Interview Summary

Endometrial cancer is one of the most common gynaecological cancers in high-income countries, and the incidence is rising significantly. There has recently been a crucial increase in understanding of tumour biology in endometrial cancer, as well as a significant improvement in tailoring surgery and radiotherapy, and the introduction of targeted therapies. In the context of these developments, novel initiatives are needed to increase awareness of new treatment modalities, and infrastructure is required to enable optimal management of patients with endometrial cancer. A co-ordinated, collaborative, multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach in endometrial cancer management promotes shared decision-making and enables comprehensive care of patients, from diagnosis through treatment, via a range of medical specialities and support initiatives. For this article, EMJ conducted an in-depth interview in August 2023 with two key opinion leaders, Domenica (Ketta) Lorusso from the Catholic University of Rome, Italy, and Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Gemelli IRCC, Italy; and Jalid Sehouli from Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, both of whom have a wealth of experience and expertise in the clinical management of endometrial cancer, and have conducted numerous scientific projects in this field. The experts gave valuable insights into topics such as diagnosis and disease staging in patients with endometrial cancer, measuring the value of an endometrial cancer MDT, and quality control and monitoring of MDT meetings. Lorusso and Sehouli also explored ideas on how to optimise multidisciplinary care in patients with endometrial cancer, including covering aspects of patient management beyond treatment, and how to maintain effective communication between the MDT and the patient. Further topics discussed included empowering nurses in the MDT, managing clinical trial opportunities for patients with endometrial cancer, and aligning MDT recommendations with the expectations of the patient. Finally, Lorusso and Sehouli described what the future of the multidisciplinary management of patients with endometrial cancer might look like.INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynaecological cancer in high-income countries.1 It often presents at an early stage, when the disease is still confined to the uterus,2 and is frequently associated with comorbidities.3 An MDT approach is considered the gold standard for diagnosing and treating cancer, and is a developing area of oncology.4-6 This approach has been recommended for various aspects of endometrial cancer care, including management of metastatic disease and relapse,7 to increase discussion about obesity and referral to a weight loss clinic in patients with low-risk endometrial cancer who are obese,8 and to address preserving fertility in premenopausal patients with Stage I disease.9 Central MDT review has also been advocated for providing individualised treatment recommendations for patients with rare presentations of endometrial cancer.10 There have been reports of more limited availability of gynaecological oncology multidisciplinary or specialist care in lower-volume compared with in higher-volume hospitals.11 A co-ordinated, multidisciplinary approach from healthcare professionals, incorporating evidence-based guidelines12 and quality indicators,13 is necessary for managing patients with endometrial cancer, to diagnose and treat the disease, provide support for the various needs of the patients, and optimise outcomes.14

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE IN ENDOMETRIAL CANCER IS NOT YET A GLOBAL APPROACH

Lorusso reflected that although an MDT approach to support patients with endometrial cancer is becoming increasingly common in clinical practice across the oncological community, it is not yet a global approach. The medical and surgical treatment of endometrial cancer is increasing in complexity, necessitating the involvement of healthcare professionals from different specialisms for diagnosing and treating patients. Therefore, a multidisciplinary care approach should be adopted globally to provide optimum care for patients with endometrial cancer. According to Sehouli: “An MDT approach is not yet the gold standard for endometrial cancer care (it is far away from any metal), because discussion is lacking on the optimal procedure before surgery based on the molecular and immunohistochemical signature. Furthermore, most treatment decisions do not take into account comorbidities and sociodemographic aspects of the individual patient.”

DIAGNOSIS AND DISEASE STAGING IN PATIENTS WITH ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

Lorusso explained that abnormal uterine bleeding is an early sign of endometrial cancer,15,16 and should trigger immediate investigation. Sehouli noted that serous carcinoma17,18 and carcinosarcoma19 tumour types can induce other abdominal symptoms, including pelvic pain, bloating, and discomfort, when the tumour spreads to the peritoneum or bowel, and these symptoms should also prompt clinical inquiry. Endometrial cancer mostly occurs in post-menopausal females,16 but can develop during peri-menopause,20,21 and, rarely, in pre-menopausal females.22 Abnormal uterine bleeding as a sign of endometrial cancer in peri-menopausal females is confounded by the bleeding changes related to hormonal fluctuations in the menopausal transition,23 and this may delay diagnosis. Lorusso emphasised that it is essential for primary care professionals to refer patients with abnormal bleeding for diagnosis and preparatory work-up at the first sign of potential disease. The patient should be referred for vaginal ultrasound evaluation, then hysteroscopy with biopsy to obtain diagnosis. Lorusso noted that only in those healthcare systems in which these procedures are performed systematically and in a timely manner can an immediate histological diagnosis be obtained. The preparatory work-up, including CT scan for radiological staging, should be conducted as soon as possible after diagnosis is confirmed.

