Interview Summary

Acne vulgaris, commonly known as acne, is a multifactorial, chronic inflammatory skin condition involving the pilosebaceous unit, and is one of the most common skin diseases globally. Acne significantly impacts the quality of life and wellbeing of patients, and can be associated with anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. This skin condition is also associated with substantial healthcare costs and economic burden for society. The treatment of acne is complex and challenging. For this article, EMJ conducted an interview in September 2024 with key opinion leaders Marco Rocha from Federal University of São Paulo, and Brazilian Society of Dermatology, Brazil; Thomas Dirschka from CentroDerm Clinic, Wuppertal, and University of Witten-Herdecke, Germany; and Alison Layton from the Skin Research Centre, Hull York Medical School, University of York, and Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust, UK. The key opinion leaders, who have a wealth of experience and expertise in the clinical management of acne, were asked about the current landscape for the management of acne, and the potential role of the skin microbiome in the development and treatment of this chronic inflammatory skin disease. The experts provided valuable insights into some of the many unmet needs in acne management, particularly the overuse of antibiotics and the lack of effective alternative therapies for this condition. The experts discussed the contribution of the skin microbiome and the potential role of microbial imbalances in the development of acne, and the potential of prebiotics and probiotics in restoring skin health. The concept of integrating microbiome-modulating strategies into conventional acne treatment, and whether there is a connection between the skin microbiome and psychological conditions such as depression, were also considered. A further topic covered was educating patients and parents about acne. Finally, the experts outlined what the future landscape of acne management might look like.INTRODUCTION

Acne vulgaris, commonly known as acne, is a multifactorial,1 chronic inflammatory skin condition involving the pilosebaceous unit,2 a structure comprising the hair follicle, hair shaft, and sebaceous gland.3 Acne is one of the most common skin diseases globally,4 affecting more than 80% of adolescents and young adults,5 many of whom develop acne scars.6 This skin disease significantly impacts the quality of life and wellbeing of patients,7-11 and can be associated with anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.11 Individuals with acne can feel embarrassed by their lesions or post-acne marks, and often feel stigmatised.12 Acne is also associated with substantial healthcare costs and economic burden for society.13

Layton explained that knowledge of the pathophysiology of acne has unfolded significantly over the last 5 years, and understanding of this condition at a molecular level has improved; however, there remain many unanswered scientific questions in this area. There are few studies to help guide decisions for the long-term management of acne. The treatment of acne is complex and challenging.2

THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE FOR ACNE MANAGEMENT

Overuse of Antibiotics in Acne Management and Limited Treatments to Reduce Sebum

Layton highlighted that one very important unmet need from a clinical perspective relates to the overuse of antibiotics for the treatment of acne,14,15 and the resulting concern about antimicrobial resistance,14,16-19 in the context of a lack of effective alternative therapies for this condition. Harbouring resistant Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes; formerly Propionibacterium acnes) in patients with acne treated with antibiotics has been shown to correlate with poor clinical response,20 but this depends on the balance of resistance present within the individual pilosebaceous follicles. As antibiotics work through antimicrobial as well as anti-inflammatory mechanisms, the presence of antimicrobial resistance does not necessarily impact on acne response; however, the negative impact and consequences of antimicrobial resistance may be much broader than just in the skin.

Notably, there is variation between the current guidelines on the classification of acne severity, indications for initiating treatment with oral antibiotics, and maximum duration of oral antibiotic treatment; however, there is agreement that the non-antibiotic topical treatment benzoyl peroxide should be co-prescribed when administering antibiotics, and antibiotics should be used as part of a combination regimen.21

Layton confirmed that acne is a disease of sebogenesis, and that both the regulation of sebum excretion and the composition of sebum are integral to the pathogenesis of acne. Therapies that target sebum, an oily substance produced by the sebaceous gland that forms a hydrophobic protective barrier on the skin,22 are needed to regulate sebum secretion3 and alterations in sebum composition.23 There are limited systemic treatments available for acne that effectively reduce sebum, including hormonal therapies for females (such as combined oral contraceptives, and spironolactone24), and isotretinoin for males and females.25

Up until very recently there were no topical agents that reduce sebum; however, clascoterone, a novel topical anti-androgen that is approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne in both male and female patients,26,27 has been shown to reduce sebum to some degree.28

Layton emphasised: “We need alternatives to antibiotics for the treatment of acne, I don’t think there is any question about that. Also, there are no topical therapies available that significantly reduce sebum. These remain key unmet clinical needs in the management of patients with acne.”

