The US passed the Orphan Drugs Act in 1983, then the Rare Diseases Act in 2002, but there is still a way to go in driving drug development for the most uncommon conditions. What new regulations are needed worldwide to address the lack of treatments for rare diseases?

Words by Danny Buckland

While most anniversaries spark cause for celebration, some milestones must be seized as an opportunity to reflect and take stock. The US transformative Orphan Drugs Act (ODA) turns 40 soon, and next year the Rare Diseases Act (RDA) will have been around for 20 years – but both need an overhaul to keep pace with advances in science and technology. And the same goes for similar legislation within the UK and EU.

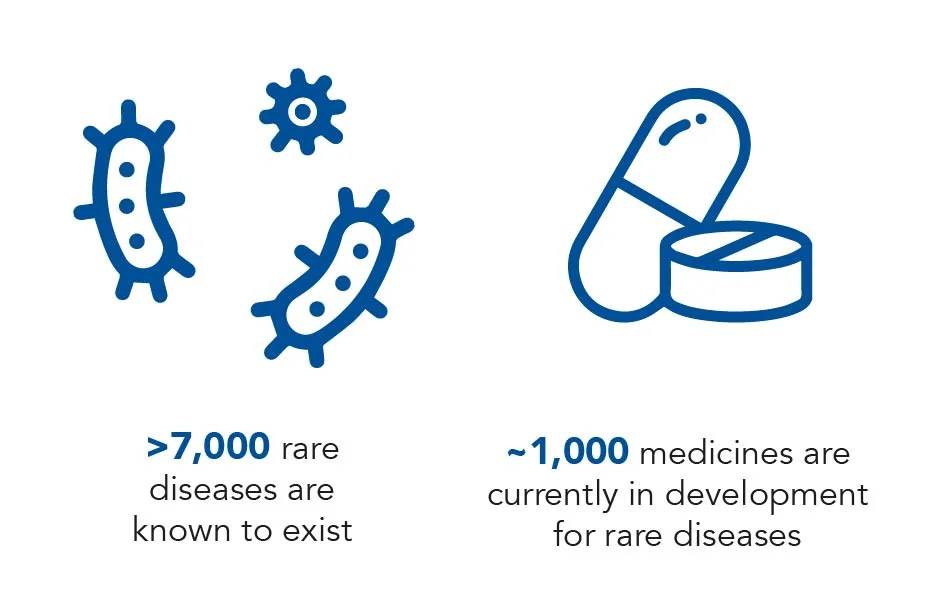

The ODA and RDA revealed a treasure trove of possibilities for pharmaceutical companies, such as financial incentive for developing treatments for rare diseases – those affecting fewer than five in 10,000 people – and access to these treatments for patients. However, for all the ODA and RDA’s impact, the statistics of rare diseases remain troubling. Some 300 million people worldwide are living with one of more than 7,000 rare conditions, yet only 6% of them have an effective treatment. In addition, the fact that these two acts were conceived before the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003 demonstrates that there are further factors to consider.

In Europe, the key EU Orphan Regulation of January 2000 acted as a springboard for drug discovery that helped 199 orphan drugs win approval. And now, there is a gathering momentum for change and hope. Frameworks and regulations around the world are being recalibrated to take advantage of the fresh genomic understanding – 80% of rare diseases are genetic – that is helping to decode complex conditions that confound medicine.

A group of countries is pressing for a United Nations resolution to stimulate research efforts, enhance public health policy, liberate funding and improve quality of life across a spectrum of social factors. Anders Olauson, Chair of the NGO Committee for Rare Diseases, launched a call to action on Rare Diseases Day in July 2021, stating: “Can we do better and more for persons living with a rare disease? The answer is easy and concrete: yes. We can send a strong collective message to our community by adopting a UN resolution.”

The movement to improve frameworks has been strengthened by the ‘Rare 2030’ foresight study, which aims to unite patients, practitioners and key opinion leaders to influence future policy and legislation in Europe. “There is a need to revisit legislation and that is already happening,” says Anna Kole, Rare 2030 Project Lead and Public Health Policy Director, European Organisation for Rare Diseases (EURORDIS) – an alliance of 974 rare disease patient organisations in 74 countries. “We have had a number of consultations about improvements and, although people living with rare diseases aspire to have curative treatments, we have to recognise that it is not all about drugs. The road to curative solutions is long, but there are a lot of other things that could be happening, and efforts need to be coordinated.”

There is a need to revisit legislation and that is already happening

Regulations and legislation are flexing to improve outcomes across the clinical and social landscape. The European Reference Networks, launched in 2017 to improve the treatment of rare diseases by linking 900 highly specialised healthcare units from 300 hospitals in 26 EU countries, are continuing to encourage collaboration. In addition, The European Pillar of Social Rights is paving the way for social rights, opportunity and inclusion for people living with rare diseases to be enshrined in law.

In the UK, the four nations are working on action plans that will energise research and power a new era of care. “There is potential for a new landmark rare diseases framework, but how much of a landmark it is depends on how ambitious plans are when they are published next year,” says Nick Meade, Joint Interim Chief Executive and Director of Policy, Genetic Alliance, which represents organisations supporting the 3.5 million people living with genetic, rare and undiagnosed conditions in the UK. “There is so much opportunity on the table at the moment and we need to achieve meaningfully different outcomes for people living with varying genetic conditions. There is an avalanche of cell and gene therapies coming after decades of hard work, and we need policy to match that scientific potential.”

EURORDIS highlights that 31% of rare disease patients in Europe have never received treatment for their condition. However, the organisation believes more is possible, and that the COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the potential that arises from regulatory flexibility and collaboration. Denis Horgan, Executive Director, European Alliance for Personalised Medicine, calls for greater harmony in strategic planning and a “conducive regulatory environment” for the development of orphan drugs.

It is clear that the case for change has been made, but how individual countries build new legal and regulatory mechanisms that function across trials, reimbursement and incentives, as well as how they synchronise globally, will be critical to the 30 million people in Europe living with rare diseases. Scientists, research institutions and pharmaceutical companies are raring to go, and patients are infused with fresh hope. The spotlight now falls on policy and law makers to ensure they have the best chance of success.