INTRODUCTION

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) causes small and medium-vessel destruction. The 2012 revised Chapel Hill Consensus1 describes three main types of AAV: microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) aims to arrest disease progression, whilst minimising the risks of immunosuppression by advocating treatment with rituximab and intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide.2

AIMS AND METHODS

We reviewed the management of patients with AAV in our respiratory clinic until March 2015, comparing our management with BSR guidelines. We investigated morbidity data and long-term outcomes for patients.

RESULTS

The study involved 30 patients with GPA, 15 with MPA, 5 with EGPA, and 2 who had unclear diagnoses. The lungs, kidneys, and upper respiratory tract were the most commonly affected areas. Glucocorticoids and IV or oral cyclophosphamide were the mainstay drugs used for induction. Prednisolone and azathioprine were most commonly used for maintenance. No patients with EGPA relapsed; 5 patients with MPA relapsed, including 2 who relapsed whilst on-drug. One of these patients had IV methylprednisolone induction and 1 was given oral prednisolone and rituximab; these patients were maintained at relapse with the use of prednisolone and prednisolone/ rituximab, respectively.

In addition, 10 patients with GPA relapsed, of whom 2 experienced two relapses. Eight of these relapses were on-drug and the mean time to relapse was 32.3 months. For patients who relapsed on-drug, the methods of induction included 3 patients with IV cyclophosphamide, 2 with prednisolone/cyclophosphamide, 1 with prednisolone, 1 with IV cyclophosphamide/rituximab, and 1 with prednisolone/cyclophosphamide/rituximab. Maintenance therapies used before relapse included 5 patients treated with azathioprine/prednisolone, 2 with mycophenolate/prednisolone, and 1 with prednisolone only.

DISCUSSION

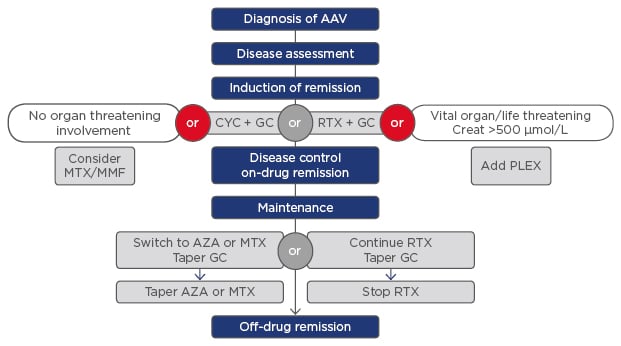

Figure 1 shows the treatment guidelines for AAV. The CYCLOPS trial showed the non-inferiority of treatment with pulsed IV cyclophosphamide, with a less cumulative dose (to reduce urothelial toxicity) and fewer instances of leukopenia;3 however, the relapse rate was higher.4 We reported no cases of haemorrhagic cystitis; however, 1 patient induced on oral cyclophosphamide developed bladder cancer.

Figure 1: The treatment guidelines for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

AAV: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis; AZA: azathioprine; CYC: cyclophosphamide; GC: glucocorticosteroids; MMF: mycophenolate; MTX: methotrexate; PLEX: plasma exchange; RTX: rituximab.

Six, two, and one patient(s) with GPA, MPA, and EGPA, respectively, had refractory disease, and therefore a secondary rituximab induction was added. One GPA patient subsequently relapsed. One patient with GPA and another with MPA relapsed after primary rituximab induction.

The RAVE trial5 demonstrated the non-inferiority of a shorter induction with rituximab at 18 months compared to prednisolone/cyclophosphamide induction with maintenance using azathioprine. Rituximab treatment resulted in reduced immunosuppression overall and was more likely to be successful in inducing remission in relapsing disease, particularly in proteinase 3-AAV.6 Six patients on rituximab developed hypogammaglobulinaemia and 5 experienced B cell depletion. There is a ˜25% risk of hypogammaglobulinemia associated with rituximab use.

Two patients developed an aspergillus infection and 1 presented with cytomegalovirus colitis whilst immunosuppressed. The highest mortality from infection is within the 1st year of treatment, when immunosuppression is maximal. Infection independently predicts early mortality, and respiratory tract infection is especially problematic. In addition, 1 patient with EGPA died from pneumonia and pseudomembranous colitis and 5 patients in the MPA group died (1 with vanishing duct syndrome from cyclophosphamide treatment, 1 at index from respiratory and renal failure, and 1 due to a perforated colon), compared to 2 patients with GPA (1 with granulomatous aortic valve stenosis and heart failure).

Aggressively treating active disease limits the irreversible damage caused by the condition. Furthermore, it is also important to minimise immunosuppression via relapse prevention. However, immunosuppression can be as problematic as AAV itself. Use of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score is recommended to measure active disease, with remission defined as a Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score of 0. The Vasculitis Damage Index measures the irreversible damage caused by both the disease process and immunosuppression. By using the above scores, we will be able to differentiate pre-existing irreversible damage from new activity, thereby reducing cumulative immunosuppression and its side effects.