Further Unmet Need in Acne Treatments

When necessary, female patients may benefit from systemic treatment with off-label use of anti-androgen drugs, such as spironolactone.29 Rocha pointed out that studies are needed in adult females with acne to understand the safety and efficacy of bicalutamide, a second-generation, oral, non-steroidal anti-androgen with a similar structure to the first-generation, oral, non-steroidal, anti-androgen flutamide.30,31 Rocha suggested that: “If additional studies are conducted to show the safety and efficacy of bicalutamide, in the future we may see different options to treat adult female acne without using oral antibiotics.”

In terms of the ‘journey’ of acne, Layton stated that there is agreement and some evidence for the use of maintenance therapy,21 but there is a lack of evidence for effective preventative therapies for acne. Layton suggested that novel therapies for the early stages of acne development, to prevent progression to a more aggressive form of the skin disease, is also an area of unmet need that requires research effort.

A further unmet need highlighted by Layton is identifying and providing the sort of treatments that patients want to use. Topical therapies are not always tolerated well by patients because they can lead to adverse effects as a result of increased transepidermal water loss and impaired skin barrier integrity. Dirschka agreed that most conventional acne treatments, including topical benzoyl peroxide and vitamin A preparations, are irritative,32 which can hinder treatment, particularly in individuals with sensitive skin. Therefore, improving formulations is a further unmet need in acne treatment.

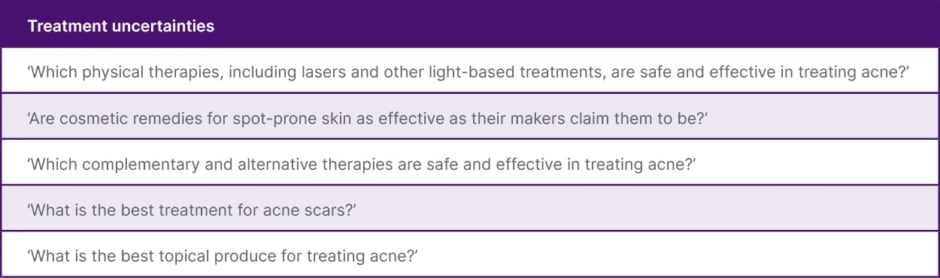

Layton described a James Lind Alliance Acne Priority Setting Partnership,33 the process of which identifies and ranks treatment uncertainties through a collaboration between many stakeholders with a vested interest in acne, including people with acne and their relatives, allied health professionals, and regulators.33 This established National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) process provides a platform to help distinguish ‘what we don’t know’, and ‘what we might want to know’, and identifies the most common treatment uncertainties; hence defining potential areas for future research. The most common uncertainties identified by participants in this study are shown in Table 1.33

Table 1: The most common treatment uncertainties identified by participants in the James Lind Alliance Acne Priority Setting Partnership.33

Dirschka outlined that patients with acne often try home remedies,34,35 or over-the-counter treatments,35 consult pharmacists, and search the internet before visiting a general practitioner or dermatologist. Layton concurred that patients often try to resolve their acne symptoms themselves before visiting a doctor, and the treatments they use are often numerous, expensive, and ineffective.

Unmet Need in Managing Truncal Acne

Other clinical unmet need includes ascertaining whether truncal acne36 has the same pathophysiology as facial acne, and can be managed in a similar way. This is particularly important as truncal acne has been shown to greatly impact quality of life,37,38 but is often overlooked in clinical practice.36,39-41

Unmet Need in Managing Acne Sequelae

Acne-related scarring is common, and can even occur in patients whose acne is effectively managed.42 The psychosocial impact of post-acne scarring is substantial.7 Current treatments for scarring in patients with acne often involve invasive procedures.43 According to Layton, there is some evidence to suggest a susceptibility to scarring in patients with acne, as these patients mount a different innate immune response,43 and there is often a family history of acne-induced scarring.44,45 Further research effort is needed to define which patients with this chronic inflammatory disease are likely to scar.

