Kenya is gradually developing into a pharmaceutical hub, but its people are still facing access to medicine challenges. How did the nation’s pharma industry pick up its pace, and what issues are persisting within its healthcare landscape?

Words by Isabel O’Brien

Kenya is famed for its landscape of impressive mountain ranges and spectacular savannahs, yet it is less known as the backdrop to a growing pharmaceutical sector. “Kenya’s pharmaceutical market is already above $1bn,” explains Newton Siele, CEO, Phillips Therapeutics and Pharmaceuticals, Kenya. “This is significant and continued growth is expected over the next 10 years.”

The country is the third largest exporter of pharma products in Africa and the largest exporter in the Common Market for the Eastern and Southern Africa region. Still, due to an uneven distribution of health facilities in the country, 18% of the landmass does not meet the World Health Organization’s criteria for patient access, according to a 2018 study.

As international pharma companies establish an increasing presence in Kenya due to its rapidly growing population, how has it become a ‘pharmerging’ nation with a market value of over $1bn, and what access and other healthcare challenges are affecting the country in tandem?

Early origins

As is the case for many other pharmerging nations, Kenya’s stake in the global pharma market has risen from a flicker to a flame in the last 50 years. While, indeed, a handful of medicines were manufactured in Kenya before it gained independence from British rule in 1963, it wasn’t until it became an independent nation that pharma production picked up momentum on home soil.

The newly-formed Kenyan government was determined to bolster local manufacturing overall in the country, so it implemented a set of economic and trade policies known as import-substituting industrialisation. Working by subsidising local producers and taxing foreign exporters, industrial output quadrupled and the number of industrial establishments more than doubled by 1980.

Kenya’s pharmaceutical market is already above $1bn

However, while these policies encouraged some local pharma innovation – Regal Pharmaceuticals was established in the 1980s and is now one of Kenya’s top pharma companies, as well as a leading manufacturer of pharmaceutical medicines in East and Central Africa – industries such as textiles, foodstuffs and metal products reaped far more rewards.

The big boom

This all changed in the 1990s. A policy specifically benefitting local pharma companies came into force in which healthcare organisations were instructed to ‘buy local’ for things like basic medicine kits where it was advised that 50% should be obtained from local producers. This was followed by the establishment of more key pharma organisations, including Universal Cooperation Limited. Then, the millennium struck, and the pharma sector in Kenya truly started taking shape.

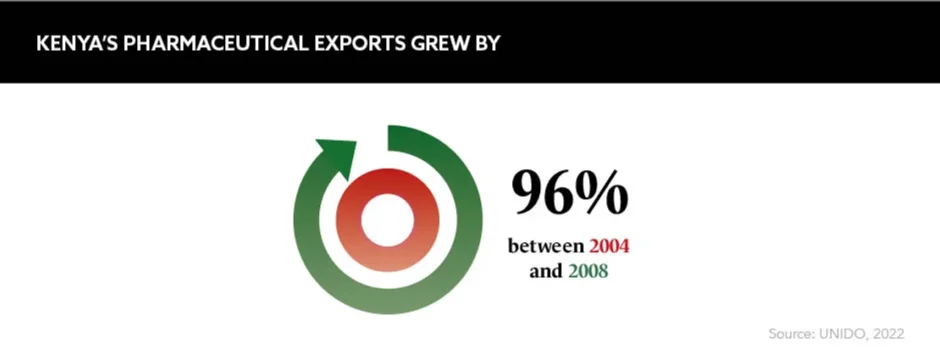

Between 2007 and 2013, the total production of tablets, capsules, liquid preparations for oral use and creams and ointments increased from $34.1m to $154m. Kenya also saw robust growth in its pharmaceutical exports in the new millennium, particularly after 2002. More recently, “the expansion of Kenya’s Pharmacy and Poisons Board from a single office to an entire building was a major step that reflected the expansion of the regulator’s mandate”, according to Lenias Hwenda, Founder and CEO, Medicines for Africa.

She also highlights a recent move by the Kenyan government to “improve Kenya’s economic competitiveness by improving population health”. As a part of its ‘Big Four Agenda’, it plans to keep bolstering its local pharmaceutical sector to achieve healthcare access for all by 2030.

