INTRODUCTION

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a chronic systemic rheumatic disease, the hallmark manifestation of which is inflammatory back pain, and may also involve peripheral joints. There have been important developments in SpA, from its classification to the available imaging modalities, treatment options, and outcome measures. There has been a shift in the treatment paradigm to a more treat-to-target approach, where a level of a relevant outcome of the disease (e.g., disease activity) is defined as a goal to prevent consequent disability.1 The past typical example of a patient with SpA was a young person with irreversible deformation and functional disability that occurred over several years. Nowadays, the typical example of a patient with SpA is someone with a chronic but manageable disease who can remain active and participative. The reality is less ideal, since mandatory steps for a successful management (early recognition, referral, and treatment) are still undervalued. This review approaches the major ‘checkpoints’ that enable prompt and correct diagnosis and management of SpA.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE AND CLASSIFICATION OF SPONDYLOARTHRITIS

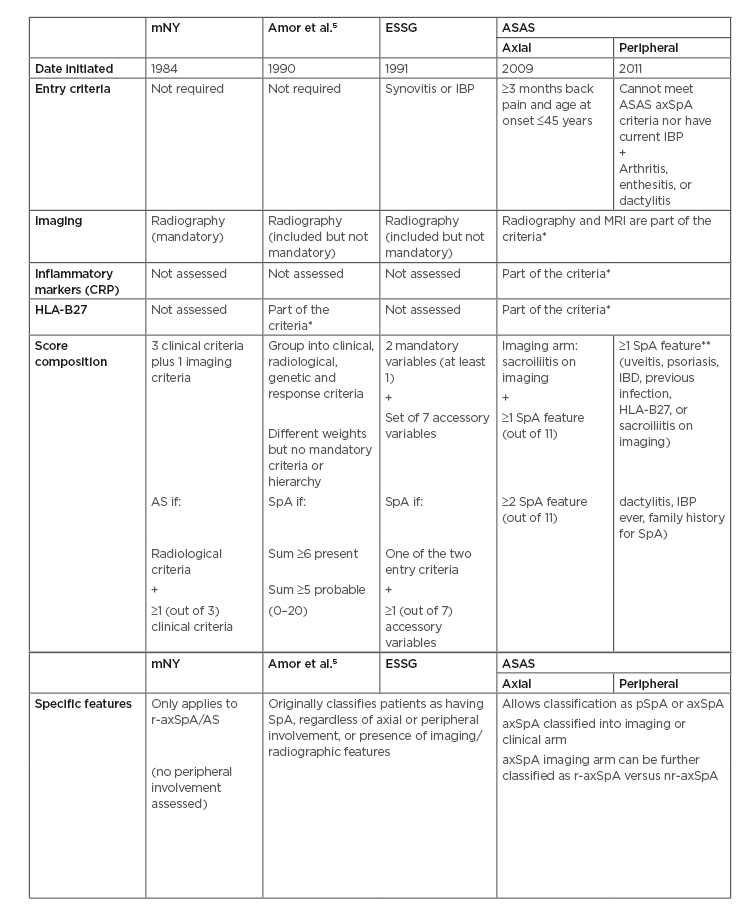

For decades, SpA was a ‘neglected’ disease, with only some isolated case reports of patients in advanced stages of the disease. Since the 1890s, efforts were made by Bechterew, Strumpell, and Pierre Marie to define ankylosing spondylitis (AS),2 a form of SpA characterised by radiographic sacroiliitis. Many societies attempted to develop classification criteria, drawing in new evidence from genetics, imaging, and extra-articular manifestations. Wright and Moll3 defined seronegative spondyloarthritis (seronegative referring to the lack of rheumatoid factor) as a set of different and independent diseases with common characteristics, namely: AS, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and a juvenile form of SpA. Many patients with inflammatory back pain without the typical imaging features were classified as ‘undifferentiated’ spondyloarthropathy in the late 1980s. However, in the early 1990s relevant classification criteria appeared: from the modified New York (mNY) criteria for AS,4 to the Amor et al.5 criteria and the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG)6 classification, the latter two of which addressed the whole spectrum of SpA including axial and peripheral manifestations. It was not until the 21st century that the Assessment of Spondylo Arthritis international Society (ASAS) group developed the ASAS classification criteria, which acknowledges SpA as a heterogeneous family that includes two distinct phenotypes: a predominant axial and a predominant peripheral form.