A further challenge specified by Rocha is how to prevent post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), which is a major cosmetic concern, particularly in individuals with darker skin complexions.46,47 PIH is often perceived by patients as more distressing than the acne itself,48 and individuals with PIH are stigmatised.49

Unmet Need in Specific Patient Populations with Acne

Rocha highlighted that there are unmet acne treatment needs for specific populations, such as pregnant females,50 and transgender males.51

Several commonly prescribed acne therapies are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation, and there is a paucity of guidelines to direct management of acne in females who are pregnant or breastfeeding.50

Acne is a common adverse effect among transgender males receiving testosterone.51 Rocha noted that discontinuation of isotretinoin treatment in this population is associated with high rates of flare-ups and recurrence, as well as poor outcomes.52 Furthermore, there is limited scientific literature on the issues arising from hormone therapies in this population in the short- and long-term, as well as a lack of robust clinical studies to guide treatment of these individuals.2,53 There are several barriers to acne treatments in transgender males, including cost, absence of multidisciplinary care, mistrust of the healthcare system, and a dearth of education about transgender-specific acne care.54

Disparity in Access to Acne Treatments

In Germany, more than two-thirds of acne treatments can be purchased over-the-counter, according to Dirschka. In contrast, Layton highlighted that, although benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter in the UK, most treatments are only available on prescription.

The experts suggested that isotretinoin may be the most effective drug currently available for acne, as it impacts on the main pathophysiological factors of acne. Dirschka described a disparity in the availability of the acne treatment, isotretinoin. Some Asian countries have easy access to this therapy, which is in contrast to the UK, where isotretinoin is only licensed for severe acne that has not responded to combinations of topical and oral agents. Furthermore, a recent regulatory review in the UK recommends that patients under 18 years require confirmation from two prescribers that the medication is warranted.55

THE POTENTIAL ROLE OF MICROBIAL IMBALANCES IN ACNE DEVELOPMENT

The skin microbiome is composed of various microorganisms and protects the body against pathogens, trains the immune system, and facilitates the breakdown of organic matter.56 Dysbiosis (an imbalance of microorganisms) in the skin microbiome has been implicated in the development of acne.56

C. acnes is important in the maintenance of healthy skin, but can also act as an opportunistic pathogen in acne.57 However, the quantity of C. acnes does not appear to trigger acne,57,58 as patients with acne do not have higher levels of C. acnes in follicles than individuals without this skin disease.57

Rocha clarified that there is a loss of bacterial diversity in the skin microbiome in acne compared with healthy skin. Specifically, a loss of balance between the different C. acnes phylotypes, and a simultaneous dysbiosis of the skin microbiome, is associated with acne.58 The loss of diversity of C. acnes phylotypes triggers activation of the innate immune system,59 which leads to cutaneous inflammation.

Other bacterial species important in the skin microbiome include Staphylococcus epidermidis (S. epidermidis) and Cutibacterium granulosum (C. granulosum; formally Propionibacterium granulosum).60 C. acnes and S. epidermidis are commensal bacteria that have been described as ‘skin microbiota sentinels’ with a key role in the skin ecosystem, preventing microbiota disequilibrium by competing with pathogens and producing beneficial bacterial metabolites.61 The interplay between C. acnes and bacteria such as S. epidermidis is integral for skin health.60 C. granulosum is found in sebum-rich areas but at much lower levels than C. acnes.60 This commensal bacterium rarely causes infections and is generally considered non-pathogenic.62

Rocha emphasised: “The balance in the skin microbiome has two sides, like a coin – microbial balance and microbial imbalance (dysbiosis) – and we have to understand both sides of the coin.” Rocha explained that on one side, the bacterial diversity of the skin microbiome maintains healthy skin. On the other side, the dysbiosis of the skin microbiome can activate the immune system, causing the release of cytokines and initiation of inflammatory processes. Rocha added that understanding the skin microbiome provides a potential opportunity to prevent the development of acne.

