Meeting Summary

Dravet syndrome (DS) and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) are developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEE) that onset in childhood, and persist lifelong. In both, non-seizure symptoms (NSS) include intellectual disability, psychiatric symptoms, speech and communication difficulties, motor and gait difficulties, appetite and eating difficulties, autism spectrum characteristics, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and sleep disorders. The NSS impact health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for the affected individual and the caregiver, considering personal time, sleep, finances, energy, and family and social relationship. In this industry-sponsored symposium, three leading ex-perts in DEEs discussed NSS, and how properly assessing and tracking these can lead to more informed understanding of an individual’s needs. This can help to guide treat-ment for NSS and, subsequently, increase HRQoL for both the individual and their caregivers.

Introduction

DS, which has a prevalence of 1.5−6.5/ 100,000,1-5 is predominantly due to variants in the gene SCN1A affecting the sodium channel.6 Onset is usually in the first year of life, with prolonged and recurrent seizures. Further seizure types emerge, including myoclonic, absence, and focal seizures with impaired awareness, which persist into adulthood. Prior to seizure onset, development is usually typical, or with only minor delay. However, with time, varying degrees of developmental delay and intellectual disability become apparent, as well as motor dysfunction and crouch gait.7,8

LGS represents up to 10% of childhood DEEs, with age of onset up to 18 years old, but typically between 1.5−8.0 years.7,9 One study of LGS found an estimated lifetime prevalence at age 10 years of 0.26/1,000;10 others have shown that it is more prevalent in males than females (around a 1.55:1.0 ratio).11,12 Although causes of LGS can include head trauma, perinatal complications, infections, hereditary metabolic disorders, and congenital central nervous system malformations, in up to one-third of individuals, there is no identifiable aetiology. LGS may also occur with varying genetic variants, although no consistently associated single gene has been identified. LGS is identified by the presence of tonic and other seizures, a characteristic electroencephalogram pattern, and cognitive impairment. Further seizure types, including atypical absence, atonic (drop), myoclonic, tonic clonic, and focal seizures, occur in variable frequency. Classic electroencephalogram patterns include generalised paroxysmal fast activity, which is most commonly seen in sleep, as well as generalised slow spike-and-wave. In many individuals with LGS, there is severe intellectual disability by the time of seizure onset, and declining cerebral function over time.9

Along with epilepsy-associated symptoms, there are myriad NSS in people with DEEs.13-25 The occurrence and assessment of NSS, as well as the impact of NSS on HRQoL for individuals with DS or LGS and their caregivers, were discussed in this industry-sponsored seminar by Elaine Wirrell, Chief of Child Neurology and Director of Pediatric Epilepsy at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA; Kette Valente, Director of the Neurophysiology Laboratory at the Institute and Department of Psychiatry, University of São Paulo, Brazil; and J. Helen Cross, Director of the University College London (UCL) Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, UK.

Non-Seizure Symptoms in Individuals with Dravet Syndrome and Lennox–Gastaut Syndrome