These criteria mainstreamed the concept of nonradiographic axial SpA (nr-axSpA) to define patients with axSpA without substantial radiographic sacroiliitis (as in classical AS) and also allowed the classification of a patient by imaging features or by clinical features only (Human leukocyte antigen [HLA]-B27] positive with two more features, regardless of imaging). nr-axSpA patients meet the ASAS criteria for axSpA but do not have radiographic sacroiliitis. Besides the classical radiographic findings used in the pre-existing mNY criteria, it also integrated MRI. MRI gives the possibility of identifying earlier stages of the disease (inflammation), other than the classical radiographic findings, reducing diagnostic delay. Table 1 shows the main features and differences of the main classification criteria for SpA.

Table 1: Comparing classification diagnosis criteria for spondyloarthritis.

AS: Ankylosing spondylitis; ASAS: The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria; axSpA: axial spondyloarthritis; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESSG: European Spondylarthropathy Study Group criteria; HLA-B27: Human leukocyte antigen-B27; mNY: modified New York criteria; nr-axSpA: nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis; pSpA: peripheral spondyloarthritis; r-axSpA: radiographic axial spondyloarthritis; SpA: spondyloarthritis; IBP: Inflammatory back pain.

*Even though it is possible to classify patients without these, many patients may be left unclassified in many situations if imaging and/or HLA-B27 status is lacking. Therefore, these are strongly recommended.

**SpA features (for axSpA): inflammatory back pain, arthritis, heel enthesitis, uveitis, dactylitis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, good response to NSAID, family history of spondyloarthritis, HLA-B27, and elevated C-reactive protein.

ASAS criteria moved from the concept of independent but related clinical entities (as in the Wright and Moll3 categories) into a concept of inter-related clinical manifestations. Classification criteria are not diagnostic criteria, although very often incorrectly used for diagnosis. Interestingly, there is no difference in the prevalence of axSpA between the sexes, although studies have identified male sex as a risk factor for radiographic progression, as well as HLA-B27, smoking, and mechanical stress. Evidence suggests that only some patients with nr-axSpA, especially if male, will evolve to AS.

DISEASE DIMENSIONS AND KEY MEASURES

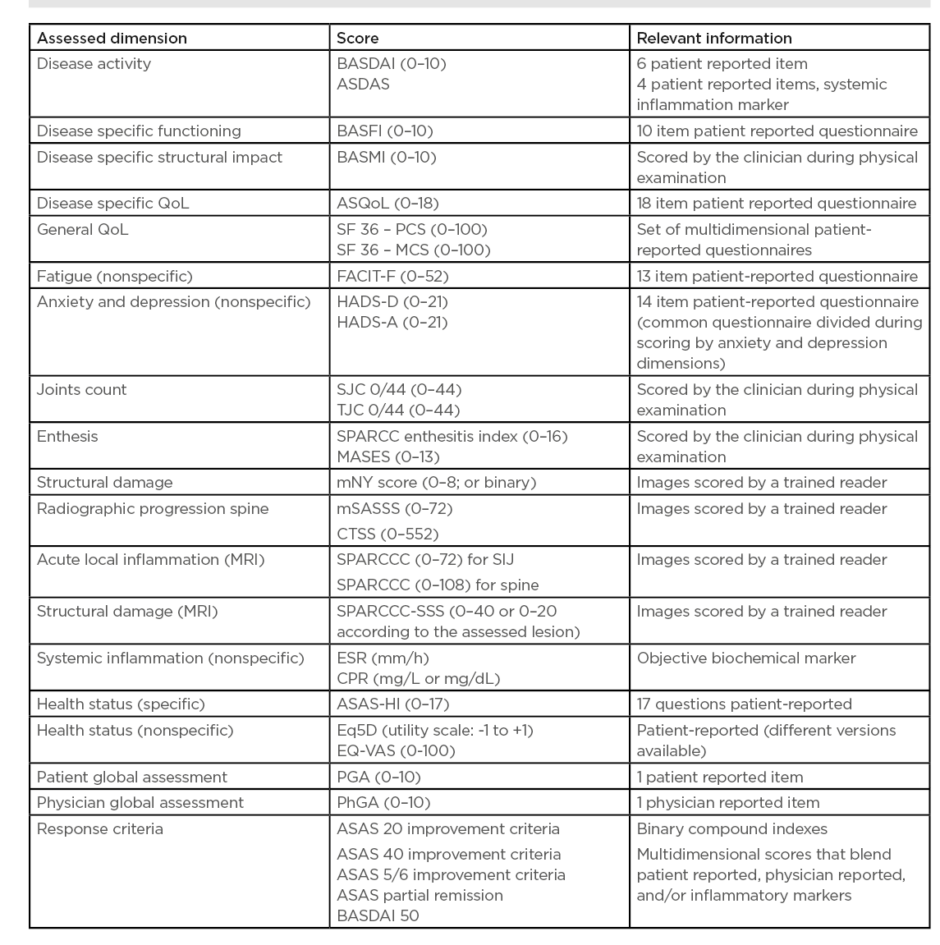

In order to treat-to-target it is essential to have an objective target. In the 1990s, the first disease-specific validated, compound patient-reported outcome for disease activity to become available was the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI),7 composed of six questions assessing fatigue, axial and peripheral pain/tenderness, and stiffness in a numeric scale.

