Abstract

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is one of the main causes of death on the waiting list. Liver transplantation (LT) is the only curative treatment for patients with ACLF and therefore it should be considered in all cases. However, the applicability of LT in patients with ACLF is challenging, given the scarcity of donors and the high short-term mortality of these patients. Organ allocation has traditionally been prioritised according to the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) system. However, the accuracy of MELD score is limited in patients with ACLF. In this article, the authors review the outcomes of patients with ACLF before and after LT, highlighting its clinical course, the feasibility of LT in the sickest patients, the role of the organ allocation system, and possible indicators of futility.

INTRODUCTION

The natural history of patients with cirrhosis is characterised by the development of acute decompensating events that negatively impact their prognosis.1,2 Even though liver transplantation (LT) is its only curative treatment, access to it is limited because the demand for organs exceeds the availability.3

During the last decade, it became apparent that not all acute decompensating events have the same impact in patients with cirrhosis. On the one hand, decompensations can lead to the development of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a syndrome characterised by the development of organ failure and a high short-term mortality.4 On the other hand, this syndrome is clinically and pathophysiologically different from mere acute decompensation, which possesses a much more favorable prognosis.5 ACLF may occur at any stage during chronic liver disease, from compensated cirrhosis to advanced decompensation.6

From a pathophysiological point of view, although both ACLF and mere acute decompensation share the same triggers, the former is characterised by the presence of an intense systemic inflammatory response.6 Patients with ACLF exhibit features of systemic circulatory dysfunction, such as high plasma levels of renin and copeptin, and high concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, which vary according to the precipitating event and correlate with the clinical course of the syndrome.7 All these events lead to organ failure through direct deleterious effects on microcirculatory homeostasis, mitochondrial function, and immune damage.5,8

