BACKGROUND

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is a rare, potentially fatal lung condition. It can vary in presentation and severity, but classically presents as an acute, febrile respiratory illness that is rapidly progressive. The pathophysiology of this disease is poorly understood. Diagnosing AEP relies on an extensive review of clinical history, data, imaging, and physical examination. The severity of illness highlights the importance of understanding its triggers, risk factors, and mechanism of action. One rare, known trigger of AEP is daptomycin.

CASE PRESENTATION

The patient was a 75-year-old male with a past medical history of Stage IIIb chronic kidney disease and a former tobacco smoker. He presented with 1 week of recurrent fevers, dry cough, and worsening shortness of breath. Approximately 2 weeks prior, he had been hospitalized for right metatarsal osteomyelitis with a positive wound culture for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. After consultation with infectious disease physicians, he was discharged on a 4-week course of intravenous daptomycin and ceftriaxone.

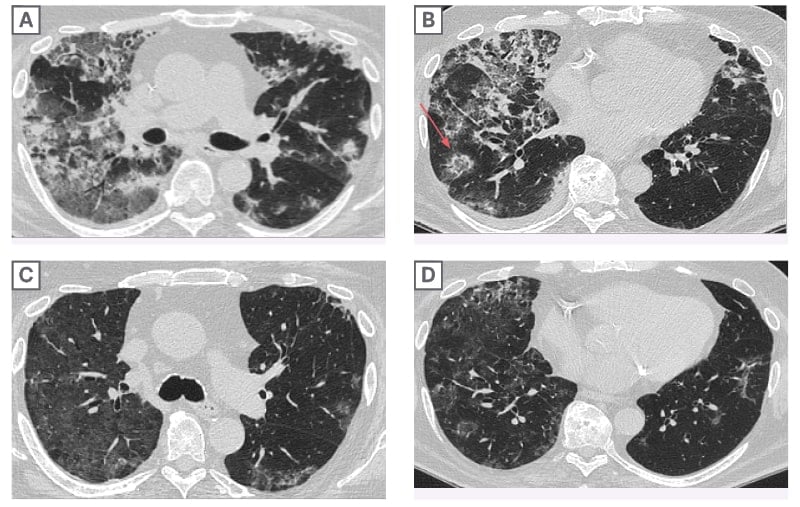

On presentation, notable vitals were a temperature of 98.4 °F, heart rate of 108 bpm, blood pressure of 164/42 mmHg, and O2 saturation of 75% on room air requiring 10 L non-rebreather. Initial notable labs were a creatinine of 2.5 mg/dL (at baseline) and a white blood cell count of 12.3×109 /L, with 2% bandemia. He did not have peripheral eosinophilia on his blood work. His initial chest radiography was concerning due to right greater than left bilateral scattered opacifications, and ground glass infiltrates. A chest CT was obtained, showing dense bilateral consolidations in the upper lobes and scattered ground glass opacities throughout both lung fields, as seen in Figure 1.

His O2 requirements prompted admission to the medical intensive care unit. His daptomycin was stopped immediately and he was started on a treatment for bacterial pneumonia. Unfortunately, his respiratory status worsened, eventually requiring a high-flow nasal cannula. Bronchoscopy was not safe to perform given his tenuous respiratory status. Empiric steroids with methylprednisolone 60 mg every 6 hours were started on Day 4 in the intensive care unit. After 3 days, his chest radiograph showed considerable improvement. Eventually, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was able to be performed, showing an eosinophil count of 11%.

The patient was discharged home with a 4-week prednisone taper and plans to repeat his chest CT in 4 weeks with pulmonary follow-up. At this follow-up appointment, his repeat chest CT showed remarkable improvement as seen in Figure 1C and 1D.

Figure 1: Chest CT at admission and at 4-week follow-up.

A) Axial lung image of the upper lobes demonstrates striking peripheral involvement in the right lung. B) Axial lung image of the lower lobe demonstrates presence of a focal area of ground glass with a rim of consolidation known as the “reversed halo sign” or “atoll sign” (red arrow), a finding characteristic of organizing pneumonia. Axial lung images of the upper C) and lower lobes D) after treatment with prednisone shows marked interval resolution of consolidations and ground glass opacities.

DISCUSSION

AEP remains an uncommon, potentially life-threatening condition that requires prompt recognition. Daptomycin is a rare trigger of AEP.

Daptomycin-induced AEP follows a particular criterion: known daptomycin exposure, fever, hypoxic respiratory failure, new opacities on chest radiography, bronchoalveolar lavage >25% eosinophils, and clinical improvement following the removal of daptomycin.1-4 Risk factors for development of the condition include male sex, chronic kidney disease, and receipt of at least 4 g of daptomycin in 4 weeks.5

The patient fit all of the risk factors for daptomycin-induced AEP. By the time of his admission, he had received approximately 10 g of daptomycin for methicillin-resistant S. aureus osteomyelitis. Additionally, he also fit the average age and sex consistent with previous literature reviews.

It is suspected that daptomycin binds to pulmonary surfactant, resulting in the release of IL-5 cytokines. This prompts the migration of eosinophils.6 While peripheral eosinophilia is seen in 77% of daptomycin-induced AEP cases,4 this patient was among the 23% that did not present with this particular lab finding. A lack of peripheral eosinophilia does not exclude the diagnosis of AEP.