Layton concurred that the difference between the acne microbiome and a healthy skin microbiome is well known,63,64 and there is interesting ongoing research to investigate the microbiome and explore the “science behind acne”; however, there is a lot that is still unknown about the skin microbiome. Layton disclosed that it is not yet known whether manipulating the microbiome to increase bacterial diversity to more closely resemble that of healthy skin impacts the development and progression of acne. In addition, Layton noted that there is no good model of the pilosebaceous unit and such a model would be helpful.

Dirschka pointed out that it is unknown why different individual hair follicles on the face respond differently (i.e., with inflammation versus without) in a patient with acne. According to Dirschka, as most of the hair follicles adjacent to the acne lesions are unaffected, even though they presumably have the same bacterial colonisation, there must be specific differences in the regulation of individual hair follicles. Dirschka stated: “We do not know why inflammation is triggered in some individual hair follicles and not in others. Clearly, not all follicles are alike. If we knew the reason behind these differences, it could be a very good clue to understanding acne.”

Dirschka believed that there is a misconception that the first step in acne pathogenesis is keratinisation disorder at the acro-infundibulum of the hair follicle,65 and that bacteria play a role later, after sebum has accumulated in the acro-infundibulum. Dirschka emphasised that this misconception underpins most of the current treatment guidelines, and that the guidelines need to be updated in the context of new information about the skin microbiome and the early stages of acne development.

THE POTENTIAL OF PREBIOTICS AND PROBIOTICS IN RESTORING SKIN HEALTH

Rocha specified that there are numerous dermocosmetic products for acne that include prebiotics as they are easy to incorporate; however, these products have limited effectiveness.

According to Rocha, an important consideration in the development of probiotic creams, gels, or lotions (i.e., including live bacteria) for acne is the use of preservatives and other chemical constituents in these products that might kill the ‘good bacteria’ in the skin. The challenge is to create a product that effectively modulates the immune cells and the inflammatory processes, competes with pathologic bacteria, and does not affect the ‘good bacteria’ in the skin.

Rocha noted that most of the information available about the use of probiotics to manipulate the skin microbiome and treat acne is derived from basic scientific research rather than clinical studies, and currently there are no products on the market in this category. Rocha specified that the use of probiotics in the treatment of acne is currently hypothetical.

Probiotics in the treatment of acne are an area of great research interest,66 but there are limited studies on ClinicalTrials.gov (12 studies, as of September 2024: six of which are completed [no results reported], two are completed with results, two are active, and two have unknown status), and few published studies. Some examples of the published studies are discussed as follows.

Enterococcus faecalis is a widely used probiotic that has shown benefits for acne treatment through antimicrobial activity against C. acnes.67 CBT SL-5, an antimicrobial peptide from E. faecalis SL5,68 was shown to be a feasible and well-tolerated option for improving acne severity and skin microbiome dysbiosis in patients with mild-to-moderate acne in a randomised, placebo-controlled, split-face comparative study.67

A prospective, randomised, open-label study comparing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of an acne treatment regimen comprising either probiotic supplementation or minocycline or both therapies in patients with mild-to-moderate acne showed significant improvement (p<0.001) in total lesion count 4 weeks after treatment initiation in all patients, with continued improvement seen with each subsequent follow-up visit.69 The study authors reported that probiotics are a therapeutic option or adjunct for acne vulgaris as they provide a synergistic anti-inflammatory effect with systemic antibiotics.69

In another study, an extract of Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum-GMNL6) applied to the faces of study volunteers was shown to reduce melanin synthesis, formation of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm, and the proliferation of C. acnes, and improve skin moisture, skin colour, spots, wrinkles, ultraviolet spots, and porphyrins.70

Probiotic-derived lotion containing Lactobacillus paracasei MSMC 39-1 was shown in a randomised controlled trial to be safe and effective for treating mild-to-moderate acne, with the outcome comparable to that with 2.5% benzoyl peroxide.71

In addition, a capsule composed of the probiotic Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus and the cyanobacterium Arthrospira platensis was associated with improvement in acne symptoms (severity, total number of lesions, number of non-inflammatory lesions) in a 12-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical study.72

Rocha considered that further clinical studies are needed using these novel treatments (including treatment combinations) in different patient populations with varying severity of acne.