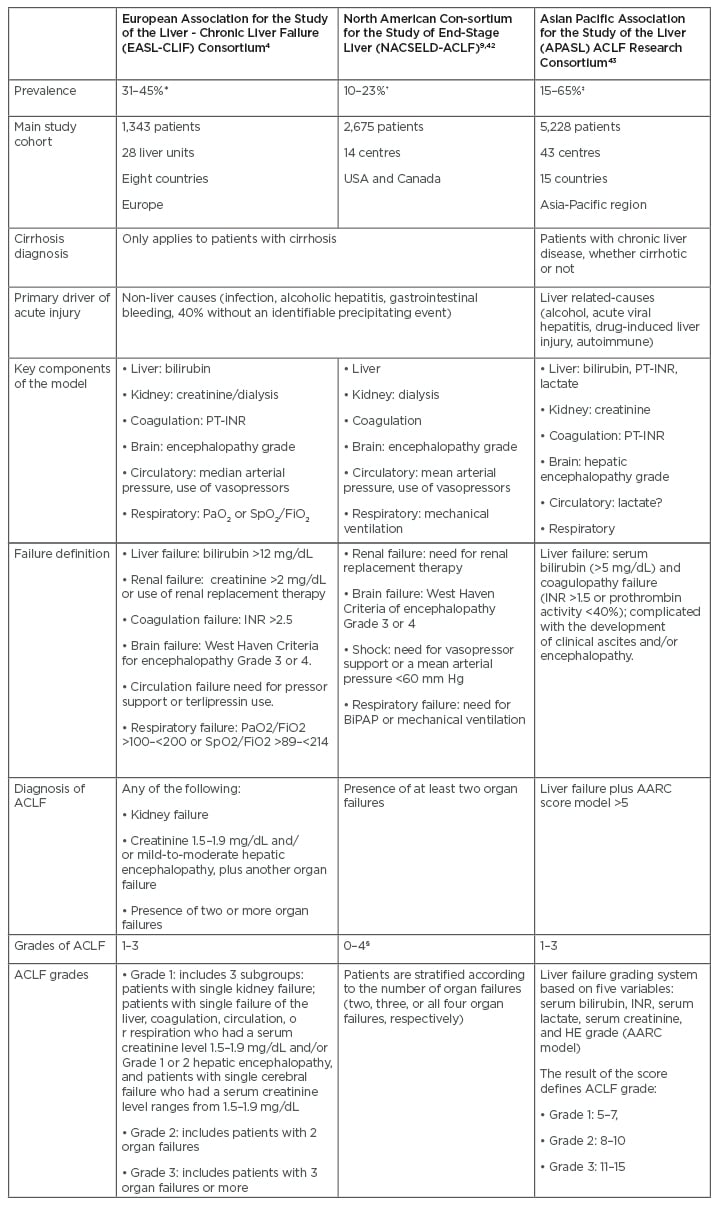

Over the last decade, different definitions of ACLF have been proposed (Table 1). Depending on which definition is applied, significant differences are observed in the prevalence and incidence of ACLF. Based on the European Foundation for the study of chronic liver failure (EF-Clif) definition, the prevalence of ACLF is 23% in patients admitted for acutely decompensated cirrhosis.4 Additionally, the in-hospital incidence was reported to be 11% in those patients who do not fulfill ACLF criteria at admission.4 Overall, approximately one-third of patients hospitalised for acute decompensation develop ACLF during hospitalisation.4 Nevertheless, when the American definition of ACLF was applied in a North American cohort, less than 40% of patients who met European criteria were captured by The North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) criteria.9 Table 2 compares the estimated mortality according to the three main consortium definitions.10

Table 1: Prevalence and definitions of acute-on-chronic liver failure according to the three main consortiums.

*Estimated over patients hospitalised for acutely decompensated cirrhosis.

†Estimated over patients with acutely decompensated cirrhosis precipitated or not by infection.

‡Estimated over patients with a first episode of acute liver deterioration due to an acute insult directed to the liver.

§Number of organ failures.

AARC: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of Liver Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Research Consortium; ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; BiPAP: bilevel positive airway pressure; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; HE: hepatic encephalopathy; INR: international normalised ratio; PaO2: partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PT-INR: prothrombin time and international normalised ratio; SpO2: oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry.

CLINICAL ASPECTS OF ACUTE-ON-CHRONIC LIVER FAILURE

ACLF is a highly dynamic syndrome.4 Although it is associated with elevated mortality, a significant proportion of patients reverse the organ failures and recover. Therefore, Gustot et al.11 proposed to assess the evolution of ACLF at 3–7 days, considering that it correlates better with short-term prognosis. While there may be variability, approximately one-half of the patients who are admitted with Grade 1 ACLF resolve it. This is less frequent in patients with Grade 2 or 3 ACLF, in whom reversal or improvement to a lower grade is estimated to occur in 35% and 16% of individuals, respectively.11 In contrast, progression to higher grades has been reported in 21% and 51% of patients with Grades 1 and 2 ACLF, respectively. The worse outcomes are expected in patients with Grade 3 ACLF because approximately 70% do not improve over time and 80% die at 90 days.11

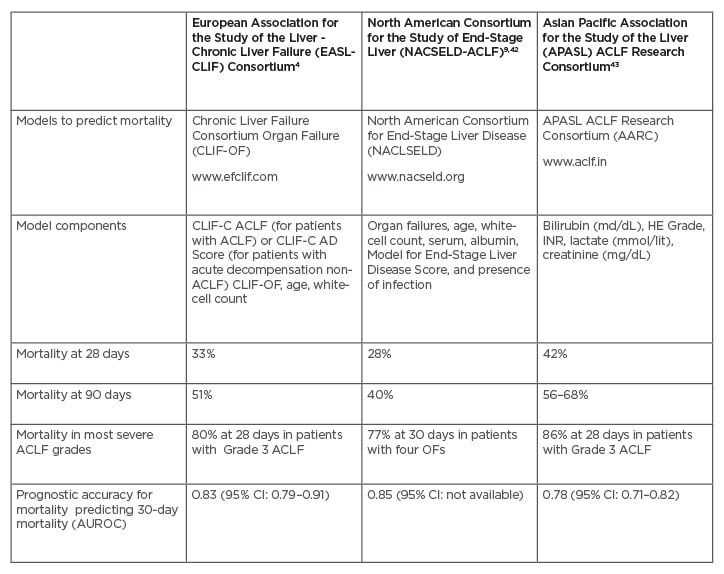

Table 2: Mortality of patients according to the three main consortium definitions.

ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic; CI: confidence interval; OF: organ failure.

