INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) predisposes the patient to recurrent episodes of acute painful haemolytic crisis. Sickle cell nephropathy is not uncommon in adult patients, and renal manifestations of sickle cell nephropathy include renal ischaemia, microinfarcts, renal papillary necrosis, and renal tubular abnormalities with variable clinical presentations.1-4 Intravascular haemolysis and reduced glomerular filtration rate with renal tubular dysfunction predispose to true hyperkalemia.3,4 Haemolytic crisis can be complicated by sepsis, leading to significant degrees of thrombocytosis, and thrombocytosis is a well-defined cause of pseudohyperkalaemia.2 The authors have described a 40-year-old African American male patient with sickle cell anaemia who exhibited alternating episodes of true hyperkalaemia and pseudohyperkalaemia, during the same hospitalisation.5 Clearly, true hyperkalaemia is a potentially lethal condition. Simultaneously, the institution of inappropriate and intensive treatment of pseudohyperkalaemia leading to severe hypokalaemia is also potentially lethal.6 The need for this caution is most imperative with the recent introduction of the safer, more potent potassium binders, patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (SZC).7

METHODS AND CASE REPORT

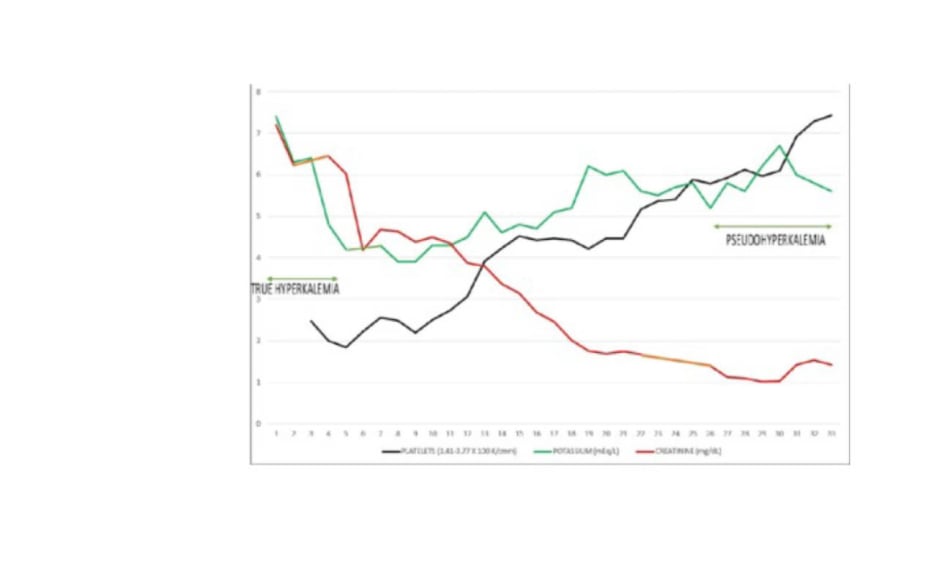

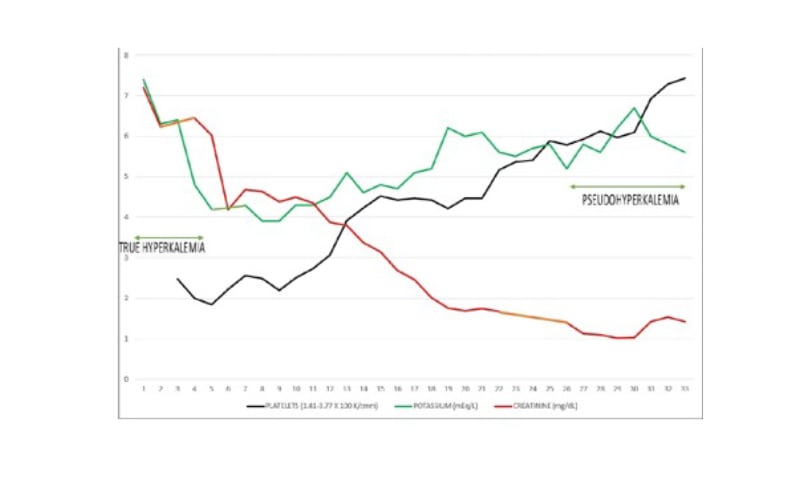

The authors described a 40-year-old African American male patient with sickle cell anaemia who exhibited alternating episodes of true hyperkalaemia and pseudo-hyperkalaemia during a single hospital admission.5 Admission true hyperkalaemia was accompanied by haemolytic crisis, sepsis, high anion gap metabolic acidosis (serum bicarbonate <5 mmol/L), and acute kidney injury. About 2 weeks into the admission, with normalised kidney function, he had demonstrated persistently elevated serum potassium levels, which persisted despite the addition of diuretics and daily SZC. An incidental normal ECG, despite a measured serum potassium of 6.7 mmol/L, led to the consideration of pseudohyperkalaemia. Simultaneous plasma potassium returned to be much lower than serum potassium, thus confirming pseudohyperkalaemia. The pseudohyperkalaemia was ascribed to severe thrombocytosis complicating sepsis (Figure 1). Subsequently, SZC was discontinued and the patient was soon discharged home without any further complications.

Figure 1: Simultaneous trajectories of serum potassium, serum creatinine, and platelet count during the hospital admission.

DISCUSSION

Pseudohyperkalaemia, first reported in 1955 by Hartmann and Mellinkoff,8 is a marked elevation of serum potassium in the absence of clinical evidence of electrolyte imbalance. Simultaneous serum potassium exceeds plasma potassium by >0.4 mmol/L.9 Pseudohyperkalaemia has mostly been associated with moderate to severe thrombocytosis or leukocytosis.10 Unmistakably, true hyperkalaemia is potentially lethal. Nevertheless, inappropriate treatment of pseudohyperkalaemia leading to severe hypokalemia is also life-threatening.6 The authors believe that this is the first report of adult SCD demonstrating alternating cycles of true hyperkalaemia and pseudohyperkalaemia at different times during the same hospitalisation. It is imperative to draw attention to the new potassium binders, patiromer and SZC.5 The authors advocate caution in the use of these potent potassium binders and to always give consideration to the presence of pseudohyperkalaemia under appropriate clinical scenarios. They posit that those providers treating patients with SCD must be aware of such a phenomenon to avoid the dangers of overtreatment of episodes of pseudohyperkalaemia.5 One recurring mantra remains true most of the time: true hyperkalaemia in the absence of overt kidney dysfunction must always be viewed with circumspection and doubt. Iatrogenic, life-threatening hypokalaemia remains a real concern and must be avoided.5