PREDICTING probability of metastasis in prostate cancer may be more reliable, thanks to a new gene signature identified by researchers from the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York City, New York, USA.

The newly identified gene signature can help to determine the likelihood of progression from localised disease to metastatic spread, and the likely response to anti-androgen therapies. The researchers believe it may also be helpful in predicting response to other treatments, and even development of new therapies to address or prevent advanced prostate cancer.

Most prostate cancers remain confined to the prostate, with a >99% 5-year survival rate; however, metastatic prostate cancer is frequently considered incurable, with a 30% 5-year survival rate. Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in males in the USA. Determining which group a patient falls in, from a likelihood of progression perspective, is an important requirement for ensuring at-risk patients are treated early and adequately, and avoiding unnecessary treatment for those cancers that were unlikely to spread.

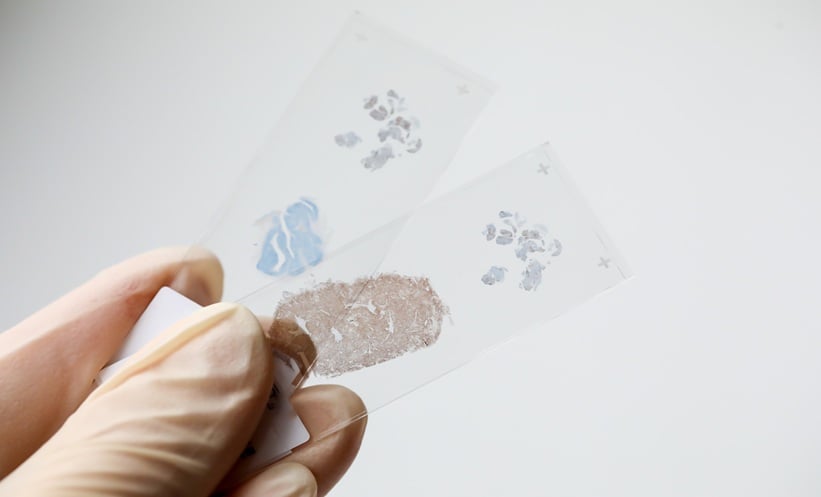

To identify this new gene signature, the researchers used a first-of-its-kind mouse model, reflecting the human form of prostate cancer and revealing that prostate cancers with metastatic spread to bone have a different molecular profile. This difference revealed 16 genes involved in metastatic spread, collectively called META-16. The study went on to test this gene signature against biopsies of known localised prostate cancers; the cancer outcomes were blinded to the researchers. The META-16 signature was highly effective at predicting time to metastatic spread and anti-androgen therapy response.

The clinical significance of the finding was outlined by the study’s senior author, Prof Cory Abate-Shen, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “If we could know in advance which patients will develop metastases, we could start treatments earlier and treat the cancer more aggressively,” explained Prof Abate-Shen. “Conversely, patients whose disease is likely to remain confined to the prostate could be spared from getting unnecessary therapy.”

The research team are refining the test, for both future prognostic use and for development of potential targeted therapies. “The genes in our signature are not only correlated with metastasis, they appear to be driving metastasis,” said lead author Dr Juan M. Arriaga, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “That means that if that we can suppress the activity of those genes, we might be able prevent the cancer from spreading or at least improve outcomes.”