Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a complex autoimmune rheumatic disease that is characterised by widespread skin and internal organ fibrosis, immune system dysregulation, and vasculopathy. The disease carries a significant burden of pain and disability that is potentially life-limiting because of major internal organ-based complications. Early diagnosis is vital and key investigations include the detection of SSc-associated autoantibodies and nailfold capillaroscopic abnormalities. Patients should be managed by a dedicated, specialist, multidisciplinary team. There is now a range of effective treatments available for many of the complications associated with the disease. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation may benefit a small subset of patients with very poor prognosis SSc. Important advances have been made in understanding the aetiopathogenesis of SSc, which is driving clinical trials of new therapeutic approaches. The purpose of this review is to provide a clinically focussed description of the relevant aetiopathogenesis, clinical expression of disease, approach to the assessment and treatment of SSc, and highlight the recent advances and future challenges associated with this complex disease.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a complex autoimmune rheumatic disease that is characterised by widespread skin (scleroderma) and internal organ fibrosis, immune system dysregulation, and vascular alterations.1-4 SSc is a rare rheumatological condition (prevalence: ~20 per million) and is more common in females than males (~7:1).5 The purpose of this review is to provide a clinically focussed description of the aetiopathogenesis, clinical expression of disease, approach to the assessment and treatment of SSc, and highlight the recent advances and future challenges associated with this complex disease.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of SSc is complex and includes vascular alterations (vasculopathy), immune system dysregulation, and aberrant tissue fibrosis.1-3 It is believed that key interactions between vascular changes and early immunological alterations are central to the generation of the SSc-phenotype.1,2 Vasculopathy is thought to occur early in the course of the disease including defective/reduced/uncontrolled mechanisms of vascular repair.1,2 However, the trigger of this early putative vascular injury remains elusive. Ineffective neoangiogenesis, which can be assessed using nailfold capillaroscopy, is clearly apparent in SSc. A key vascular alteration in SSc is a critical imbalance between factors promoting vasoconstriction (e.g., endothelin) and vasodilation (e.g., nitric oxide).1 Local ischaemia (hypoxia) contributes to promote a profibrotic phenotype. Immune (both innate and adaptive) system activation is seen in SSc.1,2 For example, many patients have evidence of SSc-associated antibodies and there is a rich perivascular infiltrate seen in the skin of patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc. The close relationship between cancer and anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies further highlights the role of immunological abnormalities in SSc.2,6 In these patients, there is a link between cancer-related autoantigen (i.e., mutated RNA polymerase III) recognition and an autoimmune response.7 Type I interferon and interferon-inducible genes have been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of SSc.8,9 Subsequent to vascular injury and immune disturbances, activated fibroblasts result in the excess deposition of extracellular matrix, which includes collagen, resulting in organ dysfunction and tissue fibrosis.1,2 Fibroblast transition to myofibroblasts is believed to be a cardinal step in the ultimate stage of SSc pathogenesis.2 Although genetic abnormalities are the strongest risk factor for the development of SSc, a family history of the disease is rare.10 Susceptibility genes identified so far belong in a very large majority to immune mediators, further highlighting the immune component of the disease. Recent research has highlighted the key role of epigenetic modifications in genetically susceptible individuals; for example, those that link inflammatory and fibrotic pathways.2,11

CLINICAL FEATURES OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

One of the great challenges in the management of patients with SSc is the significant clinical heterogeneity of disease within the SSc-spectrum of disorders. Skin thickening (i.e., scleroderma) can occur as an isolated phenomenon (e.g., morphoea) or as part of a systemic, multiorgan, autoimmune connective tissue disease (e.g., SSc). However, characteristic SSc-like organ involvement can also occur in the absence of skin involvement (‘scleroderma sine scleroderma’), which may represent about 10% of SSc patients.

