Abstract

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and seronegative elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis (SEORA) are two of the most frequent inflammatory rheumatologic diseases in elderly patients. At first presentation, there are many similarities between PMR and SEORA, that may lead to a real diagnostic conundrum. The most relevant similarities and differences between PMR and SEORA are discussed in this review. In addition to the acute involvement of the shoulder joints, important features characterising both diseases are morning stiffness longer than 45 minutes, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a good response to low doses of prednisone. Some findings (such as erosive arthritis or symmetrical involvement of metacarpophalangeal and/or proximal interphalangeal joints) can help to make the diagnosis of SEORA, whereas shoulder and hip ultrasonography and 18-FDG PET/CT seem to be less specific. However, in several patients only long-term follow-ups confirm the initial diagnosis. A definite diagnosis of PMR or SEORA has significant therapeutic implications, since patients with PMR should be treated with long-term glucocorticoids, and sometimes throughout life, which predisposes the patients to serious side effects. On the contrary, in patients with SEORA, short-term treatment with glucocorticoids should be considered when initiating or changing disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, followed by rapid tapering.

INTRODUCTION

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is considered the most frequent inflammatory rheumatic disease in the elderly.1,2 Its highest prevalence is between 70–80 years of age, with a slow increase until the age of 90 years.3 Classic symptoms are bilateral pain and aching and stiffness in the shoulders and pelvic girdle, associated with morning stiffness lasting >45 minutes. In some patients, an inflammatory pain in the neck is also present.4,5 Inflammatory markers (such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein concentrations) are usually raised. However, normal ESR and C-reactive protein concentrations should not be a reason to exclude PMR.6-8

Elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis (EORA) is, by definition, a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) developing in persons >60 years of age.9,10 Recent studies have confirmed that RA is among the most common inflammatory disease in older age groups, with a 2% prevalence.11 When rheumatoid factor (RF) and anticitrullinated peptide/protein antibodies (ACPA) are absent, seronegative EORA (SEORA) is diagnosed. In some patients, a clinical onset that mimics PMR is possible.12-14

SEORA can be considered the most frequent PMR mimicking-disease. In some studies, >20% of patients changed the first diagnosis of PMR to SEORA during follow-ups.15-17 In 1992, Healey18 suggested that PMR and SEORA might be the same entity. Recently, this point of view has been put forward again.19

In this review, the authors discuss the diagnostic and classification criteria of these two inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Furthermore, the authors highlight the main differences and similarities between seronegative and seropositive RA, EORA, and young-onset RA (YORA), and EORA and PMR-like EORA. Finally, the authors discuss therapeutic differences and similarities: both steroid and non-steroid therapeutic options are discussed.

DIAGNOSTIC AND CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA

The diagnosis of PMR is challenging, due to lack of any specific diagnostic test and the presence of other conditions mimicking PMR, mainly elderly onset seronegative RA.20-22 Due to uncertainty related to the diagnosis of PMR, a prompt response to glucocorticoid (GC) treatment has been commonly used to establish the diagnosis. However, only about half of patients respond completely to GC after 3 weeks of treatment with 15 mg oral prednisolone.23 Additionally, response to GC can be observed in other mimics of PMR.24

To date, several diagnostic and classification criteria sets for PMR have been defined in the literature; they have some features in common, such as an age cut off, elevated markers of inflammation, and pain and/or stiffness in the shoulder and/or hip girdles.1,25-28

To improve the criteria specificity for PMR, the 2012 provisional European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)/American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for PMR used, for the first time, findings of shoulder (subdeltoid bursitis, biceps tenosynovitis, and/or glenohumeral synovitis) and hip (synovitis and/or trochanteric bursitis) ultrasound (US) along with clinical presentations.28 In this regard, the absence of positive RA serology (RF and ACPA)and peripheral synovitis is in favour of diagnosis of PMR and aims to distinguish PMR from RA. Although autoantibodies such as RF and ACPA are mostly seen in RA, diagnostically insignificant low levels of RF can be detected in elderly people.29 It is worth noting that these classification criteria are designed to discriminate patients with PMR from other mimics of PMR and are not meant for diagnostic purposes.

