While the potential of cell and gene therapies (CGTs) is huge, the high cost raises concerns from payers. We explore how the industry can drive the adoption of CGTs to ensure that they reach patients around the world, rather than just those in private markets

Words by Michaila Byrne

Commercial space flight is by all accounts the next step in the aviation industry, but when it comes to medicine’s next frontier, all eyes are firmly fixed on cell and gene therapies (CGTs). Vastly superior to conventional medicines since they target the very root of diseases, CGTs are truly the next step in personalised medicine; one-time treatments that can repair and enhance cells at the genetic level. How can the pharmaceutical industry overcome the unique challenges of CGTs to guarantee future access and affordability both in private and public markets?

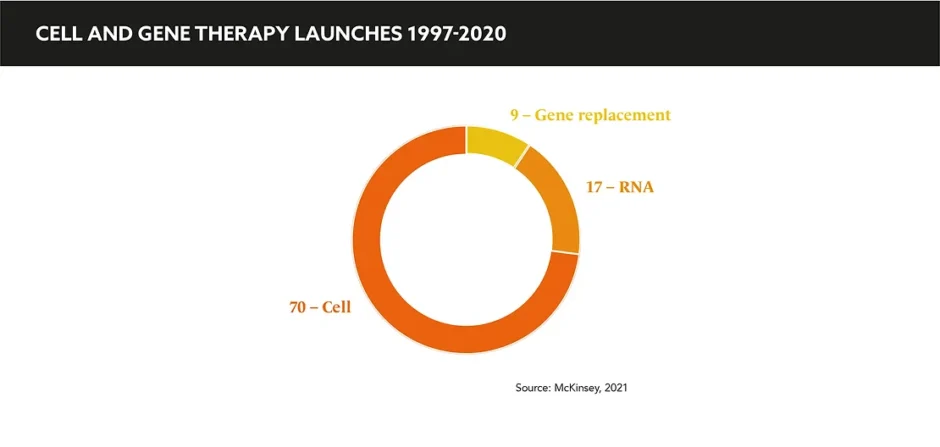

Both significant investments in and rapid innovations from big pharma and smaller biotechs have been funnelled into CGTs. With examples of several treatments blazing a trail toward regulatory approval, precedent has been set alongside a huge pipeline of upcoming therapies, primarily in rare diseases.

“The early years of CGTs have been a bit of a rollercoaster, dominated by excitement and a lot of investment in the field… In the last few years, the field is really starting to come into its own, with advances in technology and new commercial arrangements coming into play to help these life-changing treatments reach patients, many of whom had little or no treatment option before,” says Matthew Hare-Scott, Director, Strategic Media, Porter Novelli. “One of the things that make CGTs so exciting is not just the scientific innovation, but that they are challenging the traditional operating model of the pharma industry and forcing the erosion of longstanding silos, barriers, and rules of engagement.”

To date, the majority of launches have been in rare to ultra-rare patient populations where the unmet need is distinctly high and the affected populations small; this is a large part of the reason behind the general tolerance of higher prices, at least for first generation therapies. Smita Sealey, Associate Partner, ZS Associates echoes this enthusiasm for the future of personalised care: “How do you put a price on a medicine that could potentially cure or give someone their life back? Many of the CGTs to-date launched with a promise of potential cure and the opportunity to replace other high cost therapies, but with much higher value.”

How do you put a price on a medicine that could potentially cure or give someone their life back?

This ongoing question of cost-effectiveness has long been a sensitive area for CGTs since it requires the quantification of value, not just for the patient, but for their loved ones, and broader society. Hare-Scott also notes considerable reluctance from payers and regulators: “Significant barriers need to be addressed before the full potential of these treatments can be realised and scaled up.” He cites the main challenges as: “quite simply, rigid and risk-averse regulatory and payor systems, who are intrigued by the potential of gene therapies but not yet prepared to shoulder the financial risk of these treatments.”

As is the case with much of modern technology, the science has been rapidly advancing, but healthcare infrastructures, pricing systems, and regulatory frameworks have not managed to keep up the same pace. “There is currently limited reward for innovation within the bounds of affordability, budget impact, and cost effectiveness in the absence of evidence to back up a ‘cure’, and for manufacturers this is a tall order from an evidence development perspective, especially since regulatory pathways are built to accelerate commercialisation even in the absence of hard data that payers warrant,” says Sealey.

The high cost of CGTs is often justified by offsetting the lifetime costs of most disease treatments with an alternative of a one-off payment. Hare-Scott highlights: “However, while one-off payments can be accepted when there are few patients, such as those with rare or ultra-rare conditions, two thirds of the pipeline for CGTs target diseases that are not rare.”

The solution behind such expensive therapies is a timeless formula: communication, collaboration, and mindset; moving the dialogue beyond price by working with stakeholders across the healthcare system to educate audiences around the science and benefits of these therapies. “Communicating the value of any treatment starts well before people reach the negotiating table. Data communications build the evidence for the potential value of a treatment, but it is by showing powerful human stories of daily life with disease— the physical, emotional, and financial burdens – that show the real value that these treatments bring,” says Hare-Scott. After all, what use is scientific progress if patients and societies cannot access the benefits?

Sealey concludes that the only way to truly make CGTs more accessible and affordable is: “to move from the concept of the newest and best technology delivering substantial results, but for only a small customer base and at high costs and with a lot of overhead for the entire ecosystem.” This only makes markets more likely to choose the most efficient option, which inevitably is the non-cell therapy. “For all CGTs to win, our industry needs to go more all-in on building the infrastructure for the future together, proactively. We need to disrupt our very large pharma legacy by asking a really important question: can we collaborate to proactively build a market while aligning our individual solutions next to each other?”

The pricing and access landscape of CGTs is rapidly evolving, and the novel strategies and existing pipeline of therapies is a promise for the future of personalised medicine on the horizon. If the industry can address this vital question of cost through collaboration and communication, we can unlock the benefit and make CGTs a viable option for all.