Skin

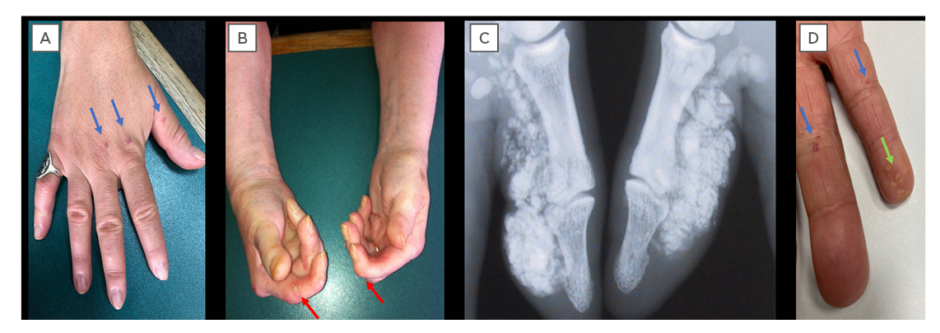

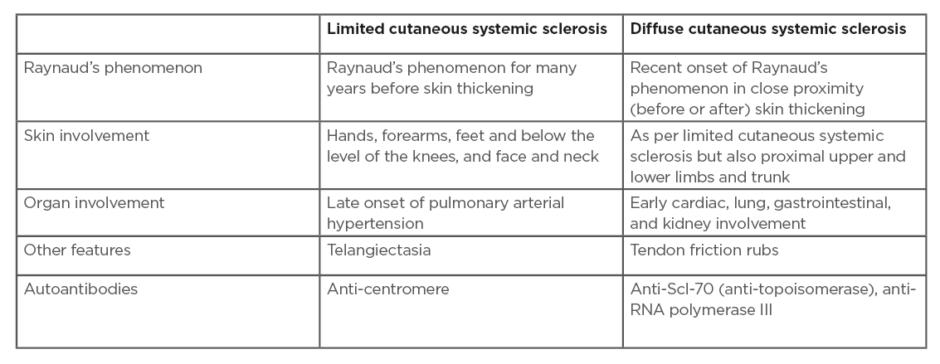

Scleroderma (Figure 1) is a cardinal feature of SSc-spectrum disorders. The distribution of skin disease allows classification of patients into two major subsets: limited and diffuse cutaneous SSc (Table 1).12 Skin involvement in limited compared to diffuse disease does not extend proximal to the elbows/knees, or involve the chest/abdominal wall. Sclerodactyly refers to scleroderma of the digits. The sine scleroderma subset may resemble the limited cutaneous type, in that internal organ manifestations are the major determinant of outcome. Disease subtype has important prognostic implications including internal organ involvement (Table 1). In early SSc disease the fingers often have a puffy appearance.13 Later in the course of the disease, the skin may atrophy; however, patients can be left with permanent joint contractures. Calcinosis (subcutaneous and intradermal calcium deposition) commonly affects 20–40% of patients with SSc, and is often subclinical (Figure 1).14

Figure 1: Cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis.

A) Sclerodactyly and telangiectasia (blue arrows); B) digital pitting scars (red arrows) and hand contractures; C) radiographic calcinosis; and D) visible calcinosis (green arrows) and telangiectasia (blue arrows).

Table 1: Disease subsets in systemic sclerosis.

Adapted from LeRoy et al.9

However, calcinosis can cause significant pain from ulceration through the skin, superadded infection, and local pressure effects.15 Telangiectasia (superficial dilated cutaneous) blood vessels can be associated with significant anxiety and distress from body image dissatisfaction (Figure 1).

Digital vasculopathy

Almost all patients with SSc experience events of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Raynaud’s typically affects the fingers and toes and is provoked by cold temperatures and or emotions/stress. Stereotypical colour changes (pathophysiological mechanisms in parentheses) are initial pallor (vasospasm), followed by cyanosis (sequestration of deoxygenated blood), and finally, hyperaemia (reperfusion).16 However, not all colour changes are reported by individuals during Raynaud’s phenomenon.16 Patients may also experience other symptoms such as numbness and tingling. Unlike patients with primary (idiopathic) Raynaud’s phenomenon, patients with SSc can develop persistent ischaemic tissue loss.17 Digital (finger and toe) ulcers are common in patients with SSc, with half of patients reporting a history of ulceration.18,19 Digital ulcers often occur early in the course of the disease; 75% will experience within the first 5 years after their diagnosis, and are associated with a more severe disease course, including internal organ involvement.18,20 Ulcers are often exceptionally painful and significantly impact upon hand function and quality of life, including affecting the patient’s ability to carry out their chosen occupation.21,22 Digital ulcers may be infected, in particular by Staphylococcus aureus, and can potentially progress to osteomyelitis.23 Patients with SSc can also develop critical digital ischaemia (gangrene), which is a medical emergency and requires prompt assessment.24 The peripheral pulses should be assessed early in patients with critical digital vascular disease as proximal large vessel disease could potentially be amenable to therapeutic intervention.24