INTEGRATING MICROBIOME-MODULATING STRATEGIES INTO CONVENTIONAL ACNE TREATMENT

According to Dirschka, it is not yet possible to define how emerging research on the skin microbiome aligns or integrates with current best practices and conventional approaches in acne management: “We are entering a completely new field that is not in line with our conventional concepts of acne. We have to figure out where and how to position these new treatment options that we will have in the future. This is not an ‘add-on’; this might be a new field, a new therapeutic era.” Dirschka emphasised that the exact function of the bacteria and the precise positioning of the microbiome in the pathogenesis of acne are unknown. Therefore, it is also not yet possible to anticipate the challenges that might be associated with integrating skin microbiome-modulating products into standard acne treatment protocols, and how these might be overcome.

Dirschka clarified that further research is needed into the “new pathogenic concept of acne that integrates the microbiome”, and knowledge of how acne is triggered and the inflammatory process is set into action will bring new understanding of treatment. However, skin microbiome-modulating products that are well tolerated with minimal systemic side effects might be applicable to mass markets, rather than just for individual patients. Dirschka summarised that these products could have an important role in the management of patients with any type of acne in the future, potentially being placed as fundamental acne treatments, provided dysbiosis of the follicle is confirmed as an important pathogenic factor in the development of this skin disease. Rocha highlighted: “We are still looking for a target in acne – when we have a good target, we can create effective biologics to integrate into conventional acne treatment strategies.”

Layton described modifying the skin microbiome in acne as a complex area of research that is being explored, and proposed that using transcriptomics73-76 to reveal the chronological order of acne is an innovative approach that could aid understanding of the pathogenesis of acne at a cellular level, thereby leading to improved research and treatment strategies. Layton expressed interest in research comprising clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology,77 with a view to using this to modify the skin microbiome in skin disease.78 However, Layton noted that removing the more virulent C. acnes strains may have the potential to trigger an acute inflammatory process, which could cause a myriad of problems for patients.

Rocha commented that it is not yet known whether oral probiotics can interact with oral antibiotics and improve outcomes, or whether this will reduce efficacy in modulating inflammatory processes. Furthermore, Rocha highlighted the potential interactions between topical acne treatments with microbiome-modulating tools, such as probiotics, and explained that new treatments have to be integrated carefully into acne management. For example, the use of benzoyl peroxide with microbiome-modulating dermocosmetics would be complicated if benzoyl peroxide kills the microbiome probiotic. In this case, it may be necessary to use the treatments separately (e.g., microbiome-modulating treatment in the morning and benzoyl peroxide in the evening). Rocha noted that there are many unanswered questions surrounding topical and systemic approaches in acne management.

IS THERE A CONNECTION BETWEEN THE SKIN MICROBIOME AND PSYCHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS?

The experts remarked that there is no strong evidence to indicate that the skin microbiome influences brain cognitive function and psychological conditions; however, this is an area of research interest. For example, Wang et al.79 suggested that there was a possible relationship between the skin microbiome and brain cognitive function in a pilot study. In addition, Wingfield et al.80 reported a potential connection between the microbiome in the oral mucosa and depression in a survey-based study. Deterioration of lesions in psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin disease with systemic manifestation, is associated with increased production of inflammatory mediators, which might impact neurotransmitter levels, and could lead to the development of depression81,82 and anxiety.81

However, Layton clarified that for acne specifically, it is not known whether there is a connection between the skin microbiome and brain cognitive function and psychological conditions.

Rocha discussed that there is evidence of a connection between gut dysbiosis and the development of psychological conditions, such as anxiety and depression,83,84 but this is not completely understood. In addition, gut dysbiosis has been shown to influence the skin in some, but not all, patients, and the reasons behind this disparity are unclear.85,86 Rocha described that there is limited understanding of the way in which the pathways in the gastrointestinal system, the skin, and the brain work together, and research into the gut–skin–brain axis is an open field that requires attention.

According to Rocha, it is essential to study the gastrointestinal system, the skin and the brain together, rather than individually, to help understand the connection between the different systems: “Enhancing our understanding of the gut–skin–brain axis will help us to understand more about human science, and enable us to develop our treatment approaches and clinical practices in the future.”

