Meeting Summary

People with HIV (PWH) living in the modern antiretroviral therapy (ART) era, many of whom are now over the age of 50 years, may experience weight gain and excess visceral abdominal fat (EVAF), which are all linked to increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. While BMI is proposed as a means to gauge CVD risk, this may not be appropriate in PWH who have EVAF. Previous analysis of data from the Visceral Adiposity Measurement and Observations Study (VAMOS), which included 170 PWH taking ART with a BMI between 20−40 kg/m2, revealed a relationship between EVAF and both the overall and components of the America College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) 10-year atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk score. In this poster presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) 2025, nearly half of the participants with a ‘normal’ (20−25 kg/m2) or ‘overweight’ (25−29 kg/m2) BMI had EVAF (visceral adipose tissue [VAT] surface area ≥130 cm2), as measured by CT scan. The vast majority of participants with BMI 30−40 kg/m2 also had EVAF. ASCVD risk score level was significantly higher in participants with ‘high’ EVAF compared to low EVAF (VAT surface area <130 cm2), regardless of having a BMI above or below 30 kg/m2. Pericardial fat volume was also significantly related to high EVAF, with a strong correlation with increasing VAT surface area but a weaker correlation to subcutaneous fat surface area. These findings highlight the limitations of BMI alone as a surrogate for ASCVD risk in PWH and the need to include EVAF screening to help identify CV risk in PWH.

Introduction

There are over 1 million people living with diagnosed HIV in the USA,1 with their life expectancy greatly extended due to modern ART.1-4 Accordingly, nearly three-quarters of this population is projected to be over the age of 50 years by 2030. PWH can experience substantial weight gain and long-term obesity, which may lead to ‘critical health risks’, potentially due to increased metabolic inflammation associated with HIV.5,6 Indeed, there is an increased risk of CV-associated conditions in PWH, including heart failure,7-9 coronary artery disease,10 and myocardial infarction.11 This is regardless of risk factors such as age, diabetes, substance abuse, and hypertension, as well as BMI.8,10,11

While BMI has been proposed as a quick and easy way to gauge risk of CVD and associated comorbid disease, 12 this may not be appropriate in PWH with central adiposity.13 Ectopic fat deposition, known as visceral fat, is one of the most important factors predisposing individuals to cardiometabolic complications (e.g., diabetes, coronary artery disease, fatty liver) and other comorbidities. EVAF is hard to evaluate, not routinely measured in clinics, and may or may not be associated with obesity.14 It is, therefore, of interest to understand the relationship between BMI, EVAF, and CVD risk factors for PWH receiving ART. This will help evaluate whether BMI fully addresses the risk for this population.

The cross-sectional, multi-center observational study known as VAMOS included PWH who were virologically suppressed on ART for at least a year and had a BMI between 20−40 kg/m2. Previous analysis of VAMOS data showed a relationship between EVAF and the overall 10-year ASCVD risk score. There was also a relationship with several components of the risk score, including increases in total cholesterol (TC), systolic blood pressure, and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, along with decreases in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C). Increased triglyceride (TG) levels and subsequent increases in the TG:HDL ratio were also found. Analysis also indicated a small relationship between increasing visceral adipose tissue area and reductions in growth hormone, which helps regulate lipid metabolism, body fat distribution, and vascular health.15,16

The Relationship Between Excess Visceral Abdominal Fat and BMI

This VAMOS evaluation presented at CROI 2025 included 170 participants with a mean age of 54 years, assessed in 2023. Of these participants, 89% were male, and 70% were White. EVAF, defined as VAT surface area ≥130 cm2, was quantified via CT abdominal scan at L4-5 vertebrae. Pericardial fat volume was also calculated via CT scan. CV risk was evaluated by 10-year ASCVD risk score, which is calculated based on age, race, blood pressure, TC, HDL-C, and low-density lipoprotein, alongside diabetes, smoking, and medication history.17 Measurements were taken in the overnight fasting state, with CT and lab measurements paired for all participants.

Overall, EVAF was found in a considerable number of participants. Notably, while incidence was 47% in those considered ‘overweight’ by BMI standards (n=36; 25−29.9 kg/m2), 88% in those considered ‘obese’ (n=35; 30−34.9 kg/m2), and 69% in those considered ‘extremely obese’ (n=11; BMI: 35−40 kg/m2), EVAF was also shown in 43% of participants with a BMI considered to be ‘normal’ (n=16; 20−25 kg/m2).