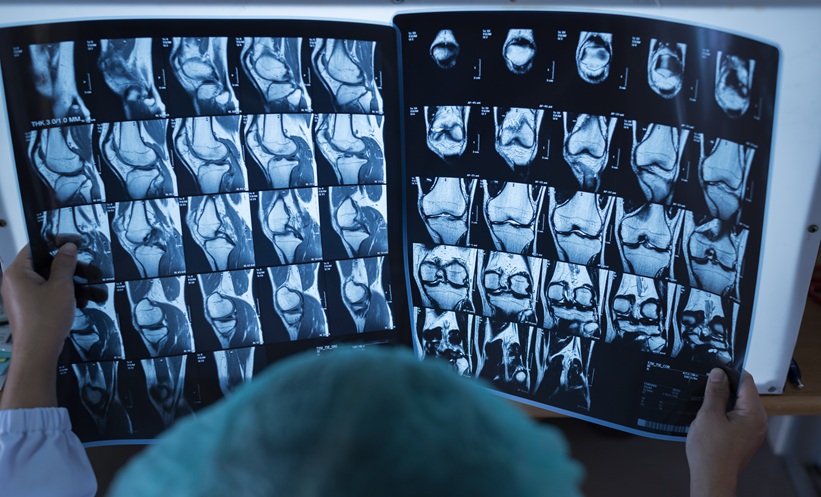

Cardiorespiratory

Involvement of the entire cardiovascular system can occur in patients with SSc including, but not limited to, inflammatory/ischaemic/fibrotic cardiac disease and abnormalities of the conduction system.25 An increased risk of macrovascular disease has also been reported in patients with SSc26 but it may not always relate to classical atherosclerosis and SSc vessel remodelling, which primarily affects small vessels but sometimes also targets larger ones. Respiratory complications such as interstitial lung disease (Figure 2) and pulmonary hypertension are now the leading causes of death in SSc.27 Evidence of Interstitial lung disease is present in half of patients when high-resolution CT (HRCT) is systematically performed and approximately one third develop progressive interstitial lung disease.28-30 Risk factors include, but are not limited to, baseline lung involvement on HRCT, older age, male sex, presence of anti-Scl-70 (anti-topoisomerase) antibodies, and absence of anti-centromere antibodies.29,30

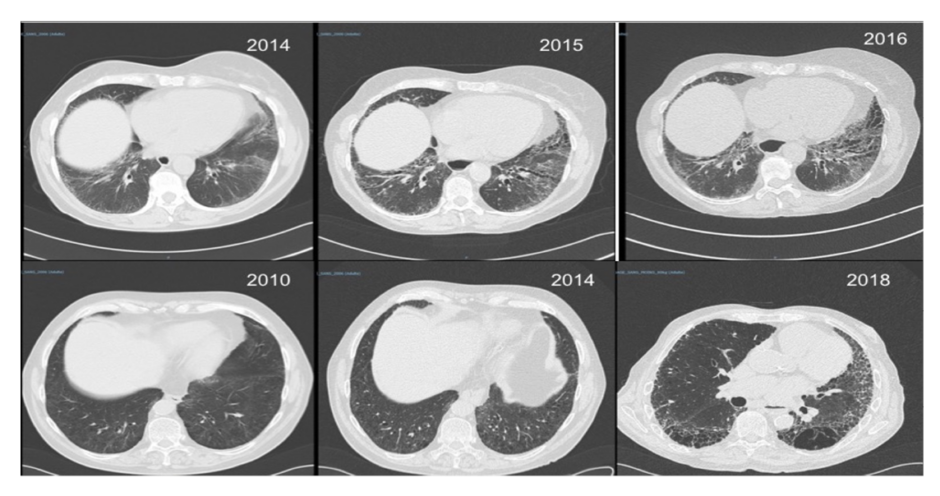

Figure 2: Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis.

Two patients with systemic sclerosis and rapidly (top row) and slowly (bottom row) progressive interstitial lung disease.

