Abstract

Regenerative medicine is an exciting field of research, in which significant steps are being taken that are leading to the translation of the technique into clinical practice. In the near future, it is expected that clinicians will have the opportunity to bioprint tissues and organs that closely mimic native human tissues. To do so, imaging of patients must be translated to digital models and then fabricated in a layer-by-layer fashion. The main aim of this review is to elaborate on the possible mechanisms that support four-dimensional bioprinting, as well as provide examples of current and future applications of the technology. This technology, considering time as the fourth dimension, emerged with the aim to develop bioactive functional constructs with programmed stimuli responses. The main idea is to have three-dimensional-printed constructs that are responsive to preplanned stimuli. With this review, the authors aim to provoke creative thinking, highlighting several issues that need to be addressed when reproducing such a complex network as the human body. The authors envision that there are some key features that need to be studied in the near future: printed constructs should be able to respond to different types of stimuli in a timely manner, bioreactors must be developed combining different types of automated stimuli and aiming to replicate the in vivo ecology, and adequate testing procedures must be developed to obtain a proper assessment of the constructs. The effective development of a printed construct that supports tissue maturation according to the anticipated stimuli will significantly advance this promising approach to regenerative medicine.

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that the replacement or regeneration of organs due to accidents or disease continues to be a worldwide problem. Indeed, transplantation is insufficient1 and is associated with very high costs, while requiring a high level of specialisation from healthcare professionals. Furthermore, several limitations to transplant can arise, including the lack of compatible donors, a high incidence of transplant rejection, and morbidity implications for the living donor.2 Regenerative engineering has come to be considered an inevitability and a promising approach for the regeneration of tissues or organs by culturing patient cells into biological substitutes (scaffolds) and subsequent implantation into the patient for the regeneration of new tissue.3 These scaffolds can be produced by different approaches, usually referred to as conventional or nonconventional techniques. Although both of these categories have advantages and drawbacks, the nonconventional procedures, usually three-dimensional (3D) printing, may provide significant advancements for obtaining optimised, tailored constructs.4 Using an additive manufacturing process, nonconventional procedures suitably control pore size, geometry, and spatial distribution, and guarantee pore interconnectivity, which are key features for successful tissue regeneration.5

Most of the original bioprinting techniques were developed to produce two-dimensional (2D) constructs; however, tissue maturation in such culture substrates can significantly differ in morphology, cell–cell interactions, and cell–matrix interactions, contrasting to 3D environments.6 Accordingly, significant efforts have been made to translate 2D bioprinting techniques to 3D aptness. Currently, it is possible to manufacture 3D implants with customised features: biodegradable or permanent, with or without cells, and with or without surface functionalisation, among others. These advantages permit researchers to optimise the manufacturing process, aiming for full automation, while studying the most adequate approach for the intended application. Traditionally, the manufacturing process begins with a 3D digital model (using computer-aided design tools) that is sent to a 3D printer to produce the model in a layer-by- layer fashion. Different processes (e.g., jetting, fusion, sintering, and melting) and various materials (e.g., polymers, ceramics, and metal) can be used in a hybrid manner, providing noteworthy developments for obtaining enhanced tailored scaffolds.7

One of the most common procedures in regenerative medicine is the manufacture of 3D scaffolds, which are posteriorly seeded with cells. Ideally, when this scaffold is implanted into the body it should degrade in a timely manner and be completely compatible with the neotissue ingrowth.8 In opposition, bioprinting refers to the processes of patterning and assembly of living and non-living materials at once.9 Bioprinting is intended to produce scaffolds that are able to instruct or induce the cells to develop into a tissue mimetic or tissue analogue structure, for instance, by hierarchical induction of differentiation.10 To do so, the topological and biological properties should lead to a tailored construct that permits tissue development.5 Thus, to print adequate constructs for promoting homogenous cell proliferation and/or differentiation, a clear understanding of the advantages and drawbacks of each technique and biomaterial or bioink is critical.3 However, 3D bioprinting has been used for the production of implants that fail to mimic native live tissues: they have no ability to acutely change according to the functional status and changes in the environment.11 This was the main reason for the development of four-dimensional (4D) bioprinting, with the foundational works developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.12 With the fourth dimension referring to time, the aim of 4D bioprinting is to promote dynamic changes of the construct, improving its functional response. It emerged as a technology with the ability to induce planned changes of the constructs, bridging the gap between the laboratorial constructs and the native human tissues. The procedure involves a 3D construct that can change its properties (e.g., shape) under a predesigned stimulus to develop biologically active constructs.13 To do so, different types of stimuli can be used, making it suitable for various regenerative medicine applications. The potential of 3D printing enhanced by a fourth dimension makes it possible to contribute significantly to the bioprinting of engineered tissues, such as the liver14 and heart,15 which will represent a major breakthrough in the area of regenerative medicine.16 For this review, only the shape-morphing capabilities of 4D bioprinting were considered