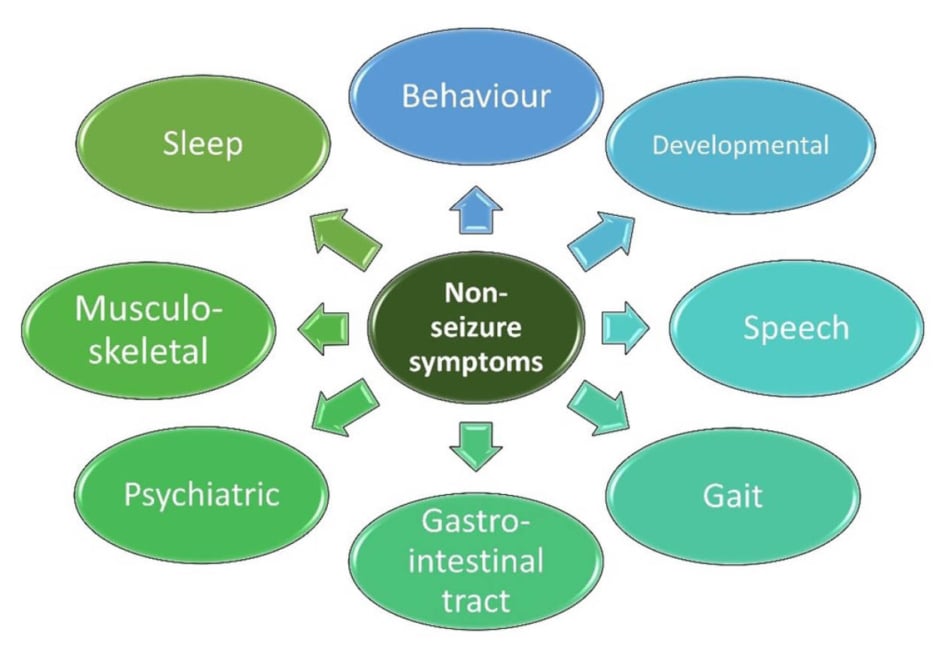

NSS in people with DEEs include those that can affect cognition, behaviour, sleep, motor function, and the gastrointestinal tract (Figure 1).8,26 The overall prevalence of depression and anxiety is also higher in children with DEEs, suggesting common pathogenic mechanics or neural basis.27 Systematic assessment of NSS throughout life shows an increasing neurodevelopmental gap between patients and controls over time, with some NSS persisting and worsening into adulthood (e.g., gait).22,28

Figure 1: Potential non-seizure symptoms in people with developmental and epileptic encephalopathy.8,26

As such, there is a need for a multidisciplinary team approach for the individual with DEEs, and for caregiver support.29 “Holistic care is about much, much more than treating the seizures,” said Wirrell. “We need to listen to the families [and] ask them [about] their priorities, and we need to address the NSS.” “One of the things that is really important,” said Cross, “is to involve a specialist nurse or psychologist who has experience in DEEs, and who really understands the range of comorbidities that go along with these conditions, and what these families go through.” Much support can also be provided by rare epilepsy disease organisations, which are needed, Cross continued, “as it can be very isolating to have a child with a specific disorder.”

Behavioural difficulties occur in at least one-third, and up to all individuals with DS, depending on the criteria.16,17,30 For at least 20%, this leads to a formal attention deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnosis.13,15,16 Around 30−70% of individuals with DS exhibit autism spectrum symptoms.15,16,30-32 Behavioural problems in children with LGS also include hyperactivity, aggression, and autistic traits,25,33,34 although the latter are seen at a lower prevalence than in people with DS.35 Behavioural difficulties may worsen in adolescence, with studies showing such behaviours can be exacerbated by communication challenges and comorbid mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression.7,33,36

Occurrence of tonic seizures during sleep is a core feature of LGS, leading to sleep disturbances,34 which may intrude on HRQoL.37 In DS, along with nocturnal seizures, sleep problems may include difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep, sleep breathing disorders, and sleep-wake transition disorders.38

Motor difficulties in people with DS can include ataxia, crouch gait, and fine motor problems,13,15-17,39 with around half of individuals with DS using a wheelchair, with numbers increasing with age.14,19 Speech is affected in around 80% of individuals with DS, with some children being non-verbal.15 Physical disabilities are typical in people with LGS.24,34 Wheelchair use may be necessary again, due to both gait problems and the need to remain seated due to the risk of seizure-related falls.24,25,37

Individuals with DS may experience gastrointestinal issues, resulting in a loss of appetite and vomiting.14,16 Similarly, individuals with LGS may face feeding difficulties, such as increased dysphagia, with age.40 In some cases, feeding tubes may be necessary for about one-fifth of individuals with DS, and one-quarter of those with LGS.25

A worrying finding in people with DS and LGS is increased mortality rates compared to both overall population mortality rates and other types of epilepsy. For instance, while mortality rates for people with epilepsy are around 0.88/1,000 person years,41 rates for LGS are around 6.12/1,000 person years,42 and in DS they are around 15.84/1,000 person years.43 Mortality is most often due to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, prolonged seizures, seizure-related accidents, or aspiration pneumonia due to severe neurological disability.20,44 Results such as these highlight the need for optimal seizure control.