Gastrointestinal

The entire length of the gastrointestinal tract can be affected and this is almost universally seen in patients with SSc.31 Reduced oral aperture, impaired upper limb function, and low mood can result in reduced oral intake. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is very common, along with swallowing difficulties and motility issues in the large bowel. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth can result in significant abdominal symptoms including bloating, distension, and diarrhoea. Gastric antral vascular ectasia, otherwise known as ‘watermelon stomach’ because of the striking visual appearance on endoscopy, can result in significant blood loss from the gastrointestinal tract.31 Fecal incontinence is under-recognised, though reported by patients, and can result in significant distress and reduced quality of life. Hepatobiliary involvement can occur, including primary biliary cirrhosis which has been reported to occur in around 2% of patients with SSc.31,32

Renal

The scleroderma renal crisis is a medical emergency. Patients typically present with features of a hypertensive emergency.33 Investigations typically reveal acute kidney injury and possible features of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. Risk factors for scleroderma renal crisis include early disease (<3 years duration), diffuse cutaneous SSc, anti-RNA polymerase III antibody, corticosteroid exposure (usually >15 mg/day), and tendon friction rubs.33 This was previously the leading cause of death in SSc but is now usually a survivable complication because of the introduction of treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Renal outcome is variable; some patients may require life-long renal replacement therapy, but around half of those requiring renal replacement therapy eventually no longer require dialysis. Recovery can occur for several years post renal crisis and ~40% of patients may recover sufficient renal function to no longer require renal replacement therapy.34

Musculoskeletal

Widespread involvement of the musculoskeletal system can occur in patients with SSc. Joint pains and stiffness are common and often multifactorial from skin tightness/sclerosis and finger contractures. Patients can develop both inflammatory (i.e., rheumatoid-like) and non-inflammatory (i.e., degenerative/osteoarthritic) arthritis. Inflammatory muscle disease (myositis) can develop in patients with SSc and typically affects the proximal musculature. Bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome can occur early in the disease course of patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc. This is a high contributor to disability in SSc patients. Acro-osteolysis refers to bony resorption of the terminal digital tufts and is well-recognised in SSc.

Non-fatal morbidity

SSc carries a significant burden of non-lethal morbidity. Fatigue is common, often multifactorial, and difficult to treat, akin to many rheumatological conditions. Pruritus can be marked in patients with early diffuse cutaneous disease. Low mood or depression and sexual dysfunction are not uncommon in patients and should be actively considered by clinicians.35,36

DIAGNOSIS OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

There is no single diagnostic test for SSc. The diagnosis of SSc is usually based on the individual clinical features and from the results of targeted investigations such as SSc-associated autoantibodies and nailfold capillaroscopy. For the general physician, the diagnosis of SSc is very unlikely in the absence of Raynaud’s phenomenon and distal skin involvement (e.g., sclerodactyly). However, there are caveats to this generalisation. The 2013 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) SSc classification criteria are a helpful reference tool for assessing patients with possible SSc.37 Involvement of skin proximal to metacarpophalangeal joints is usually diagnostic of SSc; however, it is important for the clinician to be aware of a number of important scleroderma mimics. Raynaud’s phenomenon can occur soon (up to 1 year) after the onset of skin sclerosis in patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc.12 Furthermore, very early diagnosis of SSc can be established in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon, puffy fingers, and positive antinuclear antibodies, and is confirmed by the presence of SSc-associated autoantibodies and/or capillaroscopic abnormalities.38 In addition, patients with mixed connective tissue disease can display many features of SSc along with others of rheumatoid arthritis, myositis, and systemic lupus erythematous.39 The majority of classification criteria require the presence of antibodies directed toward ribonucleoprotein (RNP) to make the diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease.39

Systemic Sclerosis Mimics

There are a broad range conditions which can mimic many of the features of SSc. These include inflammatory or autoimmune diseases (e.g., eosinophilic fasciitis, graft versus host disease, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, scleroedema, scleromyxoedema, diabetic cheiroarthropathy, amyloidosis, and carcinoid syndrome), drug-induced (e.g., aniline-contaminated rapeseed oil [toxic oil syndrome] and L-tryptophan [eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome]), and occupational exposures (e.g., epoxy resins, polyvinyl chloride, radiation fibrosis, and silica).4,37 Furthermore, a number of genetic conditions can mimic SSc, such as stiff skin syndrome and Werner’s syndrome, and can occur as the result of a paraneoplastic phenomenon.4,37

