BACKGROUND

Febrile neutropenia (FN) is a common complication in patients with cancer, and historically, pseudomonal infections have been attributed to significant morbidity and mortality in this group of patients.1,2 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for FN in patients with cancer recommend the initiation of an empiric anti-pseudomonal (PsA) antibiotic (abx), based on patient risk factors, with recommendation for modification of initial regimen based on microbiologic data obtained throughout the course.3 At Olive View-University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center, Sylmar, USA, the authors reviewed FN cases to determine the prevalence of PsA bacteremia and assess the necessity of anti-PsA abx.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

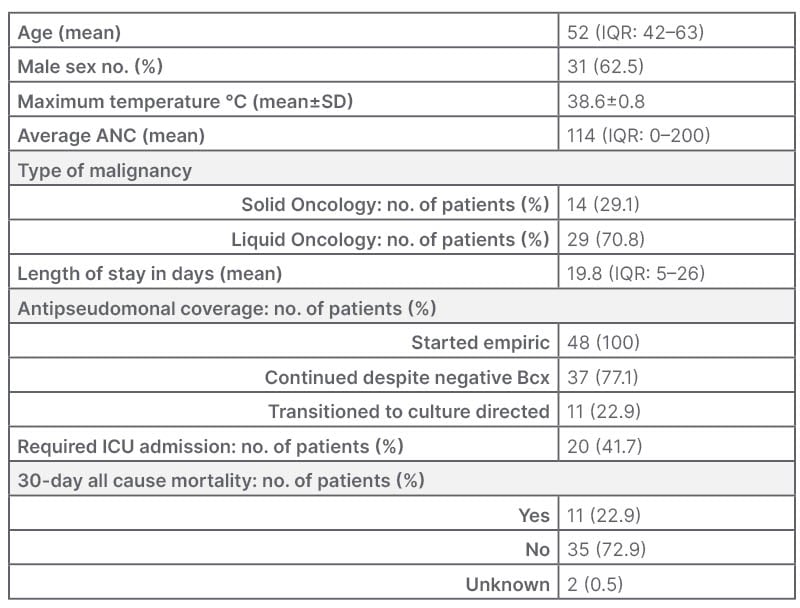

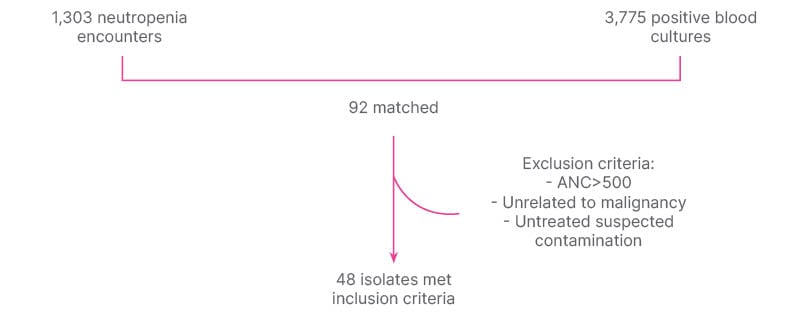

Single center retrospective chart review on all positive blood cultures (Bcx) from January 1, 2017–December 30, 2022. Positive Bcx were matched with ICD-10 codes for neutropenia on inpatient encounter (Table 1). Exclusion criteria consisted of absolute neutrophil count >500, FN not related to malignancy, and untreated suspected contamination (Figure 1). Charts were reviewed for Bcx results, source of bacteremia, antibiotic prescribing, 30-day all-cause mortality, and risk factors for PsA infection.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics.

Three patients with >1 encounter for neutropenic fever.

ANC: absolute neutrophil count; Bcx: blood cultures; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; no.:

number; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1: Methods.

ANC: absolute neutrophil count.

