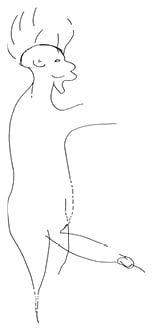

Although human depictions are scarce in prehistory, i.e. preceding our first records of written language, both male and female genital representations are relatively common motives; they are depicted at prehistoric times all over the world on cave walls, rock shelters, and pieces derived from excavations of archaeological sites of stone, bone, and antler portable material and decoration. The most common representations date from the Upper Palaeolithic period (approximately 40,000–12,000 years before present [BP]) and appear more numerous in Western Europe, especially Iberia and France. These graphical elements suggest that early modern humans (Homo sapiens) had an awareness of the physiological phenomena (erection, copulation, ejaculation, and orgasm) related to sexuality and reproduction (Figure 1), and of the related pathological processes (phimosis, paraphimosis, urethral discharge, and genital mass). Indirect evidence exists that suggests foreskin retraction and/or circumcision was also performed, and a detailed analysis suggests that other penile decoration rituals (tattooing, piercing, and scarification) were performed. These were possibly done as group recognition strategies, mainly during the Upper Magdalenian period (11,000–12,700 years BP), representing one of the oldest known anthropological registries of body decoration. Circumcised and decorated phalli currently constitute the earliest records of human anatomical instrumentation and thus imply the existence of surgical knowledge during the late prehistoric period.

Figure 1: Ejaculating human represented in the open air site of Ribera do Piscos (Vilanova de Foz Côa, Portugal). A large size male figure reveals seminal emission and male orgasm with open mouth and lines coming out from his head.

Human and animal erection captivated the artists’ minds and possibly implied virility and strength, opposed not to the feminine, but to nature itself.

Many ithyphallic men were depicted as partly animal and partly human. In several instances, male erection was associated with serious danger or death, and could be interpreted as part of a shamanistic representation linked to the loss of the soul. Many portable art elements are made of antler or bone and have the form and size of the penis. Although their specific use is unknown, it is clear that they were precious elements because the materials could instead have been used to produce spear points, pendants, or even needles. The complementation between male and female genitalia is also a constant, and was sometimes explicitly represented in the form of a human or animal coital scene (Figure 2). The positions are varied and, although infrequent, may represent a ‘Kamasutra-like’ guide. Mating was rarely linked to childbearing representation, which implies knowledge of contraceptive practice. In a curious post-Palaeolithic carving in an open-air site in the Côa Valley, Portugal, a condom-like object is represented. In Neolithic Europe (9,000 years BP), the penis was often evident on male figures depicted on rock shelters but with less anatomical detail than in naturalistic Palaeolithic art.

Figure 2: Coital scene represented in Cueva de Los Casares (Riba de Saelices, Spain). A human couple facing each other and the male figure displays an enormous penis placed on the pubis of the female figure.

Agriculture led to male dominance and female genitals were less frequently depicted. The penis is recognised in stone sculptures of possible ritual use, like the phallic collection in the Gozo Museum of Archaeology, Malta. Evidence from the Copper age (5,500 years BP) implies a widespread monumental use of the penis form in numerous menhirs all over the Atlantic shore, and in schematic shelter wall art in the mountainous landscape of Southern Europe; these symbolic human figures often have a prominent penis. Penile representation in fine carving during the late Bronze-Iron age (3,000–2,500 years BP) suggests penile infibulation. This form of penile mutilation prevented warriors from losing their energy in penetration and has been performed in many tribes of modern primitives. In conclusion, penis depiction during prehistory has constantly evolved and many clues can be obtained in the absence of written language when attention is paid to this source of knowledge.