Over the past two centuries, the landscape of pharmaceutical marketing has transformed almost beyond recognition. We reflect on the propelling reasons behind such metamorphic change and consider the impact of emerging platforms: from print to radio and from TV to online

Words by Michaila Byrne

‘How will I peddle my product and make it stand out against the competition?’

It’s an age-old quandary pondered since time immemorial. If we trace the breadcrumbs back far enough, the contrast between the current pharmaceutical marketing model and earlier frameworks is so stark that these antithetical worlds become difficult to reconcile. As big pharma’s generous budget unanimously confirms, targeting is a blatant strategic imperative. It’s important to reflect on this striking shift and assess the motivations for evolution as well as the subsequent implications for marketers over time.

The early days

Imagine a scenario in which drugs are freely concocted, patented, and marketed – unchecked and with impunity to make any unsubstantiated claims leading to dire and even fatal consequences. Alas, this dystopian-sounding state-of-affairs is not absurd as it sounds. At a time when scientific rigour was yet to be established during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the lines between the chemical and pharma industries were blurry and posed a serious threat to public health.

Mutlu Gunenc, Head of Marketing, Kiadis Pharma reflects: “…regulations have intensified due to informed patients demanding better treatment… the industry has been transforming its business models to meet their external stakeholders’ (physicians, payers, patients, policymakers) needs.’’

By virtue of this freewheeling conduct, journalistic exposés on the subject prompted tighter regulatory rules. This would cement the status quo for generations to come, ushering in a new age of pharma marketing. For a long time, fraudulent intent still had to be proven, but stricter external regulatory bodies began requiring ingredients, side effects, and effectiveness to be outlined in all drug ads.

By the end of the 1950s, 90% of big pharma marketing was targeted at doctors and in the 1960s, control of advertising was passed onto regulatory bodies. Cheap, generic drugs could no longer be marketed as expensive new ones under the guise of different names.

1980s-early 2000s

Rich Quelch, Global Head of Marketing, Origin Pharma Packaging, assesses this shift. “Interestingly, the 1980s saw the most transformational changes to medical marketing, brought about by the political and cultural ethos of the era which was more in support of big pharma as a consumer industry and empowering patients to make their own healthcare decisions.’’

Spearheading the direct-to-consumer marketing movement in the 1980s were Pfizer and Eli Lilly advertising medications treating hair loss, erectile dysfunction, and depression on television networks and radio stations. In 1983, Merck ran the first ever major modern direct-to-consumer TV ad for a prescription painkiller and further controls gave rise to regulation-exempt reminder and help-seeking ads.

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, 66% of American adults and >50% of all Europeans go online to research their conditions before consulting doctors. Reliance on the internet as the conclusive fountain of information has prompted pharma marketers to increase their presence on digital channels. In 2009, regulators began warning pharma companies against buying sponsored search engine links, stipulating that online links must include either the drug name or purpose, but not both.

“Classical communication channels like TV and radio have been very limited because there is a risk that pharma companies might share misleading information with patients, and you cannot control who is watching or listening to these channels. On online platforms however, it is easier to control the content, which means companies can still stay compliant with regulations,’’ says Gunenc.

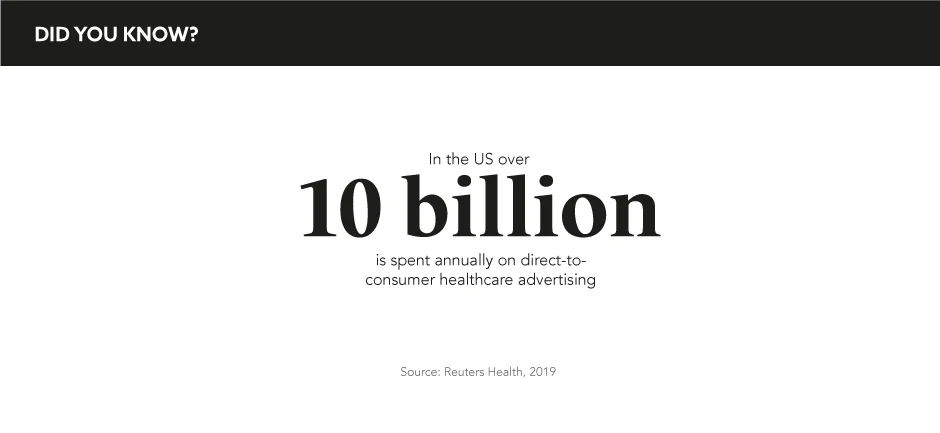

Excluding the 2008 financial collapse and subsequent economic slowdown, direct-to-consumer marketing’s record has shown significant upwards momentum, surpassing all other platforms. The debate surrounding this method continues.

‘‘This is advantageous for consumers if you ask pharma manufacturers, as it educates them about different drug options, encourages them to engage with healthcare professionals and in turn, reduces under-diagnosis of medical conditions. This, they would argue, ultimately saves lives. However, critics have the opposing view that direct-to-consumer marketing leaves patients misinformed as ads overemphasise the health benefits, leading to unnecessary or overprescribing. It can also put a strain on doctor–patient relationships if a prescription is refused,’’ says Quelch.

Here and now

Today, pharma marketing is dipping its toes into the digital pool by utilising apps, social media communities, and mobile ads. ‘‘Social media presents opportunities for pharma to partner with respected industry influencers to boost brand awareness and educate the public in a more authentic way than paid offline advertising ever could,’’ continues Quelch.

Marketing in pharma has also begun deploying advanced analytics to generate potential patient profiles and understand prescribing behaviour that accurately targets providers.

‘‘Data-driven online marketing is, for the first time, allowing pharma companies to target and personalise messages to different audiences, increasing the chances of positive engagement, sales interactions, and brand loyalty,’’ says Quelch.

The nature of drug marketing as we understand it today vehemently jars with its origins. As times have changed, pharma has adapted alongside changing the platforms and restrictions and as such, the marketing landscape has been fundamentally overhauled.

In our hyperconnected world, the essence of a brand must be consistent for all customers, wherever they are