Lorusso pointed out that disease characterisation in patients with endometrial cancer is not only a clinical procedure. After surgery, information is needed on which of the four molecular subtypes of endometrial cancer the patient has (polymerase epsilon exonuclease domain mutated, mismatch repair deficient, p53 wild-type/copy-number-low, or p53-mutated/copy-number-high),24 as mandated in the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging guidelines.25 The involvement of a pathologist and a molecular pathologist in the MDT enables histological and molecular profiling data to be provided in parallel. These data are important for FIGO staging,25 and class risk stratification, which guides decisions about adjuvant treatment for patients with endometrial cancer.

According to Lorusso, endometrial cancer is currently the only gynaecological malignancy that is increasing in incidence and mortality, with elevated mortality rates also related to the decentralisation of treatment.12,26-29 For several years, endometrial cancer was considered “a level B disease” that was relatively easy to manage, because abnormal uterine bleeding was an immediate and clear sign, and most patients presented with Stage I disease. This meant that clinical research conducted on this type of cancer was limited. The complexity of endometrial cancer has recently become evident, with the discovery of four different types of tumour, and this has changed the situation completely. A systematic approach that includes referring patients to a specialist referral centre is now required.

MEASURING THE VALUE OF AN ENDOMETRIAL CANCER MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

How the value of an endometrial cancer MDT is measured, and which key performance indicators should be used, is “a very difficult question,” according to Lorusso, because there are no guidelines on how to measure the value and performance of an MDT, and individual institutions must set their own parameters and monitoring processes. In Lorusso’s institution, there are no well-defined key performance indicators, but every 3 months, there is a review of time performance statistics and the number of patients discussed at MDT meetings, including time from diagnosis to surgery, from surgery to histological reporting, from surgery to molecular characterisation, and from diagnosis to starting treatment. Patient compliance with treatment is also evaluated. These parameters are reviewed periodically to identify where in the process there is room for improvement.

Sehouli explained that there are no guidelines to specify which healthcare professionals should be included in an MDT. In Germany, where Sehouli is based, at least one gynaecological oncologist must be present at MDT meetings, and the presence of a pathologist, radiologist, and medical oncologist is generally required. The lack of guidelines means that the selection of MDT members may differ between countries. Sehouli added that quality indicators for MDT meetings are also currently not standardised globally, and might include patient compliance, patient adherence, and whether referral or participation in a clinical trial was considered. There is no system in place worldwide to define and ensure quality control and monitor performance of MDT meetings. Commonly, institutions only look at which healthcare professionals have been involved in the MDT, and how many patients have been presented at the meetings. Lorusso highlighted that one criterion that can be easily monitored is the number of patients discussed in the MDT meeting.13,30 At Sehouli’s institution, approximately 90% of patients with endometrial cancer are discussed at MDT meetings, whereas as few as 5% of patients may be presented to MDTs at other centres, as the gynaecologist takes sole responsibility for patient management.

Lorusso and Sehouli emphasised that the number of patients discussed in an MDT meeting and entered into clinical trials as key performance indicators is not the whole story. The time taken to discuss each patient depends on the complexity of their case, and there is often insufficient time for a comprehensive discussion of the more complex cases. Discussion at a second MDT meeting is not offered in all centres. The number of patients put forward for clinical trials also differs between institutions as only those centres that take part in clinical trials are likely to offer participation. Sehouli summarised that the impact of the MDT treatment decision-making process needs to be measured in terms of the efficacy of treatment; using objective markers, such as tumour remission; progression-free survival and overall survival; patient-reported outcomes; toxicity of treatment, particularly for targeted therapy; patient adherence; and the number of patients who entered clinical trials.