Recently, Trebika et al.12 described three different clinical courses in patients admitted for acute decompensation without ACLF. The first one, which was termed ‘pre-ACLF’, constituted patients who developed ACLF within 90 days from the acute decompensating event. The second one, termed ‘unstable decompensated cirrhosis’, was characterised by readmissions but without the development of ACLF. The third one, represented by patients without readmissions or development of ACLF, was termed ‘stable decompensated cirrhosis’. The three clinical courses showed different pathophysiology and prognosis, as well as variability in the degree of systemic inflammation. This classification could guide the selection of the most appropriate setting for patient management and guide the decisions regarding the urgency of LT. 12

Finally, it is important to highlight that, although a greater number of organ failures is associated with higher mortality, it has recently been shown that certain organ failures, such as those of extra-hepatic origin, can have a negative effect on the prognosis, independently of the ACLF grade.13

ROLE OF LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN PATIENTS WITH ACUTE-ON-CHRONIC LIVER FAILURE

ACLF can occur in patients who are already listed for LT or be the reason why they are listed. It was reported that 31% of the patients undergoing liver transplantation with ACLF were already on the waiting list when this syndrome developed.28

The CANONIC study was the first to report the outcomes after LT in a select and reduced group of patients with ACLF. The study estimated a 1-year post-LT survival of 75% in comparison to a mortality of 23% in those patients who were not transplanted.4 Subsequently, numerous studies evaluated post-transplant survival and complications at 30 days, 90 days, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years.14-19 According to a recent meta-analysis, including 22,238 patients with ACLF and applying the European definition, the 1-year post-LT survival was 85% in those patients who were transplanted and 28% in non-transplanted patients. When analysing patients who were transplanted with ACLF and those who were transplanted without ACLF, the 1-year survival was 86% and 92%, respectively. Similarly, the 5-year post-LT survival was 67% and 81%, respectively.20

The experience of LT in patients with ACLF is increasing worldwide, positioning it as the only curative treatment. Nevertheless, the available data is heterogeneous and it is unclear whether LT is beneficial in very sick patients with extra-hepatic organ failures.15-17 Although there is no precise definition to define LT futility, experts from European and American societies consider that post-transplant survival should be greater than 50% at 5 years.21 However, in daily practice, several challenges are faced regarding how to quickly identify which patients with ACLF will benefit from LT, what is the precise time to LT, and how to select the appropriate donors.

Even though the presence of extra-hepatic compromise, such as circulatory, respiratory, or brain failure, is associated with lower transplant-free survival than coagulation and liver failure, there is agreement across scientific societies that patients with ACLF Grade 1 and 2, as well as those patients who have recovered from an ACLF episode, should be listed for LT.22 However, LT for patients with ACLF with three or more failing organs (ACLF-3) is still controversial, and will be discussed in the following section.

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN PATIENTS WITH GRADE 3 ACUTE-ON-CHRONIC LIVER FAILURE

The presence of ACLF-3 should not be considered a contraindication for LT. To date, the greatest challenges that LT presents in these patients are represented by its timing and with the donor selection process, which should ensure that the principles of utility and beneficence are fulfilled.23 Of note, recent studies demonstrated that the presence of ACLF does not negatively impact post-transplant survival and also has no impact on long-term complications, such as chronic kidney disease.17 However, patients with ACLF-3 were shown to have greater use of hospital resources, longer hospitalisations, and intensive care unit stays.19,20

In practice, many centres may not offer LT to patients with multi-organ failure, given that some of them might have lower post-transplant survival than expected.24 However, in a retrospective cohort study published by Artru et al.,14 a 1-year post-LT survival of 84% was reported in patients with ACLF-3. This study was the first to demonstrate excellent 1-year post-LT survival outcomes among these very sick patients. However, it should be noted that individuals in this study who were transplanted with ACLF-3 were selected carefully.14 More recently, analysis of the North American Registry of the United Network Organ Sharing (UNOS) presented similar results, estimating a 1-year post-LT survival of 82% in the same population.19

Additionally, two more recent studies evaluated post-transplant outcomes in ACLF-3 patients. The first one, published by Thrulavath et al.,25 demonstrated in a large sample the feasibility of LT in patients with multi-organ failure. In this study, the 1-year post-LT survival was 81%, even in patients with more than three organ failures. Although patients with respiratory failure showed lower post-transplant survival, it was estimated to be 79% at 1 year.25 The second study evaluated long-term outcomes after LT and reported that patients with ACLF-3 at the time of LT had a 5-year survival greater than 50%. Of note, mortality in these patients occurred predominantly during the first year and plateaued thereafter, reaching similar rates to those with lower ACLF grades. The main causes of death after the first year were infection and malignancy.19

