Meeting Summary

Approximately 80% of females with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced disease, and around 70% of these females relapse within 3 years of first-line treatment. Five-year survival for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer is less than 50%. Platinum-based chemotherapy is the cornerstone of systemic treatment; however, it is not appropriate for patients with relapsed ovarian cancer who had disease progression during previous platinum treatment, early symptomatic progression post-platinum treatment, or who are platinum intolerant. New drugs are needed to address the unmet need in patients with relapsed ovarian cancer who are not eligible for platinum-based chemotherapy. This article presents highlights from a satellite symposium conducted as part of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress 2024, which took place from 13th–17th September 2024 in Barcelona, Spain. The objectives of the symposium were to improve understanding of the current treatment pathways and unmet needs for patients with ovarian cancer who are ineligible for platinum-based therapies, to raise awareness of the rationale for targeting folate receptor α (FRα) in a variety of novel therapeutics for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC), and to review the efficacy outcomes and side effects from recent clinical trials involving antibody–drug conjugates (ADC) in PROC. In this symposium, Ana Oaknin, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain, described the current landscape in advanced ovarian cancer and the unmet need in relapsed disease; Philipp Harter, Evangelische Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Germany, explored FRα-targeted therapeutics in PROC; and Kathleen Moore, Stephenson Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma, Norman, USA, discussed ADC development beyond FRα in PROC. The symposium concluded with a lively discussion, including questions from the audience, key examples of which are included in this article.

The Unmet Need in Relapsed Ovarian Cancer: What Do We Need To Do Now?

Ana Oaknin

Approximately 80% of females with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with advanced disease (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] Stage III or IV),1 and around 70% of these females relapse within 3 years of first-line treatment.2,3 Five-year survival for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer is less than 50%.1,4 According to Oaknin: “Relapsed advanced ovarian cancer is typically incurable.” There is a significant need for better first-line treatment to improve outcomes for females with ovarian cancer.2,4,5-7

First-line treatment options in newly diagnosed ovarian cancer have expanded in recent years, especially with the introduction of poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance treatment. There was a paradigm shift in 2018, with the publication of the SOLOL1 clinical trial with olaparib.8 This was followed by PAOLA-1 with olaparib plus bevacizumab,9 PRIMA with niraparib,10 and ATHENA with rucaparib.11 All four trials showed a substantial progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with PARP inhibitor as maintenance therapy;8-12 however, whether this benefit translated to overall survival (OS) benefit was not clear.13,14 A clinically meaningful, but not statistically significant, OS benefit compared with placebo was seen with olaparib at 7 years in SOLO1,13 and with olaparib plus bevacizumab in the patients with homologous recombination deficiency, but not in the intention-to-treat population as a whole, in PAOLA-1.14 The OS results from PRIMA10 were anticipated during ESMO Congress 2024.

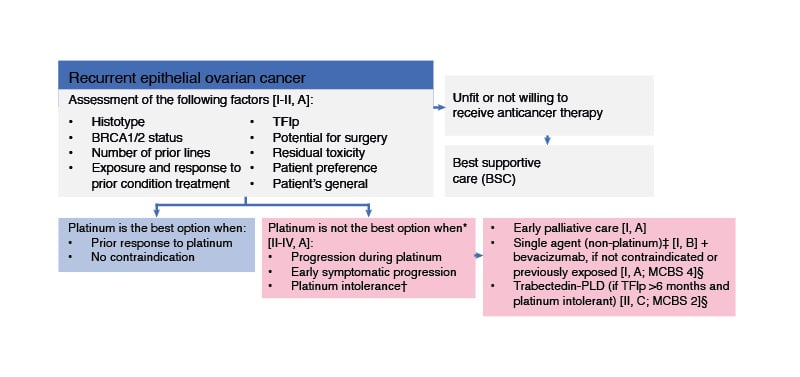

Systemic therapy for recurrent ovarian cancer is based on platinum-containing or non-platinum-containing regimens.2 There are currently no molecular biomarkers to predict the efficacy of platinum re-challenge in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.2 According to ESMO Guidelines, platinum-based therapy is not appropriate for patients with relapsed ovarian cancer who had disease progression during previous platinum treatment, early symptomatic progression post-platinum treatment, or who are platinum intolerant (Figure 1).2 These patients are recommended to receive early palliative care, trabectedin-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD; i.e., in patients with platinum intolerance who have relapsed >6 months from previous platinum, the combination of trabectedin and PLD may be recommended), or single-agent (non-platinum) treatment with conditional addition of bevacizumab (i.e., in patients without contraindications to bevacizumab and in those not previously exposed to bevacizumab),2 based on the results of the AURELIA trial.15 However, the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy did not improve OS (HR=0.85; 95% CI: 0.66 – 1.08; p <0.174).15