EXISTING MECHANISMS OF FOUR-DIMENSIONAL BIOPRINTING

In the 4D bioprinting process, different printing technologies, biomaterials and bioinks, and stimuli can be used. Each one of these elements must be specifically tuned for the type of biological construct to be produced. The most commonly used techniques for the printing process can be divided into three categories: jet-based, extrusion-based, and laser-assisted.17 Jet-based methods produce a jet of small droplets of a liquid material, extrusion-based printing consists of a robotically controlled dispensing system to extrude a material in a continuous way, and laser-assisted methods use laser energy for material curing according to its absorbing capacity.4,7 Both the materials to be used as well as the aimed architecture must be previously defined before choosing the printing technique(s). The materials must also be automated to respond to the desired stimuli: they should have mechanical stability closely mimicking the structure of native tissues, printability features that allow the desired resolution (size), and biocompatibility. With the currently available technologies, adjustment among these abilities must be made because no technique can fulfil all of these characteristics.10

Regarding the biomaterials, studies have demonstrated the potential of using synthetic and natural polymers for scaffold production.18,19 On one hand, natural polymers can closely mimic the native environment, providing adequate signalling for cell guidance,20 but these materials are often difficult to process. On the other hand, synthetic polymers offer a wide range of chemical compositions and processabilities.21 However, the most limiting factor for successful 4D bioprinting is the living cells22 since they need the material to be cell adhesive, biocompatible, non-toxic, and biodegradable (at a certain degradation rate).

Accordingly, one specific area of bioprinting that is attracting great interest is the use of hydrogels as bioinks. Due to their capability for absorbing and retaining large quantities of water, hydrogels support a wide range of viable cells, growth factors, and/or genetic material while being extruded from a syringe nozzle. They are currently the most widely used scaffold material in 3D printing due to their easily controlled functionality, without the complex synthesis steps required to replicate the native biological tissue’s physiochemical properties.23,24 Nevertheless, they must meet certain requirements, in addition to their cell culture suitability, to be considered for bioprinting. High temperatures, organic solvents, shear force-generated stress, and exposure to ultraviolet light are examples of conditions that can damage the cells during the printing process.1 Cells should be selected according to their high viability and yield, limited harvesting-associated morbidity, robustness and mechanical resilience, limited immunogenicity, and extended trophic properties.