ISSUES REGARDING FUTILITY IN LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

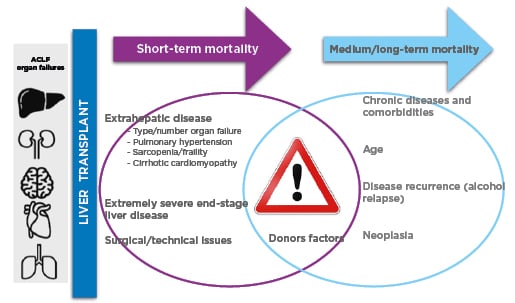

As mentioned, there is agreement that LT in patients with single organ failure or two organ failures (ACLF-2) is associated with favourable outcomes. Even though good results were shown after LT in patients with ACLF-3, a subgroup of patients might be too sick to benefit from it.23 Given the shortage of donors, the early timing of LT, the donor quality, and the likelihood of spontaneous recovery are important elements that should be considered (Figure 1).24,27

Figure 1: Main drivers of mortality after liver transplantation.27

Studies of LT and ACLF-3 include heterogeneous populations. Optimising survival after LT involves several factors in addition to the presence of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Some of them have relevance in the short-term post-transplant mortality, such as the type and number of organ failures at the moment of LT, the presence of sarcopenia/frailty, pulmonary hypertension, and the presence of myocardial dysfunction. Other factors are relevant for the medium/long-term outcomes, such as other comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease), disease recurrence (e.g., alcohol relapse, deficit of adequate nutritional and physical activity planning), and oncological diseases. The type and quality of the donor organ, as well as the timing to accept it, can have an impact at any point in the post-transplant. Even though the current scores might help predict short-term and long-term post-transplant mortality, there is still a place for its improvement. It seems that the CLIF ACLF score is an accurate tool to predict survival without LT but is suboptimal to predict outcomes after LT.

ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; CLIF: Chronic Liver Failure; ESLD: end-stage of liver disease; LT: liver transplantation.

The controversy arises because several studies reported poor post-transplant outcomes in patients with ACLF-3, which might be driven by the haemodynamic instability and the requirement for mechanical ventilation at the time of LT.16,19,24 With the purpose of identifying patients who might have a poor post-transplant prognosis, Sundaram et al.19 reported that a donor risk index greater than 1.7 was associated with greater mortality while LT within 30 days of listing was associated with greater survival.Additionally, in an abstract presented at The Liver Meeting 2020, held by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), a dynamic model was designed in order to determine the ideal timing regarding when to stop waiting for an optimal quality donor and accept a marginal quality organ.27

In a larger UNOS registry study, the improvement of patients with ACLF-3 at listing to ACLF 0–2 at transplantation enhanced post-LT survival, particularly in those who reversed the circulatory or brain failures or who were weaned from the mechanical ventilator.29 This study also showed that patients transplanted after improving or resolving ACLF had greater post-LT survival than those who underwent LT with ACLF Grade 3.29 However, less than 25% of the patients with ACLF-3 on the waiting list improved the degree of ACLF. Therefore, even though it seems that it would be advisable to perform the LT after recovering organ failures, this might not be possible for the majority of patients with ACLF-3.29

Meanwhile, Artzer et al.30 were the first to publish a LT futility score for patients with ACLF-3 (transplantation for ACLF-3 model [TAM] score), which was generated from a retrospective, multicentre cohort study of five European centres. The score includes arterial lactate, mechanical ventilation support, white blood cell count, and age, and proposed a cut-off point that predicted a survival probability of less than 10%.

Overall, prospective data from large multi-centre studies are needed in order to resolve the controversy surrounding LT in these very sick patients. There is a great expectation with the prospective CHANCE study (‘Liver Transplantation in Patients with Cirrhosis and Severe Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Indications and Results’), which is directed by the EF-Clif and will begin enrolment in 2021.31 The main aim of this study is to compare 1-year graft and patient survival rates after LT in patients with ACLF-2 or -3 at the time of LT with those patients with decompensated cirrhosis without ACLF, and also with transplant-free survival of patients with ACLF-2 or -3 not listed for LT.

