BACKGROUND AND AIM

Novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was characterised by a great influence on healthcare systems all over the world. During the first peak in the spring of 2020, the number of patients was devastating and clinical decisions were restricted by system capacity. Hospitals’ emergency departments were overloaded with patients with COVID-19, and ambulances spent many hours in line for patients’ hospitalisation. To improve healthcare system performance, some elements of triage should be implemented, as in mass casualty or disaster response. Chest CT is a highly sensitive imaging modality to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia.1-3 At the start of the pandemic, with a lack of fast PCR results, some countries implemented CT-based triage at the hospital emergency department level.4,5

The aim of this work was to discuss the organisational principles of outpatient CT-based triage emergency centres.

Materials and METHODS

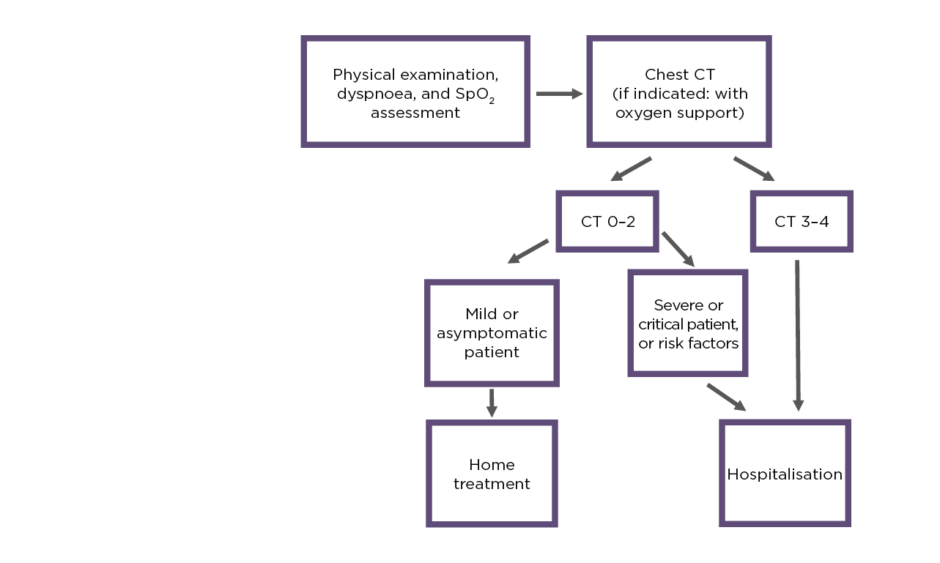

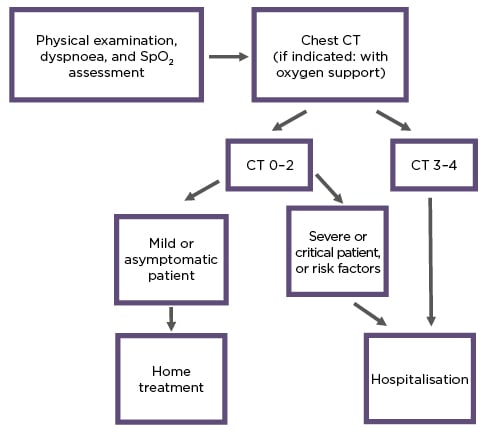

In April 2020, outpatient triage was started at the city level. Centres were equipped with CT, crash carts, vital monitors, defibrillators, and oxygen. There were consultant physicians, radiographers, and medical receptionists inside. Radiologists assessed images remotely using radiology information systems. Patients were admitted by ambulance to outpatient CT centres and assessed by consultant physicians (for symptoms, dyspnoea, and oxygen saturation levels). Based on chest CT results (severity of lung involvement) and clinical performance, decisions for hospitalisation were made. The triage algorithm is presented in Figure 1. Because of the hazardous environment, all staff were equipped with Level 2 personal protective equipment and strong infection control procedures were implemented.

Figure 1: Triage algorithm.

SpO2: oxygen saturation.

RESULTS

Between April–November 2020, 37,537 suspected and laboratory-tested patients with COVID-19 were triaged. Local radiology pneumonia severity classification (CT 1–4) was used for assessment: CT 1 with <25% of lungs involved; CT 2 with 25–50%; CT 3 with 50–75%; and CT 4 with ≥75% and more. Patients with CT 1–2 and good clinical performance were sent home for observation by ambulatory physicians. Patients with CT 3–4 and dyspnoea, oxygen saturation <94%, and comorbidities were admitted to hospital. During the 7 months, 21,986 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were diagnosed. Overall, 5,532 moderate-to-severe and critical patients were hospitalised and 32,005 patients were referred for home treatment.

CONCLUSION

Based on the study results, the authors make several proposals.

Firstly, outpatient triage of patients with COVID-19 using CT is an acceptable strategy in a respiratory pandemic environment. Secondly, CT triage is a fast tool for clinical decision-making. Thirdly, infection control is a key point for medical staff safety. ■