BACKGROUND

Patients with metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (STS) have a poor prognosis with a median survival of 12–14 months.1 First-line therapy consists of anthracycline-based cytotoxic chemotherapy. Doxorubicin remains the most active single agent with a response rate of 25%.2,3 The treatment of patients with advanced STS who are unsuitable for front-line cytotoxic therapy because of age, comorbidities, or poor performance status poses a treatment dilemma. Pazopanib is a multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for second-line and beyond treatment for metastatic STS. Approval was based on the PALETTE study, a Phase III study of 372 patients with metastatic STS who had progressed on standard chemotherapy.

In this trial, a median progression free survival (PFS) of 4.6 months in the pazopanib arm compared to 1.6 months in the placebo arm, and overall survival (OS) of 12.5 and 10.7 months, respectively, was observed.4 Treatment was well tolerated; the most common adverse events were fatigue, diarrhoea, nausea, weight loss, and hypertension.4 EPAZ, a noninferiority study comparing doxorubicin and pazopanib in the front line in patients >60 with nonresectable or metastatic STS, noted a PFS of 5.3 months for doxorubicin compared to 4.4 months for pazopanib (p=0.993), and OS of 14.3 and 12.3 months, respectively (p=0.735).5 Herein, the authors report a Phase II study to evaluate pazopanib as a first-line agent in patients with nonresectable or metastatic disease who were not felt to be candidates for cytotoxic chemotherapy by the treating physician.

METHODS

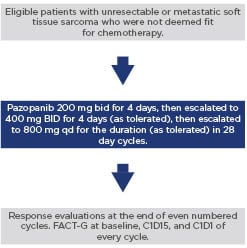

Eligible patients had histologically confirmed nonresectable or metastatic STS, were at least 18 years old, not a candidate for chemotherapy as determined by the treating physician, and had not received prior systemic therapy for sarcoma. Initial starting dose of pazopanib was 200 mg twice daily and titrated to 800 mg daily (Figure 1). The primary endpoint was clinical benefit rate (CBR) (complete response + partial response + stable disease per RECIST 1.1) at 16 weeks. The sample size of 56 evaluable patients was calculated to provide 80% power to test a hypothesised CBR of ≥35% against an unfavourable CBR of ≤20%. If ≥17 patients achieved benefit, the null CBR of 20% would be rejected at a nominal 5% alpha level (actual alpha=0.043). Secondary endpoints included PFS rate, OS, quality of life, and serum biomarkers.

A total of 56 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The median age was 78.7 years (60–91 years), ECOG 0–2 (14% of patients ECOG 2), 82% of patients had metastatic disease. Histologic subtypes included liposarcoma (n=2), leiomyosarcoma (n=21), UPS (n=19), and other (n=14). The CBR was 37.5% (21/56), 95% Wilson confidence interval (CI): 0.2492–0.5145, 2-sided exact binomial test p=0.0019. An additional 17.5% of patients (eight stable disease, two partial response) could not be confirmed by a second scan, and 18% were not evaluable for best response (n=10). The median PFS was 3.67 (2.05–24.14) months, and PFS rate at 4 months was 44% (95% CI: 0.33-0.6). Median OS was 13.22 (95% CI: 8.46–not reached) months. No new or unexpected adverse events were seen; the most common Grade I–II adverse events were diarrhoea, nausea, and fatigue. The most common Grade III-IV adverse events were hypertension and liver function test abnormalities. No change was seen in quality of life scores by drug treatment.

Figure 1: Study schema

CONCLUSION

In patients for whom cytotoxic chemotherapy is not an option, treatment for STS is limited. The primary endpoint of this study was met with a CBR of 37.5%. These data suggest there is a benefit to front-line pazopanib in this patient population.