck cancer, those who stopped smoking following diagnosis survived twice as long as those who continued to smoke. Those who continued to smoke had a four-times greater rate of recurrence.4 In patients with breast cancer, recurrence in smokers was 15% higher (p=0.039) compared to those who quit.5 This is further replicated in patients with prostate cancer.6

The aim of the study was to determine if quitting smoking after a diagnosis of LC reduces complication rates, including treatment interruptions and hospital admission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As part of a UK multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study of 1,134 patients with newly diagnosed NSCLC, the authors recorded self-reported smoking status, validated with exhaled carbon monoxide readings, at baseline and each follow-up visit until death for up to 2 years. Treatment complications were noted by free text if reported by the patient (e.g., diarrhoea, vomiting), or by the clinical team (e.g., post-operative wound infection, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, radiation pneumonitis). They were reviewed by a study clinician blinded to smoking status but were not graded according to severity.

Smoking cessation treatments were offered according to local services. Data were recorded on study case report forms and confirmed from hospital records and cancer databases; data were analysed with Stata.

RESULTS

Of the 1,134 patients recruited, 290 (25.6%) were smokers at baseline and 84 (29%) of these quit within 3 months of diagnosis. Continued smokers (66.5 years; standard deviation: 9.4) were of similar age to quitters (66.1 years; standard deviation: 9.6; p=0.232), but 34.7% of quitters had Stage I and II NSCLC, compared to 19.2% of smokers (p<0.001). 28.6% underwent surgery compared to 8.1% in those who continued to smoke (p<0.001). At 12 months, 55.6% of quitters were deceased compared to 68.1% of continued smokers (p<0.01).

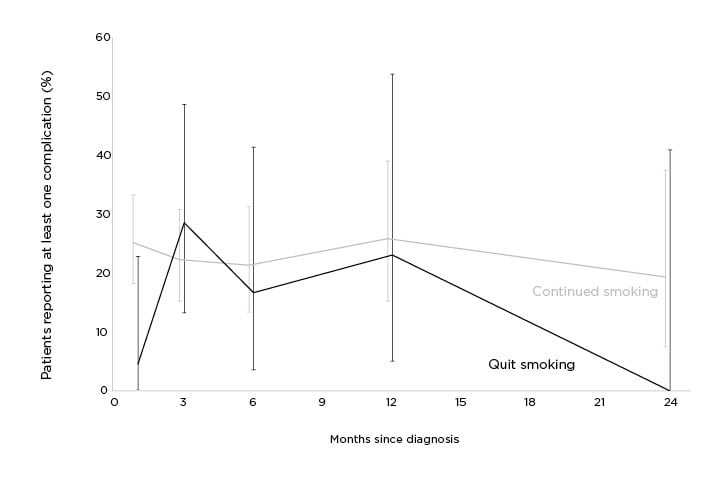

At 1 month, quitters had fewer treatment complications than those who continued to smoke (p=0.03). At 6 months (p=0.76) and 12 months (p=1.00), there were no differences in complication rates between quitters and continued smokers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Non-small cell lung cancer treatment complication rates comparison by smoking status.

CONCLUSION

Quitting smoking after a diagnosis of NSCLC is associated with fewer treatment complications at Month 1. This may be due to the confounding effects of increased Stage I and II tumours and higher number of surgical resections in quitters. The authors have continued to follow outcomes with larger numbers, grouping treatment-related complications into ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, or ‘severe’ according to standard definitions, as well as noting whether these complications necessitated treatment delays or treatment changes.