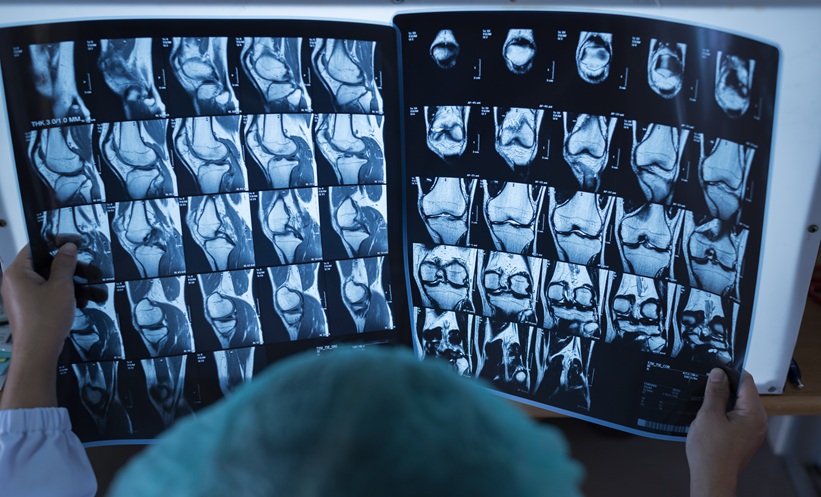

Decades later, a more sensitive disease activity measure appeared: the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS), based on three questions from the BASDAI, with patient global assessment and systemic inflammatory markers. Functioning is another central dimension in SpA. It is not infrequent that a patient with long-standing symptoms and structural damage may still have impaired functioning (measured by the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index [BASFI]), regardless of acute inflammation caused by structural damage. Structural impact over the sacroiliac joints as well as over the spine is a central feature in SpA. Besides the classical scores for radiographic structural progression, such as the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS), new validated inflammation/damage scores using MRI (e.g., the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada [SPARCC] scoring system) and CT (e.g., CT Syndesmophyte Score [CTSS]) have been validated and implemented in randomised control trials. However, MRI does have its disadvantages. It is an expensive technique, not universally available, many patients have contraindications, and some patients are not suitable for scanning because of claustrophobia or discomfort after a long time in the decubitus position.

Disease impact is not just limited to physical dimensions as the impact on overall health status is also crucial, leading to the development of the ASAS Health Index (ASAS-HI). The ASAS-HI is a 17 question-based compound patient-reported outcome that assesses the impact of SpA in different health dimensions, such as daily activities, fatigue, and interpersonal interactions.8 The main outcomes for the different dimensions are summarised in Table 2. The ASAS group developed a set of disease-specific quality standards to help improve the quality of healthcare provided to patients.9

Table 2: Spondyloarthritis dimensions and respective outcome measures.

ASAS-HI: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society Health Index; ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASQoL: Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life Questionnaire; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Metrology Index; CRP: C-reactive protein; CTSS: CT Syndesmophyte Score; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; Eq5D: Euroqol 5 dimensions; EQ-VAS: Euroqol visual analogue scale; FACIT-F: Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HADS-A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety; HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression; MASES: Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Index; mSASSS: modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score; SF36-MCS: Short Form Survey 36 items mental component score; SF36-PCS: Short Form Survey 36 items physical component score; SPARCC: Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada; SPARCC-SSS: Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium Of Canada MRI Sacroiliac Joint Structural; SJC: swollen joint count; TJC: tender joint count.

Considering the societal impact of SpA, studies such as the ASAS-Comorbidities in SpondyloArthritis (ASAS-COMOSpA) initiative demonstrated that disease activity is associated with poorer work participation (absenteeism and presenteeism), regardless of the clinical phenotype (radiographic or nonradiographic).10 This suggests that the better the disease activity control, the better the work participation.

TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS AND TREAT-TO-TARGET

For patients with active axial manifestation, current guidelines recommend nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) at maximum tolerated dosage as first-line treatment. If there is a failure of response to two different NSAID after 4 weeks (in total), then a biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (bDMARD) must be considered.11 The bDMARD may be a TNF inhibitor or an IL17 inhibitor. There is some evidence on the inhibition of radiographic progression by TNF.12 JAK inhibitors are a possible option, remaining controversial because of limited evidence.13 Treatment tapering remains another controversial issue because of conflicting and limited evidence.11-13

There is no satisfactory evidence in favour of oral steroids or conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) in axial disease. Patients with r-axSpA or nr-axSpA must be treated as soon as possible to improve disease activity levels and function.14 Physical activity and physical therapy should be considered on a case-by-case basis.11-13

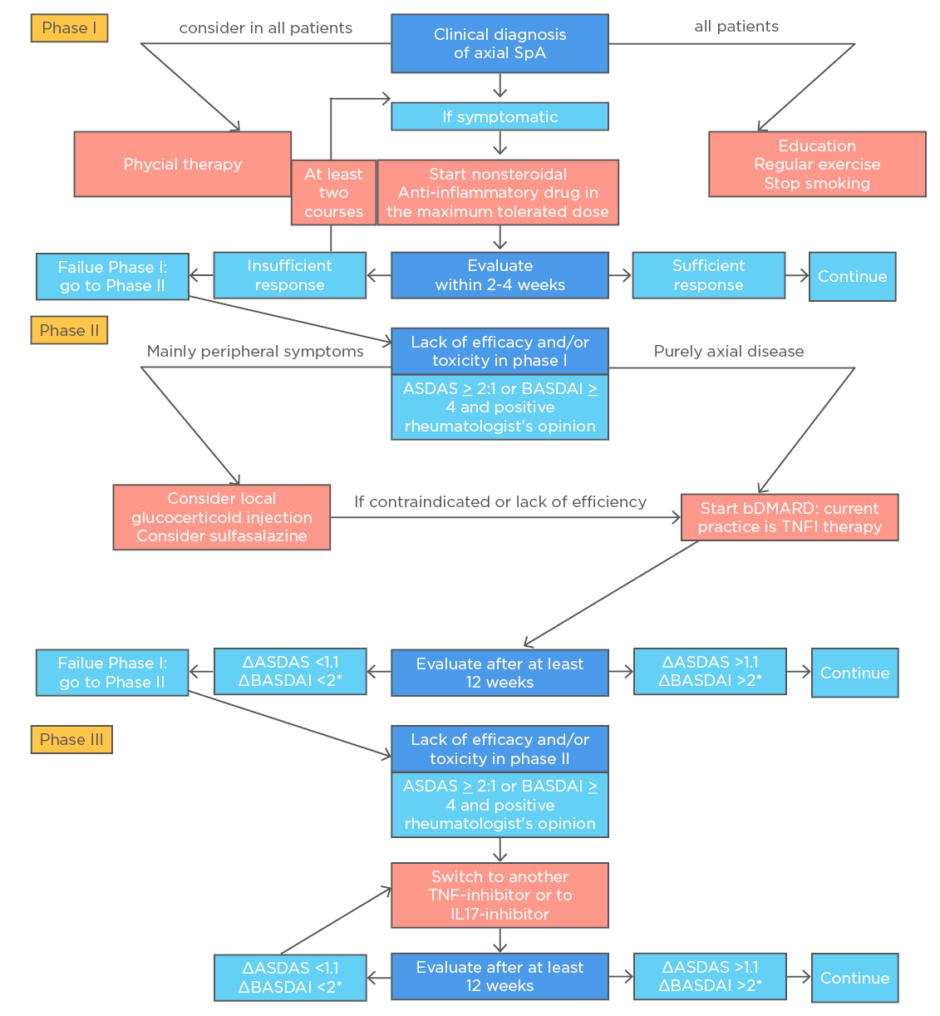

For peripheral manifestations, a csDMARD can be useful (e.g., sulfasalazine). Patients with active IBD, uveitis, or psoriasis should be referred to the respective specialty department. Figure 1 shows extracts from the latest treatment recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). Current treat-to-target recommendations state: “The goals of treating the patient with SpA or psoriatic arthritis are to optimise long-term health-related quality of life and social participation through control of signs and symptoms, prevention of structural damage, normalisation or preservation of function, avoidance of toxicities, and minimisation of comorbidities.”1

Figure 1: Algorithm based on the ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis.