Investigations

The choice of investigations is based upon the clinical presentation. However, many clinicians perform extensive baseline investigations (e.g., HRCT of the thorax to investigate the presence of interstitial lung disease) as these could have important prognostic, and potentially treatment, implications. Patients with SSc require regular cardiopulmonary screening (usually on a yearly basis) with pulmonary function testing with or without conducting a transthoracic echocardiogram to assess for evidence of pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease, and/or if the patient becomes symptomatic during follow-up.40

Autoantibodies

Autoantibodies, especially those that are SSc-specific, are very helpful tools which strongly inform the diagnosis and disease subset of SSc, and have important prognostic implications such as the likely pattern of internal organ involvement. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) test is positive in the majority (~95%) of patients with SSc.41 Furthermore, specific SSc-antibodies targeting a wide range of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins can often be detected including, but not limited to, centromere proteins, topoisomerase 1, and RNA polymerases I-III.42 ANA testing and many antibodies (e.g., anti-centromere) are typically routinely available in hospital laboratories. However, some are currently only available within research settings, such as anti-EIF2B antibodies.42 Various autoantibodies can be observed in patients with overlap syndromes including anti-PM-Scl antibodies (myositis), anti-U1-RNP (myositis and/or systemic lupus erythematous), and anti-SS-A/Ro60 and anti-SS-B/Ro52 antibodies.42 Rarely, SSc-spectrum disorders can also occur in the presence of anti-synthetase (e.g., anti-Jo-1), typically seen in patients with myositis.42

Nailfold capillaroscopy

Nailfold capillaroscopy allows examination of the microcirculation in situ. Low magnification (~x10) devices include the handheld dermatoscope, stereomicroscope, and ophthalmoscope.43,44 High magnification (~x200–600) by videocapillaroscopy is considered the gold standard. Low magnification capillaroscopy allows for a broad, widefield view of the nailfold area and assessment of whether the capillaries are generally normal or abnormal. Normal capillaries have a regular, homogenous, hairpin-like appearance and are evenly distributed. This is reassuring in patients presenting with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Conversely, in SSc and other related disorders there is progressive capillary enlargement (including ‘giant’ capillaries), microhaemorrhages, capillary loss/vascularity, and ineffective neoangiogenesis.45 Such alterations can be seen early (years) before the clinical onset of SSc (e.g., skin sclerosis) and therefore is an important investigation to help make the early diagnosis of SSc. Similar capillaroscopic alterations can also be seen in dermatomyositis (e.g., ramified or ‘bushy’ capillaries).

Other specialist investigations

Infrared thermography (using a thermal camera) is used to measure skin blood flow and can be used to distinguish between primary and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.42 Functional/dynamic vascular assessment can be made through incorporation of cooling and heating challenges. At present, thermography is not widely available outside specialist centres because of the high cost of the equipment, but low-cost mobile devices may allow greater access in the future. Other investigations are dependent on the prevailing clinical picture. For example, cardiac MRI is used for suspected primary SSc heart disease and differentiation of fibrotic or inflammatory damages, as well as breath testing, often using glucose or lactulose as the substrate, for small bowel bacterial overgrowth.

MANAGEMENT

General principles

All patients with SSc should be managed as part of a specialist multidisciplinary team, including colleagues from specialist rheumatology nursing and allied health care professionals such as physiotherapists and podiatrists.46 Patients are increasingly using internet-based information to learn more about their condition and to inform healthcare decisions and should be directed towards appropriate sources of information.47 Patients are often managed under joint/shared care with local rheumatologists. Colleagues from general (internal) medicine are often involved in the care of patients with SSc including during acute episodes of hospitalisation and/or internal organ-based specialists such as respiratory medicine for lung involvement. Surgical intervention is sometimes required, including vascular and orthopaedic surgery. Patients with SSc can become critically unwell including from progression of their organ-based complications and infection/sepsis; the latter of which especially occurs if they are receiving high doses of immunosuppressive medication.48

Pharmacological Management of Systemic Sclerosis

There are a number of effective drug therapy treatments which are used in the management of patients with SSc. Mirroring the complexity of the SSc pathogenesis, broadly speaking (because there is overlap) drug treatments can be generally divided into three groups: vascular-acting, immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory, and anti-fibrotic. Access to treatments may vary between countries, for example because of local reimbursement policies.

