Abstract

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare cholestatic disorder of the liver, with strictures in the bile ducts leading to cirrhosis of the liver in a proportion of patients. PSC is commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease and increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma, gall bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Medical therapies are primarily aimed at symptom management and disease-modifying therapies are limited. Endoscopic therapies are used in patients with dominant strictures and liver transplantation is a last resort. In this article, the authors aim to comprehensively review the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of PSC with emphasis on risk of malignancies and management of PSC. The authors also survey the advances in pathogenesis understanding and novel medical therapies for PSC.

INTRODUCTION

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare cholestatic disorder of the liver associated with inflammation and injury with fibrosis in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. A large proportion of patients have associated inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with PSC.1-3 PSC presents with features of cholestatic liver disease; however, patients can present with decompensated liver disease over the long term. PSC is associated with a predisposition to malignancies, including cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), gall bladder cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and colorectal cancer (CRC).4 Diagnosis is largely based on imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP); however, liver biopsy may be needed in a small number of cases. Medical therapies are limited to management of cholestasis in patients with PSC, while endoscopic therapy remains the mainstay when dominant strictures are present.5 Liver transplantation remains the last resort in decompensated liver disease, although recurrence post transplantation is frequent.6 Despite the advances in imaging and diagnostics, therapy options for PSC are still limited, with most patients diagnosed with end-stage disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY, GENETICS, AND PATHOGENESIS

PSC is a rare disease with an incidence rate in northern Europe and the USA of 0.4–2.0 per 100,000 people per year.5 An increasing incidence of PSC has been reported, mainly attributed to the use of MRCP leading to an increase in early diagnosis.7 The median age of presentation is 30–40 years, with a male to female ratio of 2:1.8 In patients of northern European descent with PSC, 62–83% have associated IBD while 20–50% patients from southern Europe and Asia have associated IBD.9 The ratio of ulcerative colitis (UC) to Crohn’s disease (CD) is 6:1 in patients with PSC. A distinct phenotype termed as PSC–IBD has recently been described in association with PSC with features of both UC and CD.10

PSC is a complex multifactorial disease with known genetic associations, both HLA (HLA B8 and HLA DR3) and non-HLA associated. There is known familial association, with the risk being 0.7% amongst first-degree relatives and approximately 1.5% amongst siblings, both 100-times higher than that in the general population.11 Non-HLA associations are found with killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR), major histocompatibility complex (MICA and MICB), intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5), G protein coupled bile acid receptor 1 (GPBAR1) TGR5, multidrug resistance gene-1 (MDR-1), steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR), and its analogue pregnane X receptor (PXR) polymorphisms.12 Despite the common association of PSC with IBD, the HLA association of the two disorders is not characteristic, as demonstrated in a Scandinavian cohort.13 Although PSC is rare, the HLA subtypes associated with risk are rather common and hence the probability of false genetic association remains a problem in study design. This problem is not related to statistical power alone but to the possibility of allelic complexity at a susceptibility locus.14

The leaky gut hypothesis was initially used to describe the pathogenesis of PSC. Due to mucosal injury, increased bacterial translocation into the portal venous system leads to an inflammatory response in the bile ducts, leading to cholangitis and subsequent wound healing by periductal fibrosis. However, a Scandinavian study on this hypothesis showed no significant difference in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or intestinal permeability between PSC patients and controls.15 The gut lymphocyte homing hypothesis was proposed because PSC usually runs a course independent of IBD. Memory T lymphocytes primed in the inflamed gut may trigger and continue inflammation in the periportal region.16 Both these hypotheses are proposed for patients with IBD and PSC. These hypotheses, however, failed to describe PSC patients without IBD and those who develop PSC prior to the development of IBD. The autoimmune hypothesis was proposed due to the presence of autoantibodies like perinuclear antineutrophil antibodies (pANCA) in association with 80% of PSC patients and known overlap syndrome between autoimmune hepatitis and PSC. This hypothesis is based on molecular mimicry of biliary antigens on cholangiocytes and immune response to the same.17 In 2010, the biliary umbrella hypothesis was proposed. There is a loss of the biliary bicarbonate umbrella in patients with PSC, which may increase permeation of protonated bile acids, leading to the injury of cholangiocytes.18 It is also referred to as the toxic bile hypothesis.

The pathogenesis for PSC remains complex, with need for further studies. In addition, various ongoing animal studies may help further elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets for both early and advanced PSC.12

CLINICAL FEATURES, DIAGNOSIS, AND DIFFERENTIALS

Fifteen to forty percent of patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Fatigue and pruritus are the most common symptoms of disease. Ascending cholangitis due to transient biliary obstruction may be a presenting manifestation in patients with fever, chills, and right upper quadrant pain. Patients may present with recurrent episodes of jaundice. In patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, decompensation is evident in the form of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or bleeding.19 Laboratory anomalies include increased bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. Transaminases <300 U/L are seen in patients with PSC. Albumin is normal in early stages and decreases with progression of liver disease. Hypergammaglobulinaemia and elevated IgG levels are seen in patients with PSC. Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) is rarely positive in patients with PSC.20 Autoantibody testing is not a contributing factor in the diagnosis of PSC. Although pANCA is commonly seen in patients with PSC, it is not specific. Antinuclear and smooth muscle antibodies are seen in patients with PSC in low titres. In patients with autoimmune hepatitis–primary sclerosing cholangitis (AIH–PSC) overlap, the antibodies are seen in higher titres.21 Although AMA is rarely positive in patients with PSC, overlap between primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and PSC is rarely reported.22

Cholangiography is the gold standard for diagnosis of PSC. MRCP is the investigation of choice for diagnosis. MRCP avoids radiation and contrast media associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP). However, MRCP provides suboptimal visualisation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. Multifocal short segmental strictures are seen on MRCP suggesting a ‘beads on string appearance’.

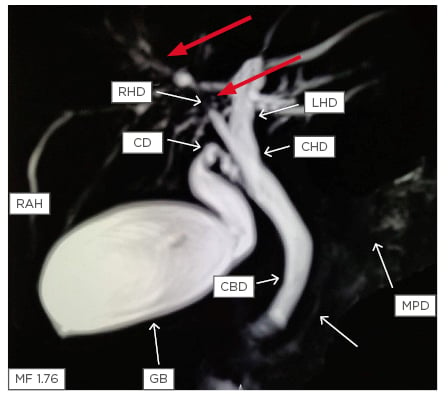

Both intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts are involved in most of the patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing stricture in the right hepatic duct (red arrows) with beading in the smaller ducts in the right lobe of the liver (white arrows).

CBD: common bile duct; CD: cystic duct; CHD: common hepatic duct; GB: gall bladder; LHD: left hepatic duct; MPD: main pancreatic duct; RAH: right anterior hepatic duct; RHD: right hepatic duct.

Isolated intrahepatic ductal involvement is seen in approximately 25% of patients. Isolated extrahepatic involvement is rare (<5%). Also gall bladder, cystic duct, and pancreatic ducts may show involvement in PSC.23 MRI can also help in prognostication in patients by assessment of relative enhancement using hepatocyte-specific contrast (gadoxetate disodium) with a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 92% and correlates with clinical outcomes.24

Histologic features in PSC include damage and loss of medium and large-sized bile ducts both within and outside the liver. This picture is not classically evident on liver biopsy and ductopenia may be seen in the small sized bile ducts due to obstruction. Onion skin fibrosis of the bile ducts is a classical feature, but is evident in only 15% patients following liver biopsy.25 Staging systems for PSC have been described on liver biopsy, which include Stage 1) cholangitis with portal hepatitis, Stage 2) periportal fibrosis, Stage 3) septal fibrosis or bridging necrosis, and Stage 4) biliary cirrhosis.26 Liver biopsy is performed to rule out other diseases, to look for AIH overlap, or in cases of suspected small duct PSC.

VARIANTS OF PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Overlap Syndrome

Suspicion of overlap with AIH should be high in situations with raised transaminases (>5-times the upper limit of normal) with raised serum Ig levels (IgG >2-times the upper limit of normal) with features of PSC on imaging and evidence of cholestasis (raised alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase) on biochemistry. Biopsy is required for confirming the diagnosis. Overlap of PSC with AIH is known to occur in 7–14% of patients with AIH. Treatment with immunosuppressants is useful, although their impact on fibrogenesis and cirrhosis is not as pronounced as with AIH without PSC.27 PSC is also known to have overlap with PBC in few case reports.22 A genetic risk locus has been described for coexistence of PSC with PBC (chromosome 1p36).28

Small Duct Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Involvement of small ducts only can be seen in 5–15% of patients. Liver biopsy is required for diagnosis of small duct PSC. Small duct PSC progresses to large duct PSC in 25% of patients. Small duct PSC in the absence of large duct involvement is not associated with predisposition to CCA. The diagnosis of small duct PSC is difficult to make, especially in settings without concomitant IBD. Small duct PSC is also more commonly associated with Crohn’s disease.29 Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis Type 3 is often similar in clinical presentation and histopathology to small duct PSC.30

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

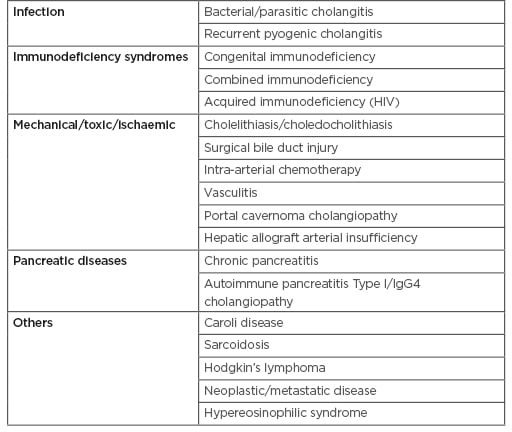

Causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis need exclusion prior to diagnosis of PSC (Table 1).31

Table 1: Causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis that mimics primary sclerosing cholangitis.30

Dominant Strictures and Risk of Malignancy

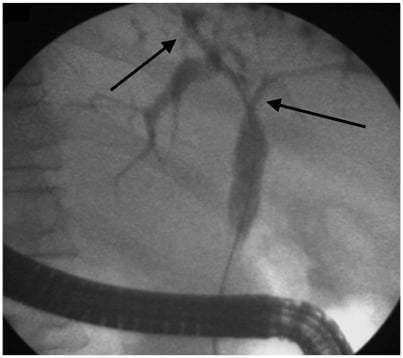

Various classifications have been used to describe the cholangiographic findings in PSC. The one commonly used and correlating with prognosis is the Amsterdam Classification given by Ponsioen et al.32 These criteria are not specific for PSC and must be interpreted in the context of patient demographic data and clinical features. Dominant strictures have been defined in patients with PSC as stenosis of <1.5 mm in the common bile duct and <1.0 mm in the hepatic duct within 2 cm from the main hepatic confluence. This definition primarily applies to stenosis seen on ERCP (Figure 2). MRCP is not used to define dominant strictures considering the insufficient spatial resolution and lack of hydrostatic pressure.33 Multiple dominant strictures may be seen in up to 12% of patients. Due to the risk of malignancy, in settings with worsening clinical symptoms (such as jaundice and cholestasis), rising liver function tests, or the development of a new stricture as identified by MRC, it is best to consider stricture dilatation with sampling via brush cytology to rule out malignancy. Risk of malignancy in one cohort with dominant strictures was 6%.33 In the same cohort, endoscopic intervention in dominant stricture via dilatation resulted in improved transplant-free survival at 5 years (81%) and 10 years (52%).

Figure 2: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography showing presence of dominant stricture at hilum extending into the right and left hepatic duct (arrow) with beaded appearance of intrahepatic ducts (arrow).

PSC is a risk factor for the development of CCA, gall bladder cancer, HCC, and colon cancer. The estimated lifetime risk of CCA is 8–36% in patients with PSC. About 50% of patients have CCA diagnosed during the first presentation or during the first year following diagnosis of PSC. MRI can be used for diagnosis of CCA in PSC. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels are useful for diagnosing CCA; however, these may be elevated in patients with cholangitis with obstructive jaundice in PSC. A cutoff of 20 IU/mL may be used for diagnosing early CCA in PSC patients; however, the sensitivity is 78% and specificity 67%. Higher cutoffs lead to loss of sensitivity. Biliary brush cytology during ERCP is useful for diagnosis with 100% specificity; however, sensitivity is low at 43%. The addition of fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) to biliary sampling increases sensitivity to 51%. Presence of polysomy on FISH is highly suggestive of CCA.34 Yearly carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels tests and MRI are suggested for the surveillance of CCA in patients with PSC.

Lifetime risk of gallbladder cancer is 3–14% among patients with PSC. Patients with gall bladder polyps >8 mm in size are more likely to harbour malignancy and hence warrant cholecystectomy. Cirrhosis in patients with PSC predisposes them to the development of HCC. Lifetime risk of HCC is approximately 0.3–2.8%, hence HCC surveillance in cirrhotic patients with PSC is warranted.35 Pancreatic cancer risk in PSC patients has been reported to be 14-times higher than in the general population as per a study from Sweden in 2002.36 Another study from the USA reported >10-times increased risk of pancreatic cancer in patients of PSC with IBD.37 There is still debate on the diagnostic overlap between CCA and pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic ductal changes are known in PSC; however, the exact mechanism of carcinogenesis is not known.

CRC risk is 4-times higher in patients with PSC and IBD than those with IBD alone. The subset of PSC patients without IBD does not have increased CRC risk.38 Patients who develop CRC with a background of PSC–IBD have a younger age of symptom onset with a predilection for right-sided colonic malignancies. Risk factors in the presence of IBD include duration of disease, extent of disease, and presence of PSC. In view of the quiescent nature of IBD in patients with PSC, colonic mapping biopsies are warranted in patients with PSC for diagnosis of IBD. In the presence of PSC, patients with IBD should undergo yearly colonoscopies for CRC screening.39

RISK STRATIFICATION

As with cirrhotic patients, the Child–Pugh score and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) are used for risk stratification. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is an independent predictor of outcomes in patients with PSC. ALP can be considered a continuous variable or single measurement for prognostication. The most commonly used risk score is the revised Mayo Score, which includes age, albumin, bilirubin, variceal bleeding, and AST levels. The score has good prediction of survival; however, it also has poor utility in early disease.5 The use of the revised Mayo Score obviates the need for biopsy in risk stratification. Another score called the Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis Risk Estimation Tool (PREsTo), consisting of nine variables (bilirubin, albumin, ALP, SGOT, platelets, haemoglobin, sodium, patient’s age, and years since diagnosis of PSC), is better than other available risk stratification tools (MELD and revised Mayo Score) for prediction of decompensation in patients with PSC.40

MANAGEMENT OF PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

Medical Management

No single drug or treatment has been proven to prolong transplant-free survival in PSC. The hydrophilic bile acid, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), has been extensively studied. However, evidence showing the long-term benefit of UDCA is unclear and its use remains controversial. A study of 105 patients using low-dose of UDCA (13–15 mg/kg/day) showed biochemical improvement but lacked evidence of clinical improvement.41 A landmark, large, multicentre study42 using a high dose of UDCA of 28–30 mg/kg/day showed that the patients receiving the drug fared worse when compared to placebo, with substantially more adverse, clinically important outcomes, such as the need for transplantation and the development of varices. At this point, no indication exists for using the higher doses of 28–30 mg/kg/day of UDCA. Nonetheless, UDCA remains widely used, typically at moderate doses of 15–20 mg/kg/day. The chemoprotective effect of UDCA is not verified, with small retrospective studies showing benefit in chemoprevention of CRC in patients with PSC. On the other hand, few studies have shown increased risk of CRC in PSC patients who receive high doses of UDCA.43

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines recommend UDCA for use in high-risk settings for CRC prevention in patients with long duration and extensive disease with IBD. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines on the other hand do not endorse use of UDCA for prevention of CRC.34,44,45

Immunosuppressive and Other Agents

Other treatments that have been tested without any proven clinical benefit or improvement of liver biochemistries include:

- Azathioprine46

- Budesonide47

- Docosahexaenoic acid48

- Metronidazole49

- Minocycline50

- Mycophenolate mofetil51

- Nicotine52

- Pentoxifylline53

- Pirfenodone54

- Prednisolone55

- Tacrolimus56

- Vancomycin57

- Methotrexate58,59

- Novel Therapies

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists (e.g., obeticholic acid, 6α-ethyl chenodeoxycholic acid) and 24-norursodeoxycholic acid, a side-chain-modified UDCA derivate resistant to amidation which undergoes cholehepatic shunting, may be novel treatment options. A Phase II study in patients with PSC demonstrated the plausible effectiveness of the 24-norursodeoxycholic acid derivative with significant improvement in AP and bilirubin levels. The side effects were unremarkable with no change in IBD activity.60 Large Phase III studies are ongoing into the use of 24-norursodeoxycholic acid in PSC. Obeticholic acid is currently being evaluated in a Phase II study in PSC.61 Obeticholic acid reduces toxic bile production and induce secretion through FXR mediated pathways. Obeticholic acid also reduces FGF19 levels to decrease fibrogenesis.62 Fibrates, with their global pleiotropic and anti-inflammatory properties, may be an alternative novel treatment strategy with reduction in production of toxic bile and stimulation of canalicular secretion. Two pilot studies have evaluated the role of fibrates in PSC. Twenty-one patients treated over 6–12 months showed benefit in biochemical markers; however, there is a need for larger placebo-controlled studies.63 Various antibiotics have been tried in PSC in an attempt to change the microbiological milieu in the intestine; however, there have been concerns regarding emerging resistant organisms and hence their chronic use is not encouraged. Apical sodium bile acid transporter inhibitors like maralixibat have been studied in a Phase II trial in PSC, showing improvement in bile acid levels but no significant improvement in ALP and bilirubin levels.64 Faecal microbiota transplantation remains a feasible option for patients in theory, but no studies are currently available to attest to its benefit in this setting.

ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT

Patients with dominant strictures, even if CCA is excluded, have a substantially worse prognosis than those without. Endoscopic intervention for dominant biliary strictures in patients with symptomatic disease appears beneficial.33 Guidelines recommend balloon dilatation as first-line endoscopic treatment.65 Several studies have shown that short-term stenting is not superior to balloon dilatation alone.66,67 Routine stenting after dilation of a dominant stricture is not required, whereas short-term stenting (1–2 weeks) may be required in patients with severe stricture. Long-term stent placement is associated with an increased risk of complications and a need for unscheduled stent exchanges. The role of metal stents, which are fully covered, removable, and self-expandable, in PSC is yet to be established. Patients undergoing ERCP should have antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent post-ERCP cholangitis. Patients with PSC are also at higher risk of pancreatitis and the routine use of diclofenac suppositories is warranted in these patients prior to or immediately after ERCP.65

Screening for varices should be performed if evidence suggests cirrhosis or suspicion of portal hypertension. Patients with PSC can develop varices even before cirrhosis develops. A total colonoscopy with mapping mucosal biopsies is advised to exclude IBD once PSC is diagnosed. For patients with confirmed colitis, annual colonoscopic surveillance for colorectal dysplasia or neoplasia is recommended. Percutaneous biliary drainage for treatment of dominant strictures can be performed in PSC patients with altered anatomy that prevents successful ERCP, such as Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy or gastric bypass, or as a rescue therapy after failed endoscopic access. It should not be attempted as first-line therapy because of the risk of complications, including hepatic arterial injury, haemobilia, and cholangitis.68-70

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Biliary reconstruction by biliary-enteric drainage allows prolonged clinical improvement, with the resolution of jaundice and cholangitis, but is associated with increased risk of cholangitis and mortality. Postoperative scarring also increases the difficulty of liver transplantation. Surgical drainage procedures have largely been discontinued in favour of transplantation due to the superior outcomes of liver transplantation.71

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Liver transplantation remains the only curative treatment for PSC, albeit with a substantial risk of disease recurrence. PSC is a well-established indication for liver transplantation in patients with decompensated liver disease (MELD >14), intractable pruritus, or recurrent bacterial cholangitis.72 PSC accounts for <5% of transplant indications in the USA and 15% of transplants in Scandinavia. Outcomes of liver transplant in PSC patients are better than with other indications considering the young age at which the patients are transplanted: 5-year survival rates are approximately 85%.73 PSC patients have predilection for peritransplant hypercoagulability, although no specific prophylaxis is required for this. Another important consideration in these patients is the type of biliary anastomosis, with duct-to-duct anastomosis being better than bilioenteric anastomosis in PSC. This preference is largely based on case control studies, which demonstrate a higher rate of cholangitis in patients with bilioenteric anastomosis.74 No specific guidance for immunosuppression post-transplant for PSC is available and triple drug regimens are used. At least 20% of transplanted patients will develop recurrent disease after transplant. Colectomy prior to liver transplant is associated with lower rates of recurrence. No single factor has consistently been associated with increased recurrence risk post-transplant.75

SYMPTOMATIC TREATMENT

The most troublesome symptom is pruritus. Dominant strictures should be sought and actively managed. Medical management of pruritus is directed by the severity of the underlying pruritus. Mild pruritus may be treated with skin emollients and possibly antihistamines. First-line therapy for severe pruritus is with the bile acid sequestrant cholestyramine. Second-line therapies include rifampicin, naltrexone, sertraline, and phenobarbitone. At present, no specific therapies for fatigue exist. Patients with PSC have an increased risk of osteoporosis and might also be deficient in vitamin D and other fat-soluble vitamins. Patients are advised to undergo weight-bearing exercise and take calcium and vitamin D supplementation.44

CONCLUSION

PSC is a chronic cholestatic liver disease, often associated with cirrhosis with increased risk of malignancy. There is a need for surveillance strategies for detection of various cancers. Medical therapies are sparse, with endoscopic therapies available for dominant strictures. Liver transplantation remains an option in decompensated liver disease, intractable pruritus, and rarely in settings with CCA. Although the clinicians continue to treat PSC, ongoing research in many areas, including effective medical therapies, diagnostic tools, genetics, pathogenesis, and biliary and bowel complications after liver transplantation may open doors to better management of this enigmatic disease.