QUALITY CONTROL AND MONITORING OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM MEETINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Lorusso and Sehouli outlined that quality control and monitoring of MDT meetings and recommendations are required to maintain quality of patient care, improve efficiency, address and minimise the occurrence of incorrect decisions made during MDT meetings, assess the efficacy and toxicity of the treatment recommended by the MDT, and monitor patient adherence to treatment. Infrastructure needs to be in place to support these quality control and monitoring activities to ensure the treatment decision-making process is moderated.

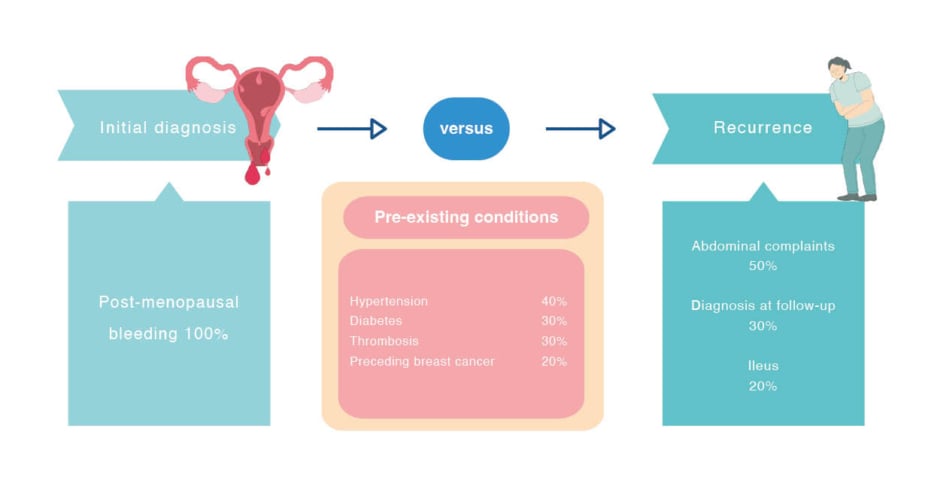

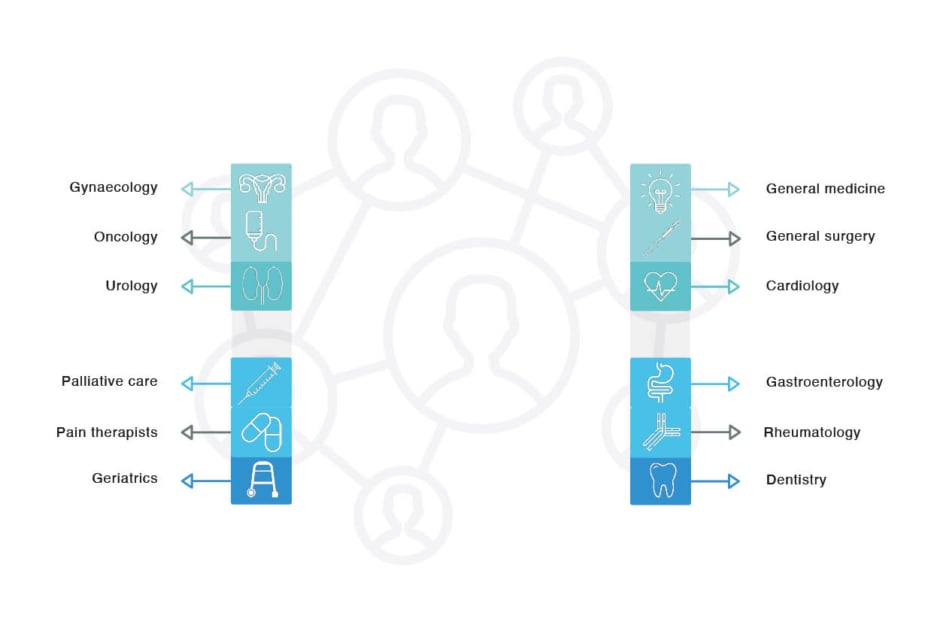

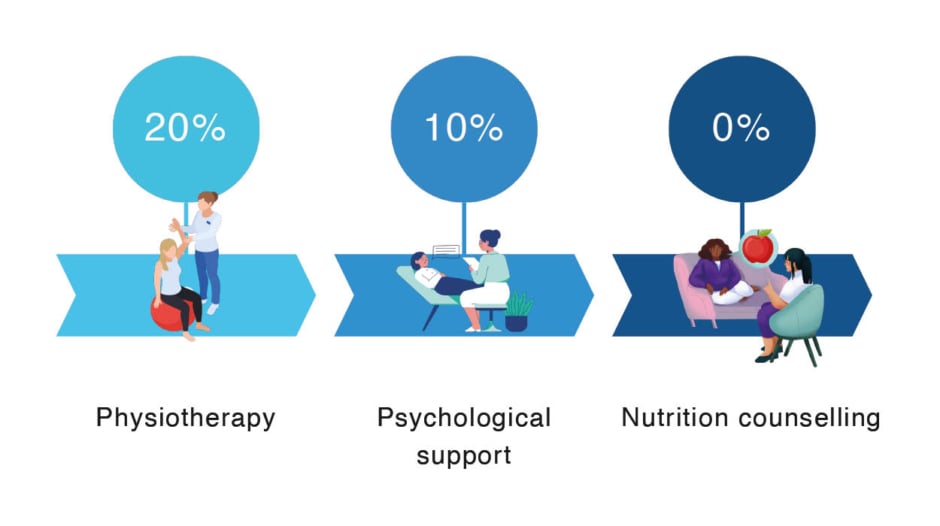

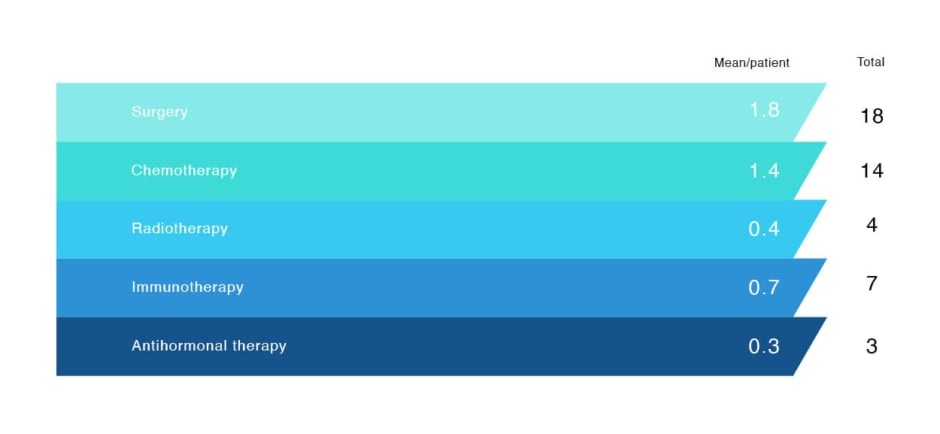

Sehouli highlighted that implementing quality control and monitoring procedures into multidisciplinary care, as part of the drive to optimise management, needs to be considered in the context of the demand placed on MDTs. A survey of 10 patients with recurrent endometrial cancer at Sehouli’s centre showed the complexity of management of these patients and the necessity for a well-co-ordinated multidisciplinary approach to optimise care (Figures 1–4). These patients required a range of medical specialities, treatments, and outpatient complementary support to manage their disease and various comorbidities. This visualisation of the management requirements associated with a small cohort of representative patients with recurrent endometrial cancer clearly signifies the huge challenge faced by MDTs, and confirms the importance of a quality control procedure to maintain standards in this complex setting.

Figure 1: Symptoms.

Figure 2: Involved medical specialities.

Figure 3: Outpatient complementary support.

Figure 4: Therapy.

OPTIMISING MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE IN PATIENTS WITH ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

Sehouli specified that the process of forming an MDT is not the endpoint to optimise the multidisciplinary management of patients with endometrial cancer. To optimise management requires healthcare professionals to be trained and incentivised to work together effectively in a multidisciplinary context. Furthermore, patient empowerment is lacking, but this is improving slowly as patients learn about endometrial cancer, MDTs, and clinical trial involvement. Lorusso concurred that it is not enough to just establish an MDT for diagnosing and treating patients with endometrial cancer because, for many patients, this is a metabolic disease, and is often associated with various comorbidities, which require lifestyle changes and specific treatments to improve patient health and quality of life.