Figure 1: ESMO guidelines for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who are ineligible for platinum-based therapy.

Figure adapted from González-Martin A et al.2

EOC: epithelial ovarian cancer; ESMO: European Society for Medical Oncology; MCBS: ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale; PLD: pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; TFIp: treatment-free interval from last platinum.

* Patient choice and quality-of-life issues may also suggest that platinum is not the best option.

† In patients with platinum intolerance who have relapsed >6 months from previous platinum, the combination of trabectedin and PLD may be recommended [II, C; ESMO-MCBS v1.1 score: 2 for patients with platinum-sensitive disease; EMA approved, not FDA approved].

‡ Weekly paclitaxel, PLD, topotecan, or gemcitabine.

§ ESMO-MCBS v1.1104 was used to calculate scores for new therapies/indications approved by the EMA or FDA.

In AURELIA, patients with platinum resistance received investigator’s choice chemotherapy (ICC; weekly paclitaxel, PLD, or topotecan) with or without bevacizumab.15 Addition of bevacizumab to ICC was associated with a clinically meaningful and statistically significant improvement in PFS (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.38–0.60; p<0.001).15

In an exploratory analysis according to chemotherapy cohort in AURELIA, weekly paclitaxel emerged as a single-agent chemotherapy choice of interest, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 28.8% versus 7.9% for PLD and 3.3% for topotecan.16,17

Phase III studies with novel therapies added to weekly paclitaxel compared to weekly paclitaxel alone have not shown a benefit in patients with platinum resistance.18-20 This includes the AGO OVAR 2.29 trial, in which the addition of atezolizumab, a humanised programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody, to single-agent, non-platinum-based chemotherapy (weekly paclitaxel or PLD) plus bevacizumab did not significantly improve PFS or OS.21

ADCs comprise an antibody with high affinity for tumour-associated antigens (the target for ADCs); a drug payload, which is a potent chemotherapy that induces tumour cell death when it is internalised and released; and a linker that controls the release of the payload at the target site.22 According to Oaknin, ideally, the tumour-associated antigens should have a high level of expression on malignant cells, and no or negligible expression on non-malignant tissue. Moreover, the target tumour-associated antigens should be present on the cell surface, thus accessible to the ADC, and should be internalised, by which process the ADC is transported into the cell.

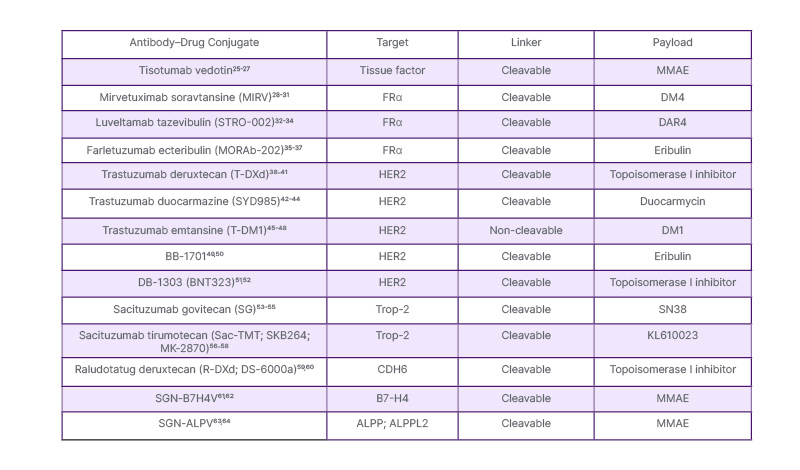

There are several ADCs in clinical development in ovarian cancer (Table 1). Mirvetuximab soravtansine (MIRV),23 targeting FRα, and trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd),24 targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), are the only ADCs that have been approved by the U.S. FDA. There are no ADCs approved in Europe.

