BACKGROUND

Sarcoidosis and tuberculosis (TB) share similar clinical, histological, and radiographical characteristics, and can be difficult to differentiate.1 Early recognition and diagnosis of TB is imperative, as treatment modalities differ substantially. Similarly, immunosuppression in patients with sarcoidosis can be catastrophic in patients infected with TB.1,2 The authors present a case of biopsy-proven sarcoidosis with subsequent development of multi-organ system failure secondary to disseminated TB.

CASE PRESENTATION

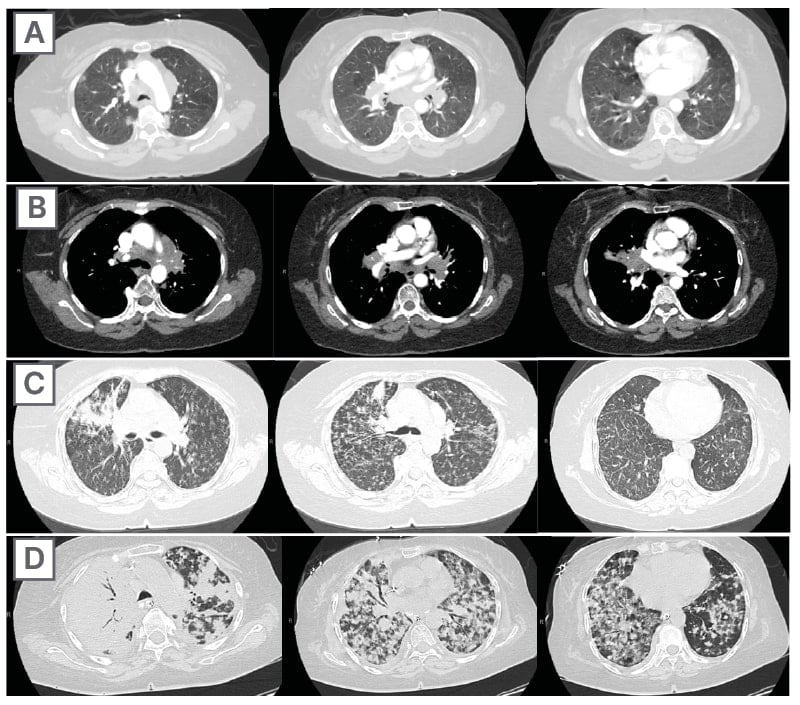

A 58-year-old female with recently diagnosed COVID-19 pneumonia was found to have a dry cough and dyspnoea in the setting of persistent bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy associated with bilateral nodular infiltrates. Of note, she immigrated to the USA from India 10 years prior, with the most recent travel to India 2 years ago. Quantiferon testing upon return to the USA was negative at that time. Workup included bronchoscopy with endobronchial ultrasound revealing non-caseating granulomas with negative stains for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). She was diagnosed with Stage 3 sarcoidosis and initiated on prolonged steroid taper with improvement of symptoms. With taper of steroid dose, however, she developed lymphocyte-predominant exudative effusion with negative cultures, and was reinitiated on a protracted steroid course with rapid symptom resolution. At 4-month follow-up, she had worsening CT findings upon steroid taper, and was started on azathioprine. One month later, she required hospital admission for worsening dyspnoea and fatigue. She was noted to be febrile, tachycardic, and tachypnoeic with worsening hypoxia. Subsequent CT chest showed progression of bilateral nodular infiltrates with new right upper lobe consolidation and air bronchograms concerning for multifocal pneumonia (Figure 1). Incidentally, she was also noted to have calcified splenic granulomas. She developed rapid clinical deterioration, ultimately requiring mechanical ventilation, pressor support, and continuous renal replacement therapy. Repeat bronchoscopy revealed diffuse alveolar haemorrhage with multiple AFB smears positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was immediately initiated on quadruple therapy, but unfortunately, despite treatment, developed refractory shock and passed away 2 weeks after initial presentation.

Figure 1: CT progression of patient’s sarcoidosis and tuberculosis.

A) Initial adenopathy with peripheral patchy ground glass opacities in the right lung following COVID-19 pneumonia. B) Persistent bulky adenopathy 1 year after initial presentation. C) Extensive nodularity throughout the right lung with increasing confluent opacities in the right upper lobe and stable mediastinal lymphadenopathy 2 years after initial presentation. D) Tuberculosis superimposed on sarcoidosis with progression of nodular infiltrates, worsening right upper lobe consolidation, and air bronchograms with incidental calcified splenic granulomas (not pictured).

CONCLUSION

TB and sarcoidosis share synonymous manifestations, making differentiating between progression of sarcoidosis and the development of TB difficult, especially in patients who have biopsy-proven sarcoidosis. This patient’s initial negative Quantiferon testing and AFB stains, CT scan findings, pathology, and rapid symptom resolution with steroids support the initial diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Given her history and no recent identifiable risk factors, TB was lower on the differential at initial presentation to the hospital. While findings of lymphocyte-predominant pleural effusions3 and splenic granulomas may be seen with sarcoidosis, this should raise suspicion for tuberculosis and prompt further investigation. This case highlights diagnostic challenges and the need to keep TB on the differential in patients with previous risk factors, despite negative testing and progressive CT findings with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis.