Meeting Summary

Treatment decisions in chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) are complex and require the evaluation of many factors at each stage of therapy. Many patients will become resistant or intolerant to the first and subsequent lines of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) they receive, requiring them to switch to a different TKI. Clinicians are faced with many considerations when choosing subsequent treatments and an important issue is how best to manage failure on a second-generation TKI. During an interactive and case-based, Incyte-sponsored, satellite symposium at the 2019 European Hematology Association (EHA) congress, Dr Janssen and Prof Apperley discussed the current best practices for managing patients failing imatinib or second-generation TKI, considering whether second-generation TKI should be used sequentially and the timing of the introduction of a third-generation TKI (ponatinib). Dr Soverini and Dr de Lavallade discussed how regular BCR-ABL response monitoring and mutational analysis are integral to CML patient management. They highlighted the clinical relevance of low-level mutations and the necessity to prevent clonal expansion of these TKI-resistant mutants, and the accumulation of additional mutations, by switching to an effective TKI in a timely manner.

Introduction

The significant advances in the treatment of patients with CML over the last two decades have resulted in an improved prognosis for most patients, contributing to their life expectancy approaching that of the general population.1 Improvements in the prognosis of CML patients was also accompanied by a shift in the management of the disease and the treatment objectives. While in 2001 the treatment objective was to prolong the survival of patients, the main treatment goal today is for patients to achieve a deep molecular response, which gives them the best chance to successfully stop treatment. The introduction of imatinib revolutionised the treatment landscape of CML, and with this agent the majority of patients will eventually attain a deep molecular response;2,3 however, for a proportion of patients the treatment outcomes with imatinib are unsatisfactory. Imatinib and second-generation TKI can become inactive once point mutations in the BCR-ABLTKI binding domain appear.4 When this occurs, there is a need for an alternative TKI that is active in the presence of such resistant mutations. During an interactive and case-based satellite symposium, hosted by Incyte during the 2019 EHA meeting, Dr Janssen and Prof Apperley discussed the current best practices in CML patients failing on imatinib or a second-generation TKI, after which Dr Soverini and Dr de Lavallade discussed the technical aspects related to mutation testing in CML.

Dealing with Imatinib or Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Failure in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia

Doctor Jeroen Janssen

Over the last decade, regular BCR-ABL response monitoring has become an important part of managing CML patients who are treated with a TKI. This approach allows physicians to quickly identify patients with a suboptimal response (‘warning’ or ‘failure’), as defined by the European Leukemia Network (ELN) criteria, and switch them to an alternative TKI. In the case of a ‘warning’, the outcome might improve, but close follow-up is warranted. In the case of ‘failure’, immediate action is required (i.e., a TKI switch).5 In the case of a ‘warning’ or ‘failure’, the ELN and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on CML recommend a mutational analysis of the BCR-ABLkinase domain.5-7 If a mutation is discovered, it is important to choose the appropriate next TKI, e.g., by using the traffic-light coded heat map that lists the sensitivity of most common mutations for all currently

available TKI.8

What can we Expect from Switching Between Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors?

Professor Jane Apperley

There is a lack of clinical data on the effect of switching from one second-generation TKI to another (i.e., switching between nilotinib, dasatinib, or bosutinib) after initial failure on imatinib. The scarce data available indicate that the rate of complete cytogenetic responses to a second-generation TKI in the third-line setting was low (ranging from 11% to 32%).9-11 Furthermore, the durability of these responses was limited;10-12 for example, in a Phase I/II study 71% of the patients who received bosutinib after imatinib and dasatinib/nilotinib failure discontinued therapy within 2 years.12 Notably, almost half of the patients in these trials switched between second-generation TKI for reasons of intolerance, and the proportion of truly resistant patients was low. As such, these studies do not provide firm support for a switch between second-generation TKI in TKI-resistant patients.9-12