Table 1: Antibody–drug conjugates of clinical interest in ovarian cancer.

Table compiled by Oaknin.

MMAE: monomethyl auristatin E.

Oaknin concluded: “We need to develop new drugs to address the unmet need in relapsed ovarian cancer. Antibody–drug conjugates represent another paradigm shift in the treatment of this cancer. ADCs enable us to deliver highly potent chemotherapy into tumour cells through targeting tumour-associated antigens.”

Exploring Folate Receptor-α-Targeted Therapeutics in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer

Philipp Harter

FRα is an attractive candidate for molecularly targeted approaches for ovarian cancer as it has almost ubiquitous expression on the surface of ovarian cancer cells, and can internalise large molecules containing a cytotoxic payload.65

Expression of FRα is characterised using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and classified into low, medium, and high based on the percentage of cells with staining and the intensity of staining. A study of FRα expression in pooled samples from patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer showed that around two-thirds of samples had positive staining intensity ≥2 (PS2+) in ≥50% of cells, and around one-third had PS2+ in ≥75% of cells.66

MIRV is a first-in-class ADC comprising an FRα-binding antibody, a cleavable linker, and a maytansinoid DM4 payload (a potent tubulin-targeting agent).28,29 In the confirmatory Phase III MIRASOL trial, patients with PROC, high-grade serous histology, and FRα detected by IHC with PS2+ in ≥75% of viable tumour cells were randomised to MIRV or ICC (paclitaxel, PLD, or topotecan).31 Patients included in the trial were heavily pretreated, with approximately half the patients having received three prior lines of systemic therapy.31

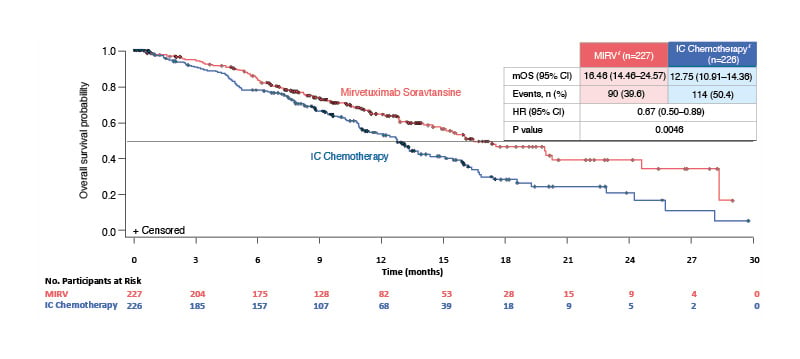

PFS, the primary endpoint, was statistically significantly longer with MIRV versus ICC: median PFS was 5.62 months (95% CI: 4.34–5.95) with MIRV and 3.98 months (95% CI: 2.86–4.47) with ICC (p<0.001).31 In terms of key secondary endpoints, ORR was 42.3% with MIRV and 15.9% with ICC (ORR difference: 26.4%; 95% CI: 18.4–34.4), and OS results were statistically significant, with an HR of 0.67 (95% CI: 0.50–0.89; p=0.0046) (Figure 2).31

Figure 2: Overall survival in the confirmatory Phase III MIRASOL trial in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer.31

Figure adapted from Moore et al.31 Data cut-off: 6 March 2023. Median follow-up time: 13.11 months.

*Intent-to-treat population.

HR: hazard ratio; IC: investigator’s choice; MIRV: mirvetuximab soravtansine; mOS: median overall survival.

Harter emphasised that this was the first Phase III trial to show positive OS in PROC comparing a new drug versus ICC. Furthermore, no new safety signals were identified compared with ICC,31 and the discontinuation rate due to adverse events in the MIRV arm was 9% versus 16% with ICC.31

Ocular events, such as blurred vision, keratopathy, and dry eye, were more common with MIRV than with ICC.31 Harter stated that the ocular side effects are manageable, but clinicians will need to learn about and gain experience with these effects.

