BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Current guidelines provide clinical recommendations for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) treatment,1,2 but there is a lack of knowledge on how patients are treated in the real-world. The authors give an insight into treatment patterns of newly diagnosed patients with asthma, COPD, and asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) syndrome across three electronic data sources, from the Netherlands, UK, and USA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was executed in three databases, namely two electronic health record databases: Integrated Primary Care Information (IPCI), the Netherlands; Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), UK; and one claims database, IBM MarketScan® Commercial Database (CCAE), USA. In each database, mapped to the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (OMOP CDM),3 the authors created three study cohorts by identifying adult patients with a first diagnosis of asthma, COPD, or ACO, respectively. Patients needed to have at least 1 year of database observation time prior to incident diagnosis and 3-year follow-up time.

Treatment episodes were defined as continuous subscriptions from the same respiratory drug class, with a maximum gap of 30 days between prescriptions. A prescription of another drug class was considered a switch if there were fewer than 30 days overlap, with the previous drug class and a combination therapy otherwise. Results were visualised with sunburst plots.

RESULTS

The authors identified a total of 566,168 patients with asthma, 115,971 patients with COPD, and 96,985 patients with ACO across the databases. Approximately one-third of the patients with asthma start with short-acting β-agonists followed by inhaled corticosteroids (in Europe) and systemic steroid bursts (in the USA).

In Europe, patients with COPD start more often with long-acting muscarinic antagonist than patients with asthma.

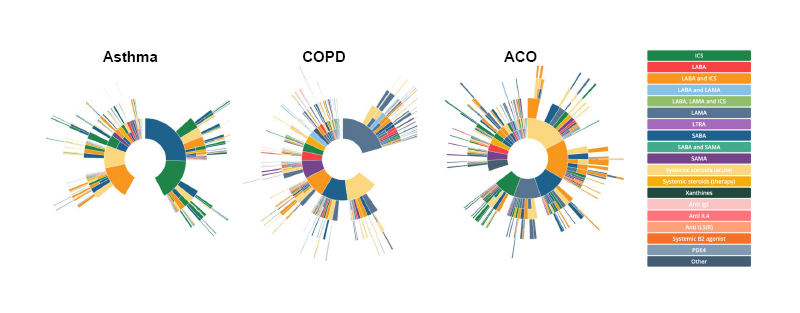

In the USA databases, treatment for asthma and COPD are comparable and systemic steroids are frequently used as first treatment. Patients with ACO most often receive treatment, and the differences are smaller between the USA and Europe. Results for one of the databases (IPCI) is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sunburst plots of treatment patterns of adult patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, in the Netherlands (Integrated Primary Care Information database), showing the first treatment in the centre, and subsequent treatments in the surrounding outer layers.

Each colour represents a drug class and a layer with multiple colours indicates a combination therapy.

ACO: asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting β-agonist; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LTRA: leukotriene receptor antagonists; PDE4: phosphodiesterase-4; SABA: short-acting β-agonist; SAMA: short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

CONCLUSION

The authors conclude that treatment patterns in the real world vary across countries, with substantial differences in first treatments, suggesting deviation from global guidelines