EDUCATING PATIENTS AND PARENTS ABOUT ACNE

Layton described the level of knowledge and understanding of acne among patients and parents as poor, and parents are particularly concerned about the use of antibiotics for the treatment of this skin disease.87

According to Dirschka, the impact of the internet is considerable in this typically young patient population, and they are particularly susceptible to misinformation, considering their impressionable age, concern about their appearance, and easy access to social media platforms and other online resources.88 A study to assess the awareness levels amongst young people indicates that there are several misconceptions and a gross lack of knowledge about acne that need to be addressed.89

Although there are many online resources providing information on acne, there are numerous myths and considerable misinformation spread about this dermatological condition.90-92 Layton proposed that educational programmes are needed to dispel the myths and combat the misinformation surrounding acne, and to inform patients and parents about how acne develops, as well as the potential positioning of treatments that modulate the skin microbiome. Layton acknowledged that the pathogenesis of acne and the skin microbiome are complex concepts; therefore, clinicians should build a narrative to describe the development and treatment of acne using simple language and schematics that resonate with patients and parents. Importantly, Rocha noted that “acne is related to bacteria but is not an infectious disease”, and this fact could be a starting point for educating patients about acne.

The experts suggested that clear and basic descriptions of the mechanism of action and effectiveness of treatments could be used to encourage patients to adhere to treatment protocols, thereby improving compliance. Furthermore, patient education to set expectations and providing strategies to minimise irritation associated with acne treatments could help to optimise treatment outcomes.93 Succinct and straightforward information on skin microbiome-modulating treatments (once sufficient evidence of the efficacy and safety of these therapies is accrued), and their potential use in combination treatments, underpinned by the aim to use fewer antibiotics, could provide a platform for healthcare professionals to motivate patients to consider new treatment options.

Layton referred to a NIHR-funded programme, which is developing an online tool called Acne Care Online94 for use in the community to educate patients about when and how to acquire treatments, how to use the treatments, and how they work.

The experts agreed that the quality of education of patients and their families about acne needs to improve through effective communication strategies to ensure that healthcare messages reach the target audience. Layton pointed out that adolescent patients are heavily influenced by health messaging on social media, and platforms such as TikTok are a vital tool to reach younger generations. Dirschka remarked that influencers on TikTok appear to have a greater impact on some members of the acne community than doctors and dermatologists, and this is an area requiring attention.

FUTURE LANDSCAPE OF ACNE MANAGEMENT

Layton outlined the importance of widespread adoption of a patient-centred approach95 in the management of acne to optimise outcomes in the context of the varying presentation, chronicity, and impact on health-related quality of life of this common skin disease. Furthermore, Layton emphasised the need for increased support in acne research: “Unfortunately, acne is the ‘poor cousin’ compared with other inflammatory skin conditions, such as psoriasis and eczema, when it comes to funding, despite the fact it has such a profound negative impact on our adolescent population at a time when they are undergoing significant physical and emotional transition. We need to medicalise acne as a disease with dermatological, psychological, and potential systemic impact, and we need to do more to address this common problem.”

According to Dirschka, a key goal for the future is that new treatments for acne are well tolerated, effective, with a “robust pathogenic concept” behind the treatment, and perhaps available over the counter. Furthermore, Dirschka commented: “Most of our patients are teenagers and young adults who want to see rapid improvement in their acne, but this is impossible. Acne treatment is a marathon… We have to find good ways to communicate with this young patient population in the future.”

Effective communication and patient education are indeed essential, as managing expectations and ensuring adherence to long-term treatment plans can significantly impact outcomes.

However, alongside the evolving therapeutic approaches, it is equally important to explore how emerging scientific research, particularly on the skin microbiome, may shape the future of acne treatment.

Rocha summarised that research in probiotics is in the early stages, and there are many challenges to resolve before the efficacy of these products in acne can be completely understood. Rocha stated: “This is an open field, and we do not know how new treatments will work in relation to conventional acne treatments. I am very hopeful that probiotics will become an effective new treatment for our patients. Research in this area is vital in the drive to reduce the use of antibiotics among patients with acne.”