ASAS: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; bDMARD: biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EULAR: the European League Against Rheumatism; IL17-inhibitor, interleukin-17 inhibitor; TNFi: tumour necrosis factor inhibitor.

*Either BASDAI or ASDAS, but the same outcome per patient.

Reproduced from van der Heijde D et al.11

The ideal goal should be sustained inactive disease/remission (ASDAS: <1.3 for axial manifestations), or at least low disease activity (ASDAS: <2.1). Although the ASAS improvement and partial remission criteria are widely used in randomised control trials, these are less discriminative than the respective ASDAS categories. Ideally, the target should include composite measures of disease that include clinical features, objective measures of inflammation, function, quality of life, and radiographic progression.

However, disease activity measures such as BASDAI and ASDAS do not consider all domains, especially extra-articular manifestations.14 Treat-to-target is based on the idea that the sooner the treatment is implemented, the lesser the disease progression and impairment; it was created by evidence extrapolated from psoriatic arthritis.1

OBSTACLES TO EARLY REFERRAL AND ADEQUATE TREATMENT

Since back pain is a very common symptom and SpA is a relatively rare disease, many patients overlook their symptoms and report them late. Many general practitioners may be unaware of the inflammatory characteristics of back pain as well as the extra-articular manifestations of axSpA. Even in developed countries such as Germany or the UK there is a median delay from symptom onset to clinical diagnosis of 2–5 years, which does not appear to have reduced over the last few years.15,16 Important clinical factors behind this delay included female sex, negative HLA-B27 status, presence of psoriasis or uveitis, and younger age at symptom onset. However, the presence of arthritis was associated with an earlier diagnosis.

Even after a correct diagnosis and referral, access to treatment is also a major issue in developing countries. The ASAS-COMOSpA initiative reported an unequal selection of treatment for SpA across different countries, regardless of clinical indication. In some countries, patients may be on ineffective csDMARD as an alternative to bDMARD, which has proven evidence, because of lack of access.17

CLINICAL CASE OF A HISTORICAL EXAMPLE

Herein the authors present the case of a 30-year-old female who visited her physician in the late 1980s complaining of back and neck pain. The pain had a strong inflammatory pattern, associated with 40 minutes of morning stiffness and pain in both ankles. She had an episode of acute inflammatory symptoms that lasted for a week and she responded to a short course of NSAID. Aside from being a heavy smoker, she had a job that involved manual labour. On subsequent follow-up, her symptoms were only partially relieved with NSAID, eventually with complete loss of response over time. Her radiographies had been unremarkable, with no sacroiliitis and no syndesmophytes. She had the HLA-B27 haplotype and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated (C-reactive protein was not performed at that time). After 10 years of follow-up the patient developed radiographic damage: radiographic sacroiliitis (meeting the mNY criteria for AS) and syndesmophytes. Her symptoms had been controlled with opioids because she could no longer tolerate long-term high-dose NSAID. Her symptoms changed from predominantly inflammatory to mostly mechanical, caused by structural damage. This led to her taking early medical retirement at the age of 45.

Reflection on the Case

Back in the 1980s when the patient described first presented, she did not meet the mNY criteria for AS and her disease would, at the most, be classified as ‘undifferentiated’ spondyloarthropathy. If the ESSG classification or Amor et al.5 criteria were available and used, the patient would have been correctly classified as having SpA (without a specific phenotype) and if the ASAS criteria were applied she would have met the criteria for nr-axSpA. If MRI imaging was appreciated as the gold standard and used at the time when the patient presented, it would have certainly added important information regarding local inflammation (bone marrow oedema) in this patient with symptomatic nonradiographic axial disease on initial presentation. Even if the patient had been correctly classified, there would have still been important limitations at that time, including the lack of objective disease activity measures (e.g., BASDAI or ASDAS) and an objective treatment target and, as well as the lack of effective treatments besides NSAID.

In spite of current obstacles, there is optimism on the availability of more sensitive classification criteria, better imaging techniques, and treatments (such as bDMARD) that will enhance the possibilities of improving care.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

Better classification criteria acknowledge the heterogeneity of spondylarthritis as a spectrum of disease and enable its early recognition.

All forms of axial spondylarthritis, regardless of radiographic sacroiliitis, belong to the same continuum. This means all require prompt referral to a rheumatologist, a correct diagnosis, and early management.

It is important to follow an objective treat-to-target approach in order to treat early, within the window of opportunity, minimising the risk of irreversible damage.

Treat-to-target strategies should be tailored to patient preferences and comorbidities in order to avoid toxicity and increase compliance.