Health-Related Quality-of-Life

Both seizures and NSS of DS and LGS can significantly impact the HRQoL of both the individual and their caregivers, with studies showing significantly lower scores on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) for both physical functioning and psychosocial health,45 and caregiver concerns around communication difficulties, developmental problems, mobility issues, and behavioural problems in individuals with DS.16 In interviews with parents of children with LGS, limitations in communication, as well as social and recreational activities, drive frustration and aggressive behaviour.37 Impacts on HRQoL can also be interactive with NSS; for example, sleep problems can impact daily living, recreational activities, and schooling; and cognitive impairment can impact communication, relationships, schooling, and emotional wellbeing.37

The caregiver burden must be considered, due to the constant need to provide care, co-ordinate resources, plan activities, and manage behavioural and mobility difficulties when looking after an individual with DS or LGS.16,46 Caregivers also report a personal impact on sleep, social activities, relationships, working capacity, and their mental health.37,46,47 Of note, though, in one survey, parents discussed how caring for a child with LGS had some positive aspects. This included making them stronger and more compassionate, helping them develop patience and understanding, learning that they can be an advocate for their child, showing that every child has goals and things they attain, and making them realise they were more resilient than they thought they were.47

There is also a financial burden for people with DEEs and their families, through both direct costs around the patient, and indirect costs, such as loss of earnings.16,29,37,46-48 One survey highlighted that most respondents said caring for an individual with DS impeded employment, with 45% of respondents having quit, retired from, or lost their jobs due to caregiving, and others having to switch jobs.46 Work impacts, a survey of caregivers of an individual with DS showed, were more predominantly found in mothers (50.0%) than fathers (7.1%). The study concluded that mothers bear a greater burden of childcare than fathers.48