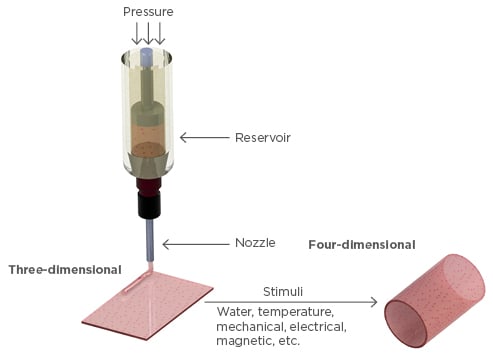

Planned stimuli can change the material’s wettability, phase transition, swelling or shrinkage, softening, magnetic and electrical permeability, optical properties, and molecular and ionic interactions.25 Moreover, they can also change these various properties in the same composite, making the structure suitable to change into different shapes and functions for innumerable purposes. 4D bioprinting technology brings material science, biology, and chemistry together to create new ‘smart’ materials that can incorporate both cells and bioactive molecules; actively modulate cellular behaviours,26,27 including adhesion, proliferation, migration, differentiation, and maturation; and maintain cell viability and function, all while having good printability and shape fidelity. Responsive biomaterials are being developed at a fast pace. Humidity,28,29 temperature,30-33 electric,26,34,35 magnetic,36 molecular,37,38 and light-responsive27,39 biomaterials and bioinks are being created with single and multishape transformation capabilities. With this ability, a rectangular construct can transform itself into a hollow tube (Figure 1) with a programmed diameter and a patterned architecture, incorporating different cell types and orientations to meet the needs of the tissue or organ being mimicked.40,41

Figure 1: Illustrative representation of the transformation from three-dimensional to four-dimensional bioprinting, which can be triggered by different types of stimuli.

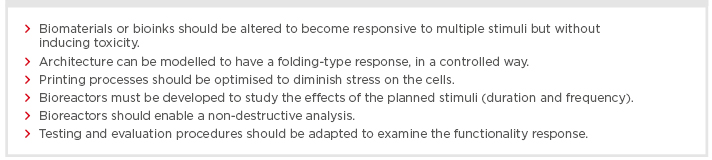

After printing the construct, a critical challenge is to maintain cell viability and impose upon the cells the desired differentiation and maturation. Devising and developing tailored bioreactors capable of mimicking the physiological scenario and of replicating the nutrient transport through blood flow in the human body is the ultimate goal.13 Additionally, the fluid-flow regime, the environmental control (oxygen levels, pH, temperature, and metabolite control), the stimulation (culture medium, growth factors, and stimulus), and their influence on cellular behaviour are the most important parameters to control for each type of tissue.42 The development of new bioreactors with embedded sensory elements and imaging could guarantee real-time control of the process and enable automated feedback. Accordingly, the authors envision that systems able to withstand different types of stimuli (e.g., mechanic-like rotating, confined, or sliding compression/tension) to simulate native tissue loads and impacts, or to induce directional orientation (e.g., electric/magnetic), are the future of bioreactors.43,44 Independent of the mechanism used or its exact definition, 4D bioprinting has the potential to turn organ printing into a reality in the coming years. Combining engineering with life sciences, regenerative engineering may closely replicate the path of biological development (Box 1).

Box 1: Regenerative engineering may closely replicate the path of biological development.

CURRENT APPLICATIONS OF FOUR-DIMENSIONAL BIOPRINTING

In recent years, major progress has been made in the development of smart materials suitable to be used in regenerative medicine.45 While smart materials have been produced by several methods, making them suitable to be bioprinted is an intricate process. In accordance, some experiments have been conducted demonstrating shape-morphing materials but not their applicability. The studies demonstrating their applicability have commonly only involved non-living materials and, thus, are not considered examples of bioprinting.9

Composites able to respond to water stimulation have been of high interest in recent years because water is a major constituent of the human body.16 Gladman et al.46 developed a biomimetic 4D printing method inspired by botanical systems. Through the control of printing parameters, such as filament size, orientation, and interfilament spacing, the researchers created mesoscale bilayer architectures. These had programmable anisotropy that morphed into given target shapes on water immersion. Although an interesting approach, further developments on its usefulness for tissue engineering are lacking.

One of the most interesting approaches is the use of 4D bioprinting to obtain prevascularised structures, since vascularisation is a key issue to be addressed when engineering various types of functional tissues.16 4D-printed constructs can be manufactured as layer-by-layer solids, mixing the cells and hydrogels to obtain cylindrical structures like the blood vessels.47 These hydrogels laden with cells can be activated by maturation factors, leading to rapid vascular cell maturation; however, available bioprinters have a characteristic ability to produce tubes that are tens to hundreds of micrometres in diameter, a resolution far from the native size of human blood vessels. Recently, 4D bioprinting was used to produce vessels with an average internal diameter of 20 µm.37 The investigators printed a flat surface, which, when stimulated, folded to a well-defined tube. As the materials used (alginate and hyaluronic acid) did not pose any negative effect on the viability of the printed cells, this may be a promising approach to reduce the internal diameter of the constructs.