According to Sehouli, multidisciplinary management of patients with endometrial cancer requires a novel approach to optimise care before, during, and after treatment. New networks of excellence are being created for patients with endometrial cancer. In 5–10 years, there will be specialist units for endometrial cancer, as there are for breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Lorusso emphasised: “Multidisciplinary care for endometrial cancer is far from perfect, but there is a constant strive to create something better for our patients.”

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE SHOULD COVER ASPECTS OF PATIENT MANAGEMENT BEYOND TREATMENT

MDT meetings are a forum for treatment decision-making, and conduct of these meetings is required as part of the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) centre certification process.13,30 However, multidisciplinary care should also cover aspects of patient management that go beyond treatment, such as developing an holistic approach that encompasses all aspects of female health (including sexual and sociodemographic factors), empowering patients (e.g., to seek a second opinion), and defining the healthcare professionals who are responsible for the patient at each stage of their treatment journey. According to Sehouli, aspects of patient management that are currently missing from the multidisciplinary approach include psycho-oncology, optimising treatment of comorbidities, and lifestyle-based care for patients for whom cancer treatment is not recommended. Sehouli considered the MDT approach to be a learning tool that requires support and investment to improve the process, build trust with patients, and create team-building opportunities for healthcare professionals from different disciplines.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM FOR THE PATIENT AND THE TEAM MEMBERS

Lorusso expressed that multidisciplinary care is beneficial for the patient in regard to early and correct diagnosis, optimum treatment, and clinical trial access. In general, the more healthcare professionals who discuss the patient, the better the treatment decisions. Sehouli agreed that the MDT is important for the patient, and that reaching a decision through an MDT is a quality indicator for better treatment. The experts remarked that the MDT setting is also advantageous for the healthcare professionals involved in terms of exchanging information and ideas, gaining knowledge, and improving understanding of other disciplines within the team.

EFECTIVE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM AND THE PATIENT

Lorusso and Sehouli emphasised that a key aspect of a well-run MDT is effective communication between the MDT and the patient, and that healthcare professionals should consider how to better communicate treatment decisions to their patients. Sehouli commented that patients often do not know what is meant by an MDT. Also, patients have likened the MDT meeting to a court hearing, and expressed concern that decisions are made without considering their perspective. The experts recommended that healthcare professionals should explain to their patients what an MDT is, describe the MDT meeting process, and highlight the benefits of multidisciplinary care, including the advantages of making treatment decisions as a team. Lorusso underlined that the extent of communication with the patient is primarily defined by the attitude of the physician, and ranges from full disclosure about the MDT process, to disinclination to discuss the involvement of the MDT, as it may reflect on their professional capability.

EMPOWERING AND ENABLING NURSES IN THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM

Lorusso explained that the role of physicians is becoming much more complex and demanding, particularly regarding the management of difficult treatment side effects, and there are declining numbers of physicians globally. According to Lorusso, the only way to address the impact of these issues on patient care is to involve more healthcare professionals, including nurses and care managers, in the MDT to support physicians, and to maintain quality of care. Lorusso expects nurses to take on increasing responsibility for managing treatment side effects in patients with endometrial cancer, to lead patient education initiatives, and to become the interface between the patient and the hospital in the future.

Sehouli agreed that a set-up with all relevant healthcare professionals and the patients involved in the multidisciplinary care process would be ideal, but “there is no ideal in endometrial cancer care.” According to Sehouli, there are two major challenges to overcome. The first challenge is to understand the MDT process in a broader way. The process includes not just a 10–15-minute discussion in the primary MDT meeting, but all the preparation before and the data collection after the meeting, and separate discussions between different disciplines involved in the patient’s care under the umbrella of the primary MDT meeting. The second challenge is to empower patients and healthcare professionals to be heard. Sehouli suggested that involving a nurse in the MDT meeting has limited benefit currently, because nurses are not yet accepted as involved in the treatment decision-making process. Training and empowering nurses about treatment decision-making will give them confidence and responsibility, and may provide them with the opportunity to lead the decision-making process, as well as patient education and training in the future. Infrastructure needs to be in place and resources available to enable nurses and other healthcare professionals to attend MDT meetings, for example, to ensure that care of patients on the hospital ward is covered.