Measuring Non-Seizure Symptoms

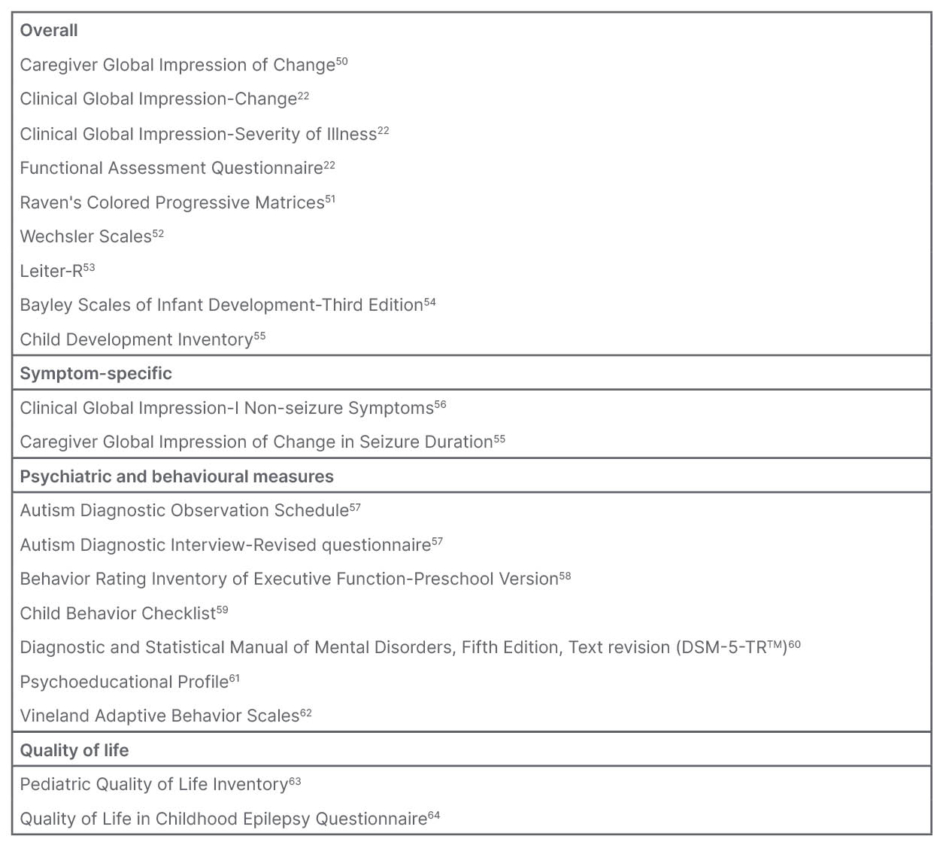

To enable optimal interventions for individuals with DS and LGS, Cross discussed the need for early assessment of NSS. However, in clinical practice and trials there can be problems with objectively measuring NSS, due to patient heterogeneity, the demand for short-term outcomes, and the inability of some scales to measure change over time. Valente argued the need for the multi-informant and multi-assessment caregiver- and clinician-administered batteries of tests, including measures of motor, medical, and psychiatric comorbidities (Table 1), due to limitations in standardised instruments and direct assessment methods.49

Table 1: Examples of rating scales utilised in clinical settings for people with Dravet syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

DSM-5 is a registered trademark of the American Psychiatric Association.

“You have to find the best possible way to assess [NSS],” stressed Valente, “because if you don’t, you may jump to the wrong conclusions.” For example, in one clinical trial of a treatment for people with DS, while Caregiver Global Impression of Change (CGIC) scores showed improvement, Vineland composite standard score and HRQoL measures did not change.50 In another trial, of an anti-seizure medication (ASM) for people with DS, although PedsQL total score was significantly higher compared to baseline, showing that it may be useful to address HRQoL, another measure of overall HRQoL did not show significant changes.65

Using combined measures, said Valente, can increase the specificity and sensitivity of measuring NSS. For example, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) is considered a gold standard assessment, with high sensitivity and specificity, when assessing autism spectrum disorder.66 However, in DEEs, said Valente, limitations of ADOS include that it is less applicable to people who are non-verbal, have motor and sensory impairments, and have severe intellectual disabilities, as may occur in individuals with DS or LGS.

As an example of the benefits of a more comprehensive assessment, one study in children with DS57 combined results from the ADOS (observational assessment applied by the healthcare provider with expertise) with a structured parents’ interview (the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised questionnaire [ADI-R])52 and a psychiatric clinical interview following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text revision (DSM-5-TRTM) criteria.60 In addition, the authors used the Psychoeducational Profile,61 the Child Development Inventory,55 and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II) questionnaire.62 The authors concluded that a more specific autism spectrum profile with relative preservation of social skills may explain possible underdiagnosis of autism spectrum in people with DS, and can be used to establish early adapted rehabilitation programmes that include NSS care needs.57

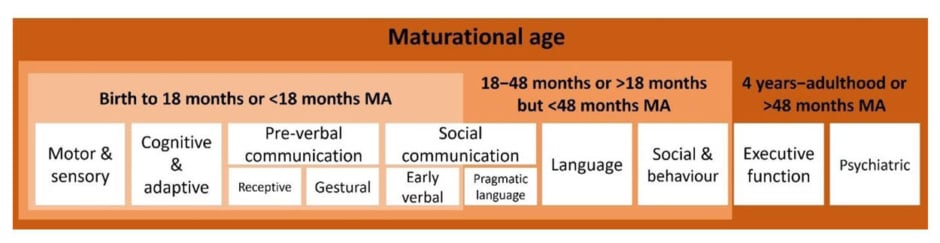

Valente also discussed the need for adapting questionnaires and scores to encompass the needs of individuals with DEEs. For example, to better match the individual abilities of an adolescent with a DEE, instruments developed for a much younger age group may be needed to assess maturational age rather than chronological age (Figure 2).49,67 Another adaptation is using measures that have been developed for other conditions that share some similarities with NSS. For example, in one study, instead of just noting presence/absence of communication skills, a validated measure for cerebral palsy was used, that rates communication using number of words and length of sentences a child typically uses, and whether communication was primarily via speech or gestures. This measure provided a more comprehensive view of the level and type of developmental delay, with regard to communication in individuals with DS or LGS.18

Figure 2: Domains needed to be assessed in non-seizure symptoms can be adapted outside their

intended age range.49,67

MA: maturational age.

Valente also discussed how scores should be tracked and compared over time for the individual, and not compared to standard developmental scores, where a person’s abilities may be seen to decrease over time, even if, within themselves, they have made gains.68 In this sense, the use of raw scores and subdomains can help guide individualised therapy.