One condition that remains fairly stable in the human body is a physiological temperature of around 37°C. Hence, thermoresponsive materials created and stored at different temperatures may change properties upon implantation.33,48 The sensitivity to temperature relies on the balance between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments of the material.49 Upper or lower critical solution temperatures will interrupt the electrostatic interactions, leading to a collapse or expansion of the material.50 Among the developed thermoresponsive materials, poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) is the most studied for regenerative medicine purposes. The low critical solution temperature (~32oC) and the good biocompatibility were useful for tailoring suspension rheology.51 Promising results were also obtained for the use of shape-memory polyurethane to print 4D scaffolds.48 The seeded cells were significantly more elongated after shape recovery, demonstrating high potential to be applied in diverse clinical contexts. Lastly, it is understood that some diseases induce changes in body temperature; thus, thermoresponsive polymers may be a useful tool for diagnostic purposes.50 With regard to thermoresponsive hydrogels, Cochis et al.52 used methylcellulose for cell-sheet engineering. After optimising the printing process parameters, methylcellulose hydrogel rings were extruded for the first time. Cell orientation was observed for the ring-shaped cell-sheet and confirmed by the more elongated cell nuclei than those in sheets detached from the bulk hydrogels.

Both bone and cartilage regeneration are specific targets attracting a lot of interest from research groups worldwide. Significant improvements to bone and cartilage regeneration have been achieved by developing 3D-printed implants,3,53,54 and incorporating the fourth dimension may control the properties of surfaces, enabling the adsorption or desorption of molecules and cells. Regarding the materials, a novel, renewable soybean oil epoxidised acrylate has demonstrated the ability to fix a temporary shape. Accordingly, by 3D laser printing, researchers produced smart and highly biocompatible scaffolds capable of supporting the growth of multipotent human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells.31 Regarding the process, by applying a straightforward magnetic–based mechanism in hydrogels during bioprinting, it was possible to align collagen fibres in less concentrated hydrogel blends.55 After 21 days of culture, the controlled constructs expressed more collagen II than the randomised constructs. These two examples highlight that both the material and the process should be further developed to enable their use for tailored implants.

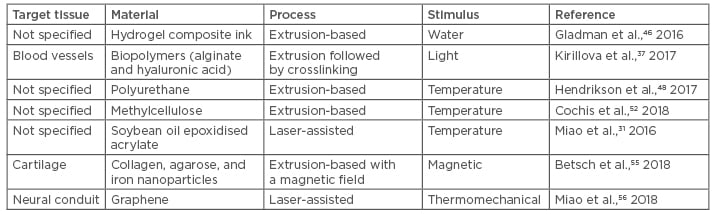

Although some applications have been demonstrated (Table 1), research efforts have not extended beyond the initial proof-of-principle phase.57 Without reports illustrating the performance of a 4D-printed implant, there is a long way to go to get closer to translational medicine in regenerative engineering. Most of the available studies in the literature do not focus on a specific type of tissue regeneration; however, the medical community is at the point of developing bioinks that have the ability to respond to stimuli, with their usefulness still to be investigated.

Table 1: Examples of current applications of four-dimensional bioprinting.

CONCLUSION

Despite the current advances, there is still a long way to go to achieve bioactive 4D structures that are able to mimic human tissues, in part because most developed materials are responsive to only one type of stimulus, whereas the human body relies on complex physiological networks. Further understanding of how the current constraints limit the desired translation will promote investigation of future 4D bioprinting applications. The interdisciplinary combination of life sciences with engineering is demonstrating noteworthy advances for healthcare. Although 3D bioprinting has opened minds to biofabrication, the absence of response to planned stimuli should be considered. However, it does provide an appropriate tool to create hybrid, versatile, and functional tissue constructs; thus, coupling biofabrication with stimuli-responsive materials, novel maturation processes, and validation procedures will bring us one step closer to successful regenerative medicine. The authors envision that new stimuli-responsive biomaterials that can adapt in a controlled manner to a desired stimulus will be a promising development in the near future.