In a single-centre study, Macchioni et al.30 compared the performance of 2012 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for PMR with prior criteria sets in new-onset, confirmed PMR patients using ultrasonography findings. They found that the EULAR/ACR classification criteria had the highest ability to discriminate PMR from RA and other inflammatory articular diseases.30 However, in a study by Ozen et al.31 comparing the performance of different criteria sets in patients >50 years of age, presenting with new-onset bilateral shoulder pain with elevated acute phase reactants who fulfilled the EULAR/ACR classification criteria, the sensitivity of the EULAR/ACR classification criteria for PMR was high but its ability to discriminate PMR from other inflammatory/noninflammatory shoulder conditions, especially from seronegative RA, was suboptimal.31

The 1987 ACR32 and, more recently, the 2010 ACR/EULAR33 classification criteria for RA provide criteria for the classification of patients as having RA as opposed to other joint diseases. The specificity and sensitivity of the old criteria was not adequate for the classification of patients with early inflammatory arthritis as having RA.34 To detect early RA, on the other hand, the new criteria give much weight to RA serologic biomarkers, which may result in failure to identify individuals with seronegative RA.35 Thus, the difference between proportions of patients fulfilling the new or old criteria sets highlights the importance of both criteria, especially in cases of seronegative RA.

SEROPOSITIVE VERSUS SERONEGATIVE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Based on the status of RA serology (i.e., RF and ACPA), RA can be categorised into seronegative RA and seropositive RA. This classification is valuable for diagnosis, making the treatment decision, and predicting the prognosis of RA, where the presence of RF and ACPA have been regarded as poor prognostic factors.35-37 In comparison with seropositive RA, seronegative RA has been considered a less severe disease with less radiographic damage progression.38-42 Less intensive treatment has been suggested in previous literature, but the necessity of changing to another conventional synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) was underlined by the 2016 update of the EULAR treatment recommendations, also applying to patients with seronegative RA when they do not achieve the treatment target.36

Findings in recent literature in respect to the influence of seronegative status on clinical course and treatment are controversial. In a recent study by Nordberg et al.,43 wherein 234 patients with RA (15.4% seronegative) who fulfilled the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria were recruited between 2010 and 2013, the authors found that ultrasonography scores for joints and tendons, number of swollen joints, disease activity score, and Physician’s Global Assessment were significantly higher in seronegative patients compared with seropositive patients, representing a higher level of inflammation in seronegative RA patients.43 These findings may pinpoint the need for a high number of involved joints for seronegative patients to fulfil the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA.44,45 Furthermore, after a 2 year follow-up, the authors found similar disease activity measures, radiographic progression, and remission rates, but a slower treatment response in seronegative RA, despite higher levels of inflammation in seronegative RA at baseline.43 In contrast, seropositive RA has been suggested by other authors to represent a more aggressive subset of disease with significant radiological joint damage, which needs to be treated more intensively.46-49

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN EARLY-ONSET AND YOUNG-ONSET RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

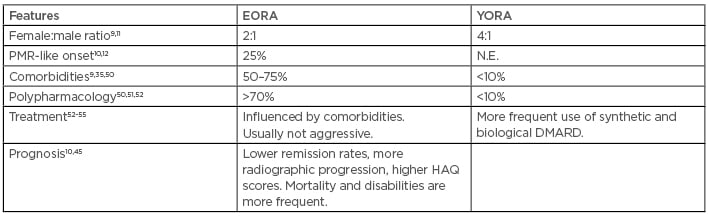

Similar to other diseases, RA has some significant differences in different age group populations. The main differences between EORA and YORA have been summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Main differences between elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis and young-onset rheumatoid arthritis.

DMARD: disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; EORA: elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; N.E.: not evaluated; PMR: polymyalgia rheumatica; YORA: young-onset rheumatoid arthritis.

For example, there is a PMR-like EORA, a clinical feature that can occur in 25% of cases.10 On the contrary, PMR-like YORA is very exceptional. Indeed, YORA is classically a symmetric polyarthritis involving the small articulations of hands, wrists, and/or feet, without involvement of shoulders.12,13

The effect of age on RF positivity is well known: in older persons, it can be expression of an age-related dysregulation of the immune system, with no diagnostic significance.56 As already highlighted, recent studies showed that seronegative RA is not a mild form of the disease, requiring intensive treat-to-target therapy similar to treatment of seropositive RA, it can have more inflammatory activity compared to patients with seropositive RA, and it can result in a worse prognosis regardless of age.43,45

Comorbidities are commonplace in patients with EORA,51 and their interference has to be properly assessed.52 Moreover, in elderly patients, polypharmacology and an age-related impairment of organ functions can favour drug side effects more than in the younger patient or when using a less aggressive treatment.53,54

Early-onset Rheumatoid Arthritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica-Like Early-onset Rheumatoid Arthritis: Clinical and Instrumental Differences and Similarities

EORA is considered the most enigmatic PMR-mimicking disease. In addition to the acute involvement of the shoulder joints, characteristic features of both diseases are morning stiffness for >45 minutes, raised ESR, and a good response to low doses of prednisone. In clinical practice, even if physicians should look for diagnoses other than pure PMR when a steroid treatment with prednisolone 12.5–25.0 mg per day does not result in significant improvement,20 the possibility that the PMR patient can have a favourable response using a GC different from prednisone or prednisolone should be taken into account.12