LIMITATIONS OF THE MODEL OF END-STAGE LIVER DISEASE ALLOCATION SYSTEM

The model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) and MELD plus serum sodium (MELD-Na) allocation system has improved the outcomes of patients on the waiting list.32,33 Patients with higher MELD and MELD-Na scores are at increased risk of ACLF. Additionally, they might predict survival in these patients.34,35 However, none of these models incorporate determinations that represent brain, circulatory, or respiratory failure. Furthermore, they do not include biomarkers of systemic inflammation, which appear to correlate with outcomes in patients with ACLF.36

According to a publication by Sundaram et al.,27 the probability of dying or being removed from the waiting list was higher in patients with ACLF-3 than in patients with acute liver failure (Status 1A in the USA). Later, a publication from the same group documented several interesting findings.20 Firstly, in patients with ACLF-3, the MELD-Na score tended to underestimate 90-day mortality in the waiting list.20 Secondly, the proportion of patients with ACLF-3 and MELD-Na less than 25 who died or were removed from the waiting list at 28 and 90 days was 44%.20 This was significantly higher than what was observed in patients with a MELD-Na score greater than 35 without ACLF.20

Another interesting study that evaluated the performance of MELD-Na to predict 3-month mortality in patients with ACLF was published by Hearnaez et al.37 The authors reported that MELD-Na does not fully capture the prognosis of patients with severe ACLF. Interestingly, MELD-Na was the main determinant to consider listing for LT, even in patients with ACLF-3. Approximately 65% of patients with ACLF had a MELD-Na score less than 30, suggesting that these patients have a disadvantage in the current allocation system.36 Of note, the authors considered both the European and American definitions for the analysis and supported a possible superiority of the former.

Given the limitations of the MELD-Na score for organ allocation, new prognostic scores have emerged specifically designed to assess the risk of mortality in patients with ACLF. The CLIF-C ACLF score computes organ failures, age, and white blood cell count.38 The CLIF-C ACLF score showed greater accuracy in predicting mortality than the MELD and MELD-Na; however, external validation in a prospective multicentre cohort is desired (Table 2).37,38 Moreover, the NACSELD validated a score as a predictor of inpatient mortality (NACSELD ACLF score).39 This score, which defines extra-hepatic failures by clinical intervention (e.g., the requirement for mechanical ventilation, the use of vasopressors, or renal replacement), could predict better survival. Therefore, experts suggest that the decision to allocate LT in patients with ACLF may ultimately be guided by the CLIF-C ACLF and NASCELD ACLF scores because they might have a greater ability to predict wait-list mortality and post-transplant survival.40 Developing a scoring system that captures essential donor and recipient factors, such as organ failure, global nutritional assessment, physical performance, and chronic conditions, is desired. This could ultimately direct a more individualised allocation approach.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS: WHAT’S NEXT?

Significant advances in the understanding of the role of LT in patients with ACLF have been achieved over the last years; however, there are still various unanswered questions. Even though LT is recommended for these patients, only one-third of the patients with ACLF-3 access LT. In this regard, performing the LT in a timely manner is challenging. Additionally, an in-depth pre-transplant evaluation of these patients might be infeasible, particularly when they present with multi-organ failure.

Most evidence concerning ACLF and LT arose from retrospective studies with important selection bias. This bias originated because patients with ACLF who were not transplanted were not analysed, among other methodological issues. Therefore, a prospective approach such as the CHANCE study might overcome these issues.

On the other hand, there is a need to develop tools to predict the development of ACLF, particularly in patients on the waiting list. Modern concepts such as sarcopenia and frailty, as well as the role of biomarkers such as cystatin C or N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, deserve further evaluation. Additionally, the role of hepatic encephalopathy and the influence of bacterial and fungal infections might help predict outcomes on the waiting list and could aid in prioritising patients.13,28,41

CONCLUSIONS

ACLF is a highly dynamic syndrome that, with specific criteria and proper timing, can benefit from a LT. The early identification of a window of opportunity for LT, the aggressive treatment aimed to reverse organ failures, and the judicious selection of donors have a significant impact on the waiting list and post-transplant outcomes. Until more evidence arises from prospective studies, LT teams will face challenges in dealing with these very sick patients, particularly when balancing the risks and benefits of LT and its timing.