Vascular-acting therapies

Vascular-acting (vasodilatory or vasoactive) therapies are central to the management of SSc. Vasodilatory/vasoactive therapies are used in the management of Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers.17 In addition to general, including lifestyle, measures such as keeping warm and stopping smoking, the majority of patients with SSc require pharmacological management for digital vascular disease. These include calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine); in addition, clinicians are increasingly using phosphodiesterase-Type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil) earlier in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon, especially in SSc.17 Other drug treatments include losartan, ACE inhibitors, and fluoxetine, the latter of which is useful in patients prone to vasodilatory side-effects.17 The endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan is licensed in the UK and Europe for the prevention of digital ulcers in patients with severe/recurrent disease ulcer, but it does not impact on ulcer healing.49 Many pharmacological treatments such as PDE5 inhibitors and endothelin receptor antagonists are also used in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. In pulmonary hypertension, sequential or initial combination therapy is superior to monotherapy, offering improved survival.50 Drugs can be used to target the endothelin (e.g., ambrisentan and macitentan), prostacyclin (e.g., selexipag and iloprost/epoprostenol), and nitric oxide (e.g., sildenafil and tadalafil) pathways.51 ACE inhibitors are the first-line pharmacological treatment for the scleroderma renal crisis.33

Immunosuppressive/Immunomodulatory

Immunosuppressive agents (e.g., disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs [DMARD]) that are used in other rheumatological conditions are sometimes also used in the management of SSc. Patients with early diffuse cutaneous SSc should be offered immunosuppressive treatment (e.g., methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil) or more intensive therapy (e.g., intravenous cyclophosphamide).52 Oral drug therapies are usually first-line treatment, with cyclophosphamide offered by some healthcare professionals in patients who are refractory and/or with serious internal organ-based complications such as myocarditis. Mycophenolate mofetil has been shown to be as efficacious as cyclophosphamide for the treatment of SSc-interstitial lung disease and is better tolerated by patients.53 However, for patients who are refractory there is an increasing use of biologics, including rituximab and abatacept,54,55 thanks to preliminary data obtained in patients with SSc and the huge experience of the community regarding their use in rheumatological-related diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Moreover, Phase II-III trials that showed a good safety profile despite not reaching the point of efficacy on primary outcome measures has meant that tocilizumab or abatacept may be offered in refractory patients with an inflammatory profile, in early disease, and with musculoskeletal involvement.

Autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation is a powerful potential treatment option in highly selected patients who are at high risk of severe/fatal disease progression.56,57 Although significant improvement/stabilisation in skin and lung disease can be seen this should not be considered as a cure. Furthermore, there is a notable risk of treatment-related mortality (5–10% according to procedures) which is significantly higher in patients with cardiorespiratory involvement. Therefore, patients undergo extensive cardiorespiratory investigation during transplantation workup. Certain inflammatory complications (e.g., myositis) can benefit from treatment with oral steroid therapy. However, patients need to be closely monitored because of the potentially promoting scleroderma

renal crisis.58

Anti-fibrotic

Therapeutic molecular targets of SSc-interstitial lung disease are being actively researched and anti-fibrotic therapies used for the treatment of idiopathic lung fibrosis are also being investigated in SSc.59,60 Nintedanib was found in a recent Phase III trial to significantly reduce the annual rate of lung function decline (force vital capacity), leading to its worldwide licencing for the treatment of SSc-associated interstitial lung disease.61 The optimal use of the drug still needs to be defined; however, the preliminary data suggest that overt disease, defined by >10% of interstitial lung disease on HRCT, may be appropriate. Moreover, the combination of nintedanib and mycophenolate showed a good safety profile and may represent the most potent regimen to preserve lung function.

Future treatment options and challenges

Increasing understanding of the pathogenesis of SSc has driven the recent flurry of clinical trials for drug therapies for SSc.62,63 However, demonstration of treatment efficacy of drug therapies is a significant challenge. Future studies need to consider the heterogeneity of the disease and important aspects of study design, such as patient selection and the incorporation of novel endpoints of treatment efficacy.64-66

CONCLUSION

SSc is a complex, multiorgan disease which has a high burden of patient morbidity and can be life-limiting. Great advancements have been made in understanding the aetiopathogenesis of SSc. There are a range of effective treatments for many of the internal organ-based complications. Demonstration of treatment efficacy in such a heterogeneous disease is very challenging and future clinical trials will need to address this. Patients with SSc should be managed by a specialist multidisciplinary team, including colleagues from general medicine and organ-based specialists who understand the possible complexities of the disease.