Constitutional manifestations such as fever, loss of appetite, weight loss, and malaise can be present both in EORA and in PMR.15 On the other hand, patients with PMR may show distal synovitis, presenting as monoarthritis or an asymmetrical oligoarthritis involving mainly wrists and knees. In PMR, synovitis is usually transient and mild, non-erosive, and will be resolved completely after initiation of corticosteroid treatment or increasing the prednisone dose.15,16,57,58

In contrast to EORA, most relapses present as a monoarthritis. When arthritis in the wrist is associated with at least one metacarpophalangeal or proximal interphalangeal joint at disease onset, the probability of PMR diagnosis is minimal. This was calculated to be 4.8% in a 5-year prospective study.59 Diffuse swelling of the distal extremities with pitting oedema and carpal tunnel syndrome can be present both in patients with PMR and in patients with EORA.60,61 In particular, remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting oedema, characterised by symmetrical distal synovitis, pitting oedema of the dorsum of the hands, elevated acute phase reactants, seronegativity of RF, and rapid response to low-dose steroids is a frequent finding in patients with PMR.60,62

The clinical utility of ACPA in the differential diagnosis of EORA and PMR has been highlighted, and their presence in a patient with clinical symptoms of PMR must be interpreted as highly suggestive of EORA.63 On the other hand, as already underlined, the presence of RF should not be an exclusion factor for PMR, since RF can be detected in approximately 10% of the healthy population aged >60 years.

Shoulder and hip US examinations can give important contributions as proposed by EULAR/ACR classification criteria. However, their usefulness is counterbalanced by the absence of pathognomonic findings.64,65 As highlighted by the EULAR/ACR collaborative group, patients with PMR were more likely to have abnormal US findings in the shoulder (particularly subdeltoid bursitis and biceps tenosynovitis), and somewhat more likely to have abnormal findings in the hips (particularly trochanteric bursitis or synovitis) than comparison subjects as a group. However, PMR could not be distinguished from RA on the basis of US, but instead from non-RA shoulder conditions and subjects without shoulder conditions.28

Differentiation between PMR and EORA using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT has also been proposed.66 However, differences in the numbers of area considered by the investigators, the lack of standardisation for the technique, and the limited access to PET in the clinical practice, are critical points to consider.67

The possibility that both PMR and SEORA can be present in one patient19 is a further confirmation of great diagnostic difficulty.

Early-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica: Pathophysiological Similarities and Differences

Some considerations about pathogenesis of these two diseases can be useful. The possibility that SEORA and PMR can have similar patterns of human leukocyte antigen association has been highlighted in population studies.68 However, the association between human leukocyte antigen-DRB1 genotypes and susceptibility to PMR and SEORA is still controversial.69 Toll-like receptors (TLR) play an important role in the activation and regulation of the innate and acquired immune response, through recognition of pathogen-related molecular patterns and endogenous peptides. TLR are expressed on many cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells, and are highly present in RA synovium as well as in peripheral mononuclear blood cells in patients with active PMR. Coding variants in the TLR4 gene have been often associated with inflammatory and infectious diseases, but when two of these polymorphisms (Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile, capable of altering the function of the receptor) were studied in patients with PMR and in patients with SEORA, no significant difference in allele frequency or genotype was found.69

The role of triggers in the pathogenesis of PMR and SEORA is also unclear. A number of infectious and environmental agents have been suggested, including immune adjuvants present in vaccines,70 but data in the literature are mostly anecdotal and should be confirmed using large cohorts.69

Of greater interest is the characterisation of the type of inflammatory cells occurring in PMR and in SEORA. PMR is characterised by the presence of macrophages and T lymphocytes, with few neutrophils, and no B cells or natural killer (NK) cells.71 Instead, NK cells and B cells are present in the synovial fluids of RA patients and a strong correlation with severity and disease duration has recently been confirmed.72 NK cells are considered to be important in bone destruction that is, by definition, absent in PMR.56,57