Further, Valente talked about the need for adaptations of disease-specific measures for LGS and DS. For example, general sleep questionnaires may lack questions regarding seizures during sleep, the impact of ASMs on sleep, sleepwalking, enuresis, co-sleeping with parents, and sleeping away from home.38

Examples of measures designed for specific conditions include the ‘Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 deficiency disorder Severity Assessment,’ which includes tailored domains for motor, vision, speech, cognition, behaviour, and autonomic function impairments,69 and the ‘neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 Clinical Rating Scale,’ which has condition-specific motor and language domain scoring, and has been used to help track the utility of a drug therapy over time, but may not be feasible to all DEEs.70 In this context, adaptations of current metrics that have already been validated over the last decades are of interest.

One measure that has been adapted specifically for DS and LGS is the Clinical Global Impression-I Non-Seizure Symptoms (CGI-NSS) measure. This measure assesses communication, alertness, and disruptive behaviours, and can be used to compare an individual’s progress over time, as opposed to against standard scores.56 There is currently a need, discussed Cross, for associated groups and regulatory authorities to validate and accept such disease-specific measures, and for natural history studies to test that the baseline against which such measures are used is relevant. Valente also stressed how appropriate non-seizure metrics should be incorporated into clinical trials for DEEs, that may include non-standard measures using an individualised approach.

Impact of Current Management and Future Perspectives for Non-seizure Symptoms

When caregivers have been asked to rank the NSS aspects of DS they wanted to see alleviated by therapy, responses included language and communication (72−83%), sleep issues (67%), gross/fine motor function difficulties (64/61%), executive function issues (61%), and behavioural concerns (53%). Other therapy needs included emotional, social, and feeding difficulties (19−44%).17

Although the standard treatment for seizures in DEEs is an ASM, some are contraindicated for some individuals with DS, as they are linked to more severe and frequent seizures,31 and steeper cognitive decline.71 One review of ASMs in people with DEEs also found negative effects of some on behaviour, mood, cognition, sedation, and sleep.72

Treatment specifically for NSS may include the management of cognitive and behavioural difficulties, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy. Non-pharmacological treatments for seizures, such as a ketogenic diet and vagus nerve stimulation, may also positively impact NSS if these result in seizure reduction.7,23,29 Drugs used for comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as newer generation antidepressants, appear to have a tolerable safety profile, and do not lower seizure threshold.27 Psychological strategies, such as mindfulness therapies and cognitive behavioural therapy, may also be beneficial for some NSS.73 However, in one study, while nearly two-thirds of 46 children with epilepsy met diagnostic criteria for a mental health condition, two-thirds of these had not received any support for such comorbidities. Where treatment was offered, it was highly variable, from a defined number of sessions to ongoing support.74

One intervention, for which Cross is co-chief investigator, is in the Mental Health Intervention for Children with Epilepsy (M.I.C.E.) trial, which adds telephone-delivered therapy to standard assessment and care. Here, healthcare professionals are trained to deliver the ‘Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma or Conduct problems (MATCH-ADTC)’ intervention, which is based on cognitive behavioural therapy, for managing behaviour and psychological problems. In a randomised controlled trial of MATCH-ADTC versus usual care of children with epilepsy-associated behaviour problems, the MATCH-ADTC cohort showed greater improvement in Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire scores after 6 months than the usual care cohort. Benefit was sustained after 12 months. This trial has demonstrated the real possibility of an intervention delivered by trained non-specialists offering benefit to children with DEEs.75

Conclusions

Along with the burden of seizure symptoms in people with DS and LGS, the impact of NSS, which can be due to multifactorial reasons, can be widespread. NSS occurrence necessitates the use of multidisciplinary teams, to both assess and track such symptoms from first diagnosis of DS or LGS, as well as to provide individualised therapy. Key is the need to improve accuracy of NSS measurement, and for early assessment.15,21,27-29,34 Due to bidirectional features of NSS and comorbidities, treating these may also positively impact seizures; however, studies are still needed to examine any such therapeutic relationships.27,34 There is often also considerable caregiver burden, so caregiver support is also essential.16,29,37,46,47