MANAGING CLINICAL TRIAL OPPORTUNITIES

Lorusso referred to a survey conducted by a patient advocacy group in Italy on patients’ attitudes to clinical trials,31 and the results of this indicated that “we are very far from patient empowerment.” Physicians are generally considered by patients to be the “manager of the disease,” and are usually able to convince patients to take part in clinical trials unless there are logistical issues. Over the last decade, Lorusso has observed a shift in patients’ attitudes, from being scared to enter clinical trials, to now becoming more demanding about the opportunity to participate. This change is the result of increased patient awareness of the reasons for, and potential benefits of, clinical trials. In line with this, Sehouli observed that the barrier to clinical trial participation is usually not the patients.32 Even ‘fragile’ cohorts, such as elderly females and migrants, generally express an interest in participating in clinical trials, but physicians rarely offer these cohorts the opportunity.33

Sehouli indicated that efforts are needed to improve visualisation of clinical trials beyond inclusion on websites such as ClinicalTrials.gov, to involve patients in clinical trial planning, to optimise how positive and negative results of clinical trials are communicated to patients and the research community, and to learn how to make the next clinical trial more effective. Furthermore, physicians are hesitant to recommend therapies that are outside their experience, and require information and support to fully engage with the clinical trial process.

An app is currently being used at Sehouli’s institution to inform patients with endometrial cancer and their physicians about any clinical trials in progress for which the patient is eligible. The patient enters a minimal dataset, including their molecular signature, into the app, the app scans the dataset, and then notifies the patient and their physician whether there is a suitable clinical trial running. A tool such as this to inform about clinical trials in endometrial cancer addresses a gap in information, and potentially increases treatment options for patients.

ALIGNING THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM WITH THE EXPECTATIONS OF THE PATIENT

Sehouli acknowledged that it is important to clarify upfront the goal of the MDT treatment decision-making process, whether this is cure, remission, symptom control, or some other target. These treatment endpoints should be discussed with the patient to ensure they align with their expectations on quality of life, daily activities, and other personal factors. Sehouli stated: “Ideally, the treatment decision-making process should start with understanding the patient’s perspective and expectations, and then defining the treatment goal, not with tumour imaging and pathology, but this is rarely the case.” MDTs might need to take a long-term approach, involving regular monitoring of patient outcome, compliance, and satisfaction, to ensure treatment continues to be aligned with patient expectations, and to enable treatment adjustments to improve compliance, where necessary. Sehouli also underlined the significant need for more information and educational materials for patients to empower them in the treatment decision-making process. A further gap in care is cancer survivorship for females with endometrial cancer. Symptoms such as fatigue, lymphoedema, neurotoxicity, and problems concerning sexuality are often inadequately addressed in the cancer care programme.

FUTURE PROSPECTS AND CONCLUSIONS

Lorusso proposed that endometrial cancer treatment will become increasingly personalised according to molecular profile and mutation target. This is already a reality in the advanced setting, and will move to the adjuvant setting, and also to staging and risk stratification. Immunotherapy will play a definitive and major role in microsatellite instability-high tumours, and in combination therapy for microsatellite stable tumours. The p53 mutation has a well-defined prognostic role, but may also have a predictive role for treatment decisions in the future. Antibody-drug conjugates will enter the clinic, and more personalised surgery based on molecular profile is a possibility. These developments, as part of a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach, will broaden treatment options, and likely improve outcomes for patients with endometrial cancer. Although the focus for managing patients with endometrial cancer is on diagnosis and treatment, for many patients, this cancer is a metabolic disease, and a multidisciplinary approach that encompasses lifestyle changes is of utmost importance. Including factors such as nutrition support and physical activity into the multidisciplinary setting will contribute to a necessary global change in lifestyle that will improve patient quality of life and outcomes.

Sehouli concluded that MDTs currently do not have the time and resources to provide comprehensive care for all patients with endometrial cancer; therefore, it is necessary to establish MDTs beyond the individual institutions. Digital platforms to visualise the perspectives of patients and healthcare professionals, and to inform patients and the research community about ongoing or planned clinical trials, are an important development for endometrial cancer research. The creation of networks of excellence over the next few years will provide access to different levels of MDT, thus enabling patients to be ‘triaged’, and multidisciplinary care to be delivered more efficiently. Financial incentives could be given as a source of funding to support MDT meetings and activities, and to motivate centres to develop and improve multidisciplinary care practices for patients with endometrial cancer.