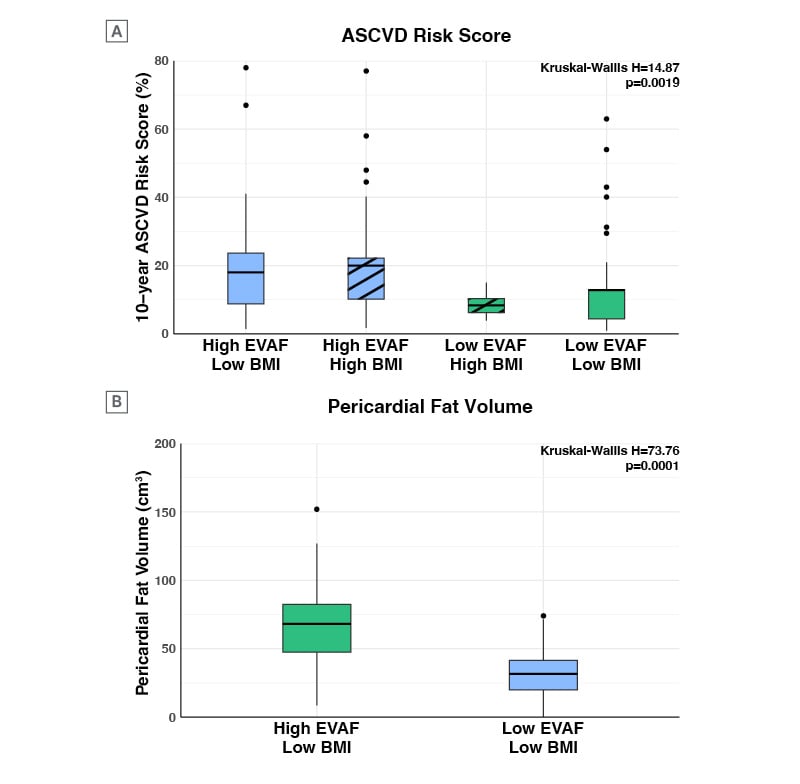

For analysis of how EVAF and BMI relate to ASCVD risk score (using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s tests), four distinct groups were identified (Figure 1): High EVAF (≥130 cm3) with either ‘low’ (20−29.9 kg/m2; n=52) or ‘high’ (30−50 kg/m2; n=46) BMI, and Low EVAF (<130 cm3), also with either ‘low’ (n=10) or ‘high’ (n=62) BMI.

Figure 1: Higher cardiovascular risk and pericardial fat volume in people with HIV with high excess visceral abdominal fat.

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; EVAF: excess visceral abdominal fat.

As shown in Figure 1A, when the groups were compared, levels of 10-year ASCVD risk score were significantly higher in participants with high EVAF compared to groups with low EVAF (χ²(3)=14.87; p=0.0019), irrespective of high or low BMI status. Also found (Figure 1B) was that in participants with low BMI, pericardial fat volume was significantly higher in those with high EVAF, compared with those with low EVAF (χ²(3)=73.76; p<0.0001).

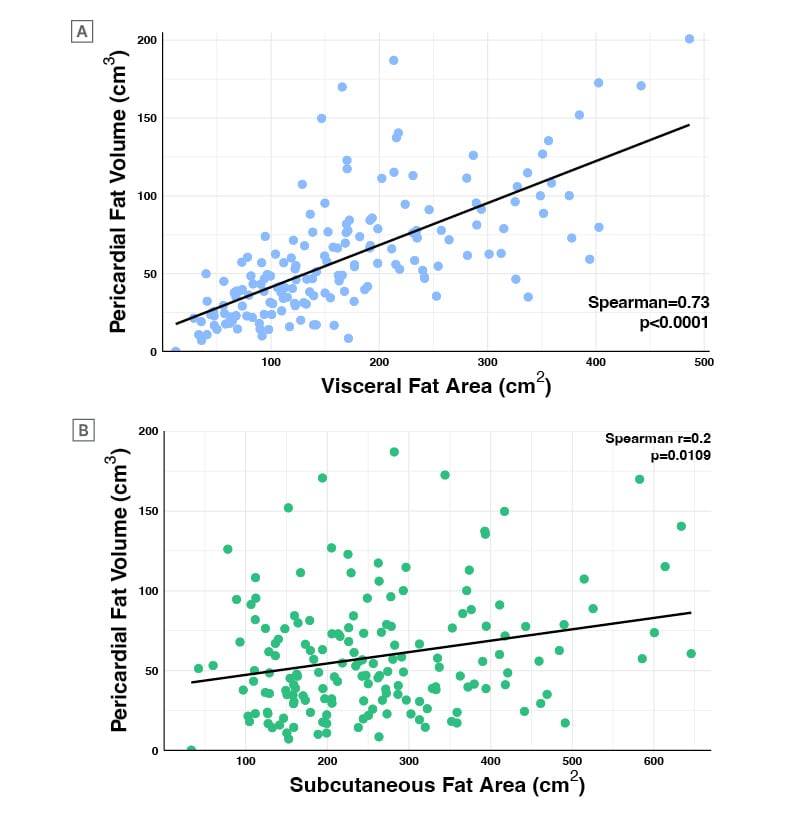

Next, Spearman correlation showed that increasing visceral abdominal fat surface area was strongly correlated with pericardial fat volume (Spearman r=0.73, p<0.0001) (Figure 2A). There was a positive but weaker correlation between subcutaneous fat surface area and pericardial fat volume (Spearman r=0.20, p=0.0109) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2: Visceral abdominal fat area has a stronger correlation with pericardial fat volume than subcutaneous fat area in people with HIV.

Conclusion

The latest International Antiviral Society-USA Panel guidelines stress the need to regularly assess weight and anthropometric measurements (e.g., waist circumference) and screen for diabetes and CVD in PWH taking ART, especially if they have a higher 10-year ASCVD risk.18 EVAF has been linked to CVD and cardiometabolic syndrome risk,14 with studies in men with HIV also finding this relationship.19,20 These findings highlight the limitations of utilizing BMI alone in assessing CV risk among PWH, particularly among those with normal or overweight BMI. Incorporating tools to assess EVAF, such as waist circumference, could provide critical information in identifying PWH at risk of CVD.