RESULTS

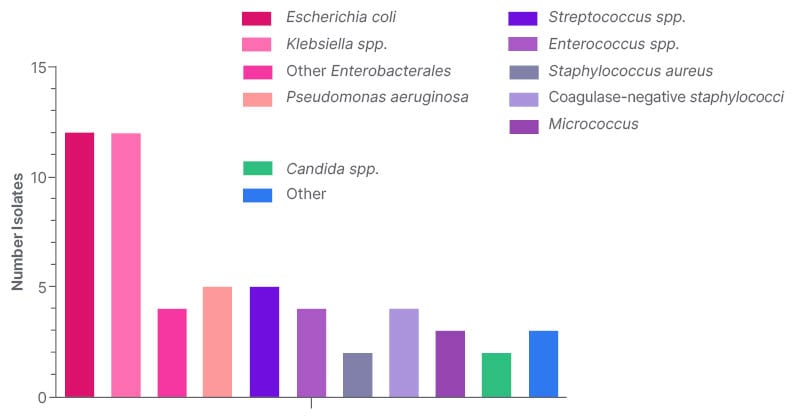

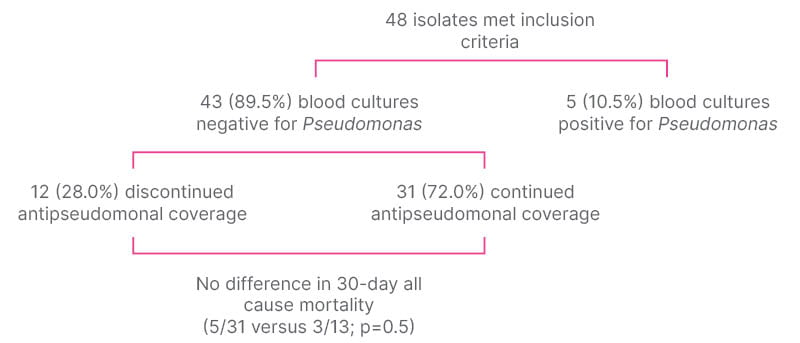

Of 1,303 neutropenia encounters and 3,775 positive Bcx, 92 were matched, and 48 met inclusion criteria. The most common source of bacteremia was intra-abdominal (n=17; 35.4%), followed by line-associated infection (n=9; 18.8%). Gram-negative bacteremia was slightly more common than gram-positive, with Enterobacterales found in 28 (58.3%) and PsA found in five (10.4%; Figure 2). All 48 cases were started on empiric anti-PsA abx, and 31 (64.6%) were continued on anti-PsA abx for an average of 11 days (interquartile range: 5–14) despite no isolated PsA in the blood. Thirty-day all-cause mortality was not significantly different between those who continued on anti-PsA abx versus those in whom anti-PsA abx were stopped when PsA was not isolated (5 out of 31 versus 3 out of 13; p=0.5; Figure 3). All cases of PsA bacteremia had at least one risk factor for nosocomial acquisition, e.g., hospitalization and/or abx exposure within prior 30 days.

Figure 2: Prevalence of bacteremia based on organism.

Figure 3: Prevalence and outcomes of Pseudomonas bacteremia.

CONCLUSION

The most common organism causing bacteremia in FN was Enterobacterales. The prevalence of PsA bacteremia was low, yet most were continued on anti-PsA abx despite Bcx showing a different organism. Continuation of anti-PsA abx did not make a difference in 30 day all-cause mortality when PsA was not isolated. When it occurred, the most common risk factor for having PsA bacteremia was hospitalization within the prior 30 days, with exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics. This suggests that although anti-PsA antibiotics are routinely given empirically to this patient population, the need is low if the patient is from the community/home and has had no healthcare exposure. PsA is not felt to be normal bowel/body flora in a non-hospitalized or antibiotic-exposed patient. Thus, patients may be risk stratified for PsA as part of an antibiotic de-escalation strategy, and further stewardship efforts can be focused on de-escalating anti-PsA antibiotics, especially when not isolated from cultures.