THERAPEUTIC DIFFERENCES AND SIMILARITIES

Steroid Treatment

Treatment with oral prednisolone, with a starting dose of 12.5–25.0 mg, is the main step in the management of PMR.73 However, the above suggested initial doses should be adjusted individually according to the patient’s BMI, presence of comorbid diseases, and risk of steroid-related side effects.74 Although the EULAR/ACR recommendations for the management of PMR suggest using single rather than divided daily steroid doses, based on some experts’ opinions, patients may benefit from divided doses of prednisolone in some occasions. The starting doses for treatment of PMR and subsequent tapering regimens have not been studied thoroughly; however, maintaining the initial doses for 3–4 weeks before following up with tapering doses to 10 mg prednisolone within 4–8 weeks has been recommended.73,74 Subsequently, it has been recommended that prednisone be decreased by 2.5 mg every 2–4 weeks until the patient is at 10 mg daily, followed by the reduction of the daily dose of prednisone by 1 mg per month. In cases of relapse, defined by recurrence of PMR symptoms together with an increase in acute phase reactants, oral prednisolone dose should be increased to pre-relapse dose and tapered afterwards to the dose at which the relapse occurred within 4–8 weeks.73 In some patients, small doses of GC are necessary for years or the entirety of the patient’s life.4,20

The role of systemic GC in the management of EORA is controversial.75 In accordance with the 2016 update of EULAR recommendations for the management of RA, short-term treatment with GC should be considered when initiating or changing synthetic DMARD, followed by rapid and clinically feasible tapering regimens.36 On the other hand, elderly patients are more susceptible to GC-related side effects, including but not limited to diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, and eye diseases. Therefore, the risk-benefit of steroid treatment for the individual patient should be assessed by the clinicians before initiation of the treatment.4,10,12,51

Non-Steroidal Treatment Options

In recent years, some non-steroidal treatment options have been proposed as GC-sparing drugs for PMR therapy, especially in patients with insufficient response or with relapsing disease. Methotrexate (MTX) has been studied in both randomised controlled trials and retrospective studies. In the 2015 EULAR/ACR recommendations, MTX in small doses (7.5–10.0 mg/week) is proposed as an initial therapy concomitantly to oral GC in case of risk factors for relapse, prolonged therapy, or serious adverse events, and during follow-up in cases of relapse, insufficient response to GC, or GC adverse events.73

Mizoribine (MRZ) is an oral immunosuppressive drug that has a mechanism of action similar to mycophenolate mofetil, with an inhibitory effect on inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. MRZ was evaluated as not inferior to MTX as a GC-sparing drug both in patients with PMR and in those with SEORA. Additionally, it was evaluated as having a higher safety profile.76 In patients with SEORA, MRZ can be an additional regimen to MTX therapy, especially when the latter is not very effective.77 However, MRZ is not available in several countries, with its predominate use being in Japan where it has been approved since 1984.

Data on other synthetic DMARD, such as hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, or leflunomide, are very scarce in patients with PMR. They are currently not considered as a therapeutic option for PMR. Similarly, the 2015 EULAR/ACR recommendations strongly advise against the use of TNFα inhibitors for the treatment of PMR.73,74 On the contrary, the effectiveness of synthetic and biological DMARD is well-documented in patients with SEORA.36,78 These therapeutic differences are a further, relevant point to the fact that PMR and SEORA are two distinct and separate diseases.

Finally, great attention has been paid to tocilizumab (TCZ), which is the first humanised anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody. To date, studies in PMR patients are still limited and TCZ cannot yet be recommended for routine treatment of isolated PMR.79 On the contrary, starting from 2008, TCZ was used in RA patients, and five randomised, double-blind, controlled, multicentre, Phase III, pivotal, clinical trials demonstrated its efficacy and safety in a range of patient populations, including inadequate responders to MTX and inadequate responders to TNF inhibitors. These trials were central to the approval of TCZ by regulatory authorities in the European Union (EU) and the USA for the treatment of RA.80

CONCLUSIONS

PMR and SEORA are two of the most frequent inflammatory rheumatologic diseases in the elderly patient. At first presentation, there are many similarities between PMR and SEORA, which may lead to a real diagnostic conundrum. Moreover, several prospective studies re-evaluated the final diagnosis in patients with PMR and found >20% of patients being diagnosed at a later date as having RA. Consequently, it is understandable that PMR and SEORA have been considered as components of a single disease process. In fact, PMR and SEORA must be considered two different diseases with many similarities. Some features (such as an erosive arthritis or the symmetrical involvement of metacarpophalangeal and/or proximal interphalangeal joints) can help differentiate these two inflammatory diseases, whereas findings of shoulder and hip US as well as 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT seem to be less specific.

As highlighted, a correct diagnosis also has relevant therapeutic implications. In PMR, GC are used for several months, and in some patients throughout life, and their side effects can induce significant comorbidities. On the contrary, in patients with SEORA, short term treatment with GC should be considered only when initiating or changing DMARD, followed by rapid tapering. Finally, most synthetic and biological DMARD are scarcely or totally ineffective in PMR and effective in SEORA.