INTRODUCTION

The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt (TIPSS) originated from imaging studies in the 1960s and 1970s, which led to the establishment of transjugular intrahepatic portal vein cannulation and the creation of a portosystemic shunt.1,2 The first successful clinical application of TIPSS using expandable stents was in 1988 for variceal bleeding.3 The main reasons for its implementation were salvage therapy and for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Despite the introduction of covered TIPSS, studies have not consistently demonstrated a survival benefit in secondary prevention.4 However, controlled trials in the 21st century have led to a paradigm shift in the utility of TIPSS in acute variceal bleeding as a result of careful patient selection and timing of the procedure.

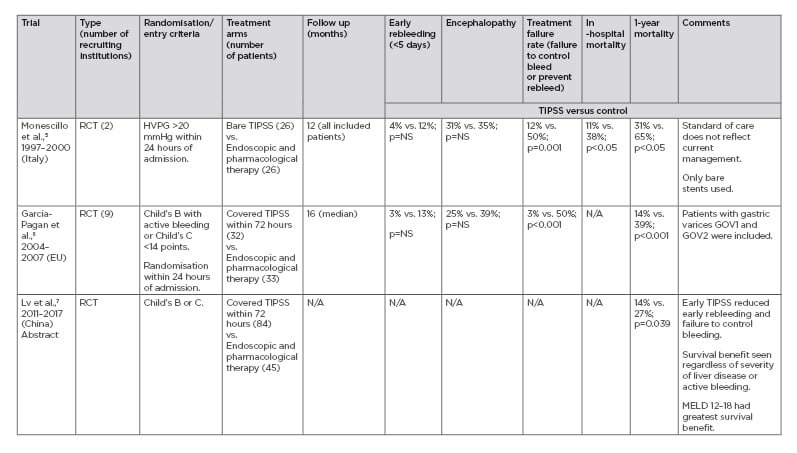

PRE-EMPTIVE TIPSS FOR ACUTE VARICEAL BLEEDING (TABLE 1)

It is important to highlight that pre-emptive refers to TIPSS performed during the acute variceal bleeding episode in a stable patient, in contrast to secondary prevention where patients undergo TIPSS after the acute bleeding episode as an elective procedure. The aim is to select patients at high risk of rebleeding for a TIPSS procedure and at the earliest opportunity. The first of these trials was undertaken by Monescillo et al.5 Patients were randomised to TIPSS or endoscopic therapy if they exhibited a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) >20 mmHg within 24 hours of acute variceal bleeding. The trial demonstrated better outcomes with improved survival in the pre-emptive TIPSS arm compared with standard of care.5 Indeed, patients randomised to TIPSS fared better than those with initial HVPG ≤20 mmHg treated with endoscopic therapy. However, only bare stents were used, and the standard of care did not reflect current practice. Furthermore, the facility to perform HVPG measurement is only available in a few centres and does not reflect the standard of care in many countries. Therefore, this trial had minimal impact on clinical practice.

This study was followed by a randomised controlled trial (RCT) published nearly 10 years ago by Garcia-Pagan et al.,6 who reported 12-month survival of 86% in the pre-emptive covered TIPSS group versus 61% with standard of care in Child–Pugh Class C (Child’s C) cirrhosis patients or Child’s B cirrhosis patients actively bleeding at the time of endoscopy. The standard of care was banding in combination with drug therapy. It is worth noting the high mortality rate of 33% at 6 weeks in the standard of care arm, which is higher than would normally be expected.8 The definition of pre-emptive or ‘early’ TIPSS was within 72 hours of endoscopically controlling the bleed. This was followed by a retrospective post-RCT surveillance study by the same group screening 659 patients, of whom 584 were excluded.9 Again, they found an 86% 12-month survival compared with 70% with endoscopy and drug therapy. However, this was only a trend to improvement compared with endoscopy and drug therapy, as opposed to reaching statistical significance (p=0.056).9

These two RCT were followed by a number of retrospective and prospective audits with variable results.10-14 A French study reported better outcomes with pre-emptive TIPSS, but only 6.7% of those eligible for pre-emptive TIPSS underwent this procedure and this group tended to have less severe liver disease. Furthermore, it was liver disease severity that correlated with survival rather than pre-emptive TIPSS.12 Recent data have led to some debate regarding the inclusion criteria for pre-emptive TIPSS.12-16 While Child’s C disease has been shown to consistently to correlate with improved survival following pre-emptive TIPSS, this has not been the case for Child’s B patients with active bleeding.12-16 A recent large observational study from China showed that only patients with Child’s B disease and active bleeding obtain benefit from pre-emptive TIPSS regarding 1-year survival. However, the findings must be interpreted with caution in light of the intra-observer variability and heterogeneity of reporting active bleeding.16 Moreover, patients with Child’s A disease were also included. Thus, the evidence supporting bleeding as a high-risk criteria is not consistent and further controlled studies are necessary to confirm the utility of this criteria in selecting patients for pre-emptive TIPSS. A recent observational study also showed that patients with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score ≥19 are likely to benefit from pre-emptive TIPSS,15 a finding confirmed by Lv et al.16 It is not clear from these studies if there is a ceiling of severity for liver disease beyond which there is no benefit from pre-emptive TIPSS, although a UK study reported that salvage TIPSS in patients with a Child-Pugh score >13 is likely to be ineffective.17

Table 1: Pre-emptive transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt: Randomised controlled trials.

UPDATES FROM THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2019 (TABLE 1)

As mentioned previously, there are just two published RCT of pre-emptive TIPSS for acute variceal bleeding.5,6 However, a relatively large RCT from China was presented at the 2019 International Liver Congress (ILC), Vienna, Austria, and published in abstract form.7 The key difference between this trial and that of the previous trial of covered stents6 is the inclusion of patients with Child’s B and C cirrhosis without any requirement for active bleeding. Furthermore, active bleeding did not influence the risk of death or transplantation. The results confirmed that pre-emptive TIPSS resulted in improved transplant-free survival in all patient subgroups, with benefit seen particularly for those with a MELD score of 12–18.

A systematic review of individual data of 169 high risk patients undergoing pre-emptive TIPSS studied the benefit of pre-emptive TIPSS when risk was stratified according to age, Child-Pugh Class score, creatinine, and alcohol aetiology.18 All groups obtained a survival benefit, in particular those stratified according to lower risk score.

CONCLUSION

The survival benefit of pre-emptive TIPSS is clear in high-risk patients. However, the high-risk criteria, in particular active bleeding in Child’s B patients, is debatable due to conflicting data from RCT and observational studies.

One of the major barriers to implementation of pre-emptive TIPSS is the logistical issue of arranging a procedure as an ‘emergency’ in a stable patient where there is control of bleeding, even in centres with keen multidisciplinary teams. Clinicians may also be reluctant to accept the benefits of pre-emptive TIPSS, as shown in the study by Thabut et al.12

In conclusion, the data to support universal adoption of early or pre-emptive TIPSS in all high-risk groups are emerging at this time. The results of a UK RCT of pre-emptive TIPSS for variceal bleeding are eagerly awaited in view of the paucity of data from controlled trials.19 A multicentre controlled trial collecting large numbers of patients is a research priority.