Several other drugs targeting FRα are in clinical development.67 For example, luveltamab tazevibulin was shown to be efficacious in a Phase I trial including patients with PROC (any level of FRα expression), with an overall response rate of 31.7% and a disease control rate of 78%.33 The most common treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade in the trial were neutropenia, nausea, fatigue, and arthralgia.33 Neuropathy was also noted as an important side effect in the trial.33 A Phase II/III trial with luveltamab tazevibulin is ongoing.68

Farletuzumab ecteribulin was evaluated in a Phase I trial including patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer or other histologies.36 ORR was 25.0% and 52.4% for 0.9 mg/kg and 1.2 mg/kg farletuzumab ecteribulin, respectively.36 However, a limiting toxicity, interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis, was observed in this trial, occurring in 37.5% and 66.7% of patients receiving 0.9 mg/kg and 1.2 mg/kg, respectively.36

Another drug targeting FRα, rinatabart sesutecan, is currently being evaluated in a Phase I/II dose escalation and expansion trial,69 with initial data due at the ESMO Congress 2024.

There are already attempts to combine ADCs with other agents. For example, in the FORWARD II trial, a combination of MIRV and bevacizumab in patients with relapsed FRα-expressing ovarian cancer showed “very impressive response rates”, and was well tolerated, with adverse events as expected based on the side effect profiles of each drug, and there were no new safety signals.70

Harter concluded that MIRV has shown PFS benefit in PROC in the MIRASOL trial, and there are multiple further trials with drugs targeting FRα ongoing or under development. Areas of interest for future research include efficacy in a broader patient population regarding FRα status and effectiveness of ADCs in earlier lines of therapy.

Exploring Antibody–Drug Conjugate Development Beyond Folate Receptor-α in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer

Kathleen Moore

Moore summarised that there are numerous ADCs currently in development (including approximately 190 for solid tumours), with a variety of tumour-associated antigens and proprietary linkers, and a range of cytotoxics (mainly in two categories: microtubule inhibitors and camptothecins). ADCs differ chemically in terms of the drug-to-antibody ratio, the linkers, and the payloads; however, whether this makes a difference clinically is unknown.

According to Moore, the tumour-associated antigens aside from FRα that are of particular interest in gynaecological cancers include B7H4, claudin 6, cadherin-6 (CDH6), HER2, trophoblast antigen 2 (Trop-2), and mesothelin (MSLN).

B7H4 is a transmembrane protein widely expressed across many solid tumours.71 B7H4 expression has been reported in approximately 75% of patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, and approximately 50% of patients had >50% of cells with any B7H4 staining intensity.71 However, in Moore’s opinion, the association of B7H4 with ovarian cancer prognosis has not been validated, there are no biomarkers for B7H4, and little is known about targeting B7H4.

A total of 75 patients with ovarian cancer were treated with SGN-B7H4V in a Phase I trial, and the overall response rate across all dose levels was 20%.62 Moore considered this a “modest signal” in these heavily pre-treated patients that merited further investigation. Other ADCs targeting B7H4 in clinical research include puxitaug samrotecan (AZD8205)71 and XMT-1660.72

Claudin 6, another transmembrane protein, is highly overexpressed in many solid tumours, including ovarian cancer, and has little to no expression in non-malignant tissues.73 Hence, Moore noted that claudin 6 may be the closest to a lineage marker (i.e., a ‘tumour-specific’ rather than a ‘tumour-associated’ antigen) among the solid tumour targets.

Initial results from a first-in-human study of TORL-1-23, an ADC targeting claudin 6, in epithelial ovarian cancer showed an ORR of 32%.73 Moore considered claudin 6 to be a “different and exciting target for gynaecological cancers”.