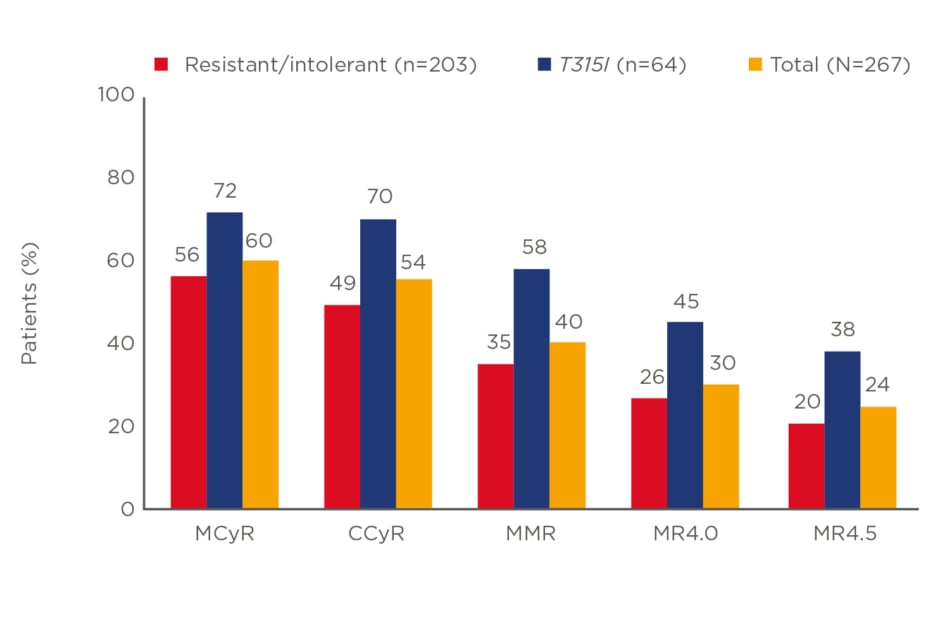

When switching from a second to a third-generation TKI (i.e., ponatinib), deep and durable responses can be achieved. In the PACE trial, chronic-phase CML patients treated with ponatinib after resistance or intolerance to dasatinib or nilotinib resulted in a 49% complete cytogenetic response and a 35% major molecular response. An MR4.5 was achieved by 20% of patients (Figure 1).13

Figure 1: Rates of responses to ponatinib in the PACE trial in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia.

CCyR: complete cytogenetic response; MCyR: minor cytogenetic response; MMR: major molecular response; MR4.0/4.5: deep molecular response 4.0/4.5.

Adapted from Cortes et al.13

Importantly, the response to ponatinib proved to be durable with 59% of the responders remaining in major molecular response after 5 years. The latter translated into an estimated overall survival of 73% at 5 years.13 For patients treated with ponatinib, close monitoring and the use of preventive measures are warranted to decrease the risk of toxicity.14 Finally, for the small proportion of patients who are not responding to multiple lines of therapy, including ponatinib, a donor search for an allogeneic stem cell transplantation can

be started.14

Optimising Mutation Testing in Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia

Doctor Simona Soverini and Doctor Hugues de Lavallade

As indicated before, patients with a suboptimal response or a TKI treatment failure should undergo mutational analysis, as recommended by the ELN and NCCN guidelines.5-7 Sanger sequencing has long been the gold standard to perform this mutational analysis, but evidence has accumulated showing that next-generation sequencing (NGS) is markedly more sensitive. NGS can detect mutations with a sensitivity of approximately 3%, while Sanger sequencing has a sensitivity of 15–20%.15,16 As such, NGS allows the detection of TKI-resistant mutations much earlier and at lower frequency levels. Data generated by Dr Soverini indicate that the detection of low-level mutations is of clinical relevance given the fact that all these low-level mutations expand if there is no switch to an appropriate TKI.17,18 In addition, recent data reported by Schmitt et al.19 indicate that advanced CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia patients with BCR-ABL mutations have a greater likelihood of acquiring additional mutations. With this in mind, Dr Soverini and Dr de Lavallade concluded that it is essential to prevent the clonal expansion of these TKI-resistant mutants and the accumulation of additional mutations by switching to an appropriate TKI in a timely manner.