Importing issues

While Kenya is slowly finding a place on the global pharma stage, it has several access to medicine issues that offer a less rosy picture. For example, the nation is not manufacturing nearly enough pharma products to serve its 56 million-strong population. It still imports 70% of its medicines compared to 28% being locally produced – with India serving as its main supplier.

“Medicines are very expensive because of the market dynamics,” explains Hwenda. “And the government does not undertake price controls that you see in European markets like the UK, Germany and Italy to protect patients.” The knock-on impact? Not only are pricing levels unpredictable, but there are heightened risks of supply chain disruption, too.

This was particularly potent during the COVID-19 pandemic when the country faced difficulties securing virus test kits due to inadequate supply networks. This sparked a chain reaction in which Kenyan lorry drivers were unable to pass through borders in Eastern Africa, leading to essential goods shortages and economic downturn.

Health financing fiasco

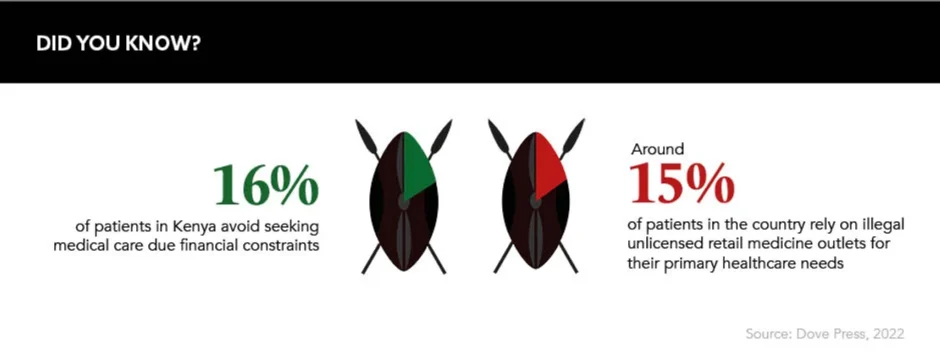

Another key access challenge is the availability and uptake of health insurance in Kenya – estimated to be held by only 19% of the population. While the government supplies free or subsidised access to essential generic medicines for most infectious diseases, as well as those used in reproductive, maternal and child health, other therapies are rarely subsidised or covered by the state.

“Like many sub-Saharan African countries, price is still a significant barrier due to funding challenges,” says Siele. If a local citizen wants to access an advanced therapy they will likely be “out of pocket”, he says, which can cause many to find alternative, and potentially risky, routes to healthcare.

Offering cheaper and more accessible avenues to supposedly legitimate medications, counterfeiters often capitalise on the excess demand. Bad batches of fake medicines have led to many deaths in Kenya, and the country’s south-eastern port Mombasa is a hotbed for the trafficking of fraudulent drugs. Over 12 million units were seized here in 2020.

Non-communicable diseases

According to warnings from global disease surveillance, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are becoming more deadly for people in Africa than infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. This, combined with pricing, supply and insurance issues, could be the next great challenge facing healthcare access and quality of life in Kenya.

“Many people are already living their daily lives with unmanaged NCDs like uncontrolled blood glucose, untreated high blood pressure or undiagnosed cancer,” reflects Hwenda. “This reduces their quality of life and impacts their ability to work and earn money.”

Many people are already living their daily lives with unmanaged NCD conditions

Indeed, diseases such as cancer and diabetes are already accounting for 27% of total deaths and over 50% of total hospital admissions in the country. As a result, the government must prioritise NCDs as a key pillar of their plan to achieve healthcare access for all by 2030 – otherwise not only will health outcomes worsen, but the Kenyan economy could be severely affected, too.

How can pharma help?

Sharing a sadly familiar picture with other pharmerging countries, Kenya’s ascent to pharma power status has not yet solved its access to medicine challenges. So, as international pharma companies move in, they must look holistically at the issues at hand and pursue the most appropriate avenues to help local people.

As Hwenda concludes: “NCD medications, such as those for cancer, cardiovascular medications and immunologicals, are where pharma multinationals can make the biggest impact.” Sanofi, Pfizer and Novo Nordisk have already launched NCD initiatives in Kenya, but other companies must follow suit in order to drive positive change and ensure the country, and its whole population, is supported in the area in which it is increasingly in need.