CDH6 is a transmembrane protein that is highly overexpressed in epithelial ovarian cancer.74 Moore noted that the function of CDH6 in ovarian cancer and the impact on prognosis has not yet been fully elucidated. Raludotatug deruxtecan (R-DXd), an ADC targeting CDH6, has been tested in a Phase I trial in patients with PROC, irrespective of biomarkers.75 The confirmed overall response rate was 48.6% (95% CI: 31.9–65.6) in the 4.8–6.4 mg/kg ovarian cancer cohort, duration of response was 11.2 months (95% CI: 3.1–not estimable [NE]), and median PFS was 8.1 months (95% CI: 5.3–NE).75

Moore described these results as “a very strong signal right out of the gates”; however, this is not sufficient to progress into Phase III trials versus standard-of-care treatments because dose optimisation and therapeutic windows for ADCs need to be understood. Therefore, the REJOICE-Ovarian01 randomised Phase II/III trial is being conducted to identify the optimal dose of R-DXd (4.8, 5.6, or 6.4 mg/kg) for efficacy and safety to inform the Phase III trial.76

CUSP06/AMT-707 is another ADC targeting CDH6 of interest for the treatment of ovarian cancer, and clinical data are awaited.77,78

HER2 has long been known to be a target in ovarian cancer; however, this target has received little ovarian cancer research attention until recently.79 HER2+ IHC 3+ is uncommon in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (2–5%),80-82 whereas HER2+ IHC 2+ occurs more frequently (8–18%).80,82,83 The incidence of HER2+ IHC 1+ is not yet known.

ORR in patients with PROC receiving T-DXd, which targets HER2, in the DESTINY-PanTumor02 trial was 45% (18/40) for all patients, 63.6% (7/11) for IHC 3+, and 36.8% (7/19) for IHC 2+;80 however, these results need to be confirmed in a larger dataset.

The frequency of strongly positive cases of Trop-2 with immuno-staining is >40% of serous, approximately 40% of endometrioid, approximately 30% of mucinous, and approximately 20% of clear cell ovarian cancers, as well as >20% of carcinosarcomas of the ovary.84 There is growing interest in ADCs targeting Trop-2 in ovarian cancer.

Finally, MSLN is highly overexpressed in many solid tumours, and has recently re-emerged as a target of interest in ovarian cancer following a confirmed ORR of 41.9% (95% CI: 24.5–60.9) with RC88, an ADC with a monomethyl auristatin E payload, in a platinum-resistant population.85

Moore concluded that ADCs are some of the most promising new agents in gynaecological cancers, and the variety of ADCs in development for ovarian cancer is exciting; however, better understanding of sequencing of ADCs, payload factors, and potential resistance mechanisms is needed.

Digesting the Data: Reflections on Antibody–Drug Conjugates

Panel discussion with all speakers

Four Key Questions from the Audience During the Panel Discussion are Covered Below

The experts discussed the potential use of technology, such as analysis of circulating tumour cells or circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA), to alleviate the delay in obtaining tissue biopsies in clinical trials. Moore considered that ctDNA technology in ovarian cancer is not sufficiently mature or reliable to warrant replacing tumour biopsies and biomarkers with a circulating marker. As technologies improve, this approach may be helpful as part of optimising treatment for patients.

The approach for the patient newly diagnosed with PROC was considered, including whether clinicians should start testing for FRα early in the patient journey. Harter noted that FRα testing does not necessarily have to be conducted early, unless it is important for the patient’s therapy; however, clinicians should be aware of the location of the patient’s tissue specimens, with these specimens ideally kept in the centre where the patient is being treated, to allow timely testing, if and when required.

A further topic in the panel discussion was the management of ocular toxicity under MIRV therapy. Oaknin emphasised that clinicians should be aware of the type of eye events the patient might develop with this treatment, ensure that they follow their patients carefully from the beginning of therapy, and identify ocular events as early as possible. In addition, clinicians should regularly ask patients if they are suffering from any kind of ocular symptoms and refer patients to an ophthalmologist as necessary. Moore emphasised that patients should be encouraged to inform their doctor even if they are having only mild ocular symptoms so that mitigation strategies can be implemented. In addition, Moore stated that it is important that clinicians acknowledge the patient’s ocular symptoms and treat them early.

Whether treatments have an impact on the biology of the cancer cell, and the possibility of restoring platinum sensitivity with MIRV, was also considered by the panel. Moore outlined that research is required in this area, including assessing the efficacy of paclitaxel before and after MIRV, responses with subsequent lines of therapy, and treatment sequencing. Moore added that MIRV and weekly paclitaxel are two of the most active agents in the platinum-resistant space, so these are the treatments of choice (in the USA) if the patient has not yet received these drugs and has no contraindications.