INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) have demonstrated improved survival for multiple cancers.1 However, these new drug classes have led to increased immune-related adverse events (IrAE). Little is known about rheumatic adverse events with ICI therapy.2 Indeed, in Phase III studies, arthralgia, which includes all musculoskeletal disorders, was present in ˜5% of patients receiving ipilimumab for melanoma, 9–20% receiving pembrolizumab, and 5–16% receiving nivolumab for melanoma or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) versus <1% with placebo.3 However, these adverse events may be underestimated, and no clinical description was provided. Recently, one series of 13 patients with non-classified rheumatic IrAE was published;4 non-specific inflammatory arthritis developed in 9 patients without auto-antibodies and 4 presented sicca symptoms but did not fulfil the criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome. We report here cases of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) occurring after ICI treatment.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study on a collection of patients receiving an ICI in whom symptoms of arthritis or arthralgia developed and revealed a diagnosis of RA or PMR through the Gustave Roussy Cancer Center (Villejuif, France), which has established a national pharmacovigilance registry. A retrospective multicentre collection of observations through the Club Rhumatismes et Inflammation (CRI) network was performed, which is a section of the French Society of Rheumatology. Between September 2016 and January 2017, all rheumatologists and internal medicine practitioners registered on the CRI website, comprising almost 2,400 physicians all over France, were contacted via successive newsletters over 6 months to report cases.

RESULTS

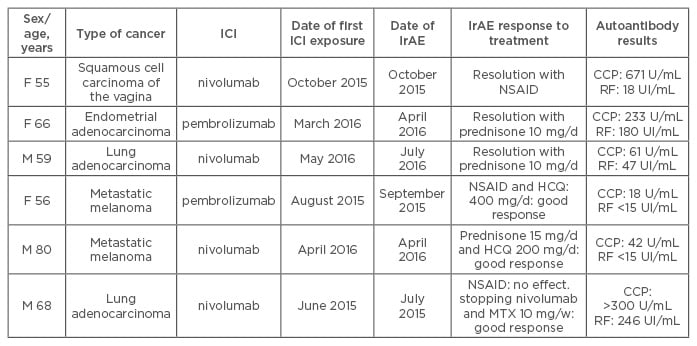

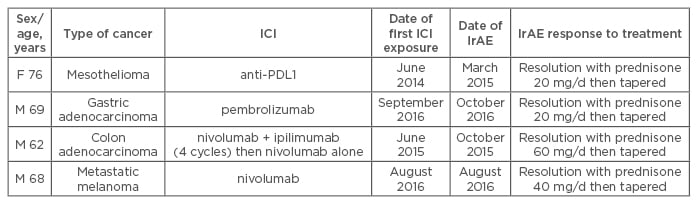

In 10 patients who received ICI therapy (anti-PD-1 or anti-PDL1 antibodies), RA or PMR developed at a median time of 1 month after exposure. The mean age of patients was 64 years and 60% were male. No patient had pre-existing rheumatic or autoimmune disease. RA developed in six patients; all were positive for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies and four for rheumatoid factor (RF). Anti-CCP antibodies were detected in two of the three patients that could be tested before immunotherapy. Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs were needed for 3 patients (hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate); the 3 others received corticosteroids or non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (Table 1). PMR was diagnosed in 4 patients, all responded to corticosteroids (Table 2). Despite these IrAEs, immunotherapy was pursued for all but one patient until cancer progression.

Table 1: Characteristics of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after immune-checkpoint inhibitor treatment for cancer.

F: Female; M: Male; RF: rheumatoid factor; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; MTX: methotrexate; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; IrAE: immune-related adverse event; CCP: cyclic citrullinated peptide; ICI: immune-checkpoint inhibitor.

Table 2: Characteristics of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica after immune-checkpoint inhibitor treatment for cancer.

F: Female; M: Male; RF: rheumatoid factor; PDL1: programmed cell death ligand protein 1; IrAE: immune-related adverse event; ICI: immune-checkpoint inhibitor.

CONCLUSION

This is the first description of RA occurring after ICI therapy for cancer. PMR can also occur after ICI, particularly after anti-PD-1 therapy. All cases responded to corticosteroids or with immunosuppressive therapy.

In our study, the 6 RA patients fulfilled the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria and were seropositive (anti-CCP positivity in all 6 and RF in 4). Anti-CCP antibodies were detected in 2 of the 3 patients (Patients 1, 4, and 5) with available serum samples before immunotherapy. Three patients were negative for RF before ICI therapy and 1 showed weak positivity (18 U/mL) afterward. The short time between ICI treatment and the development of joint symptoms and anti-CCP positivity before ICI therapy in 2 of the 3 patients suggested that some of these patients had a pre-RA status and that the treatment with ICI may have triggered the clinical disease. Indeed, studies have shown that antibodies (anti-CCP and RF) may be present several years before RA onset.5 Nevertheless, no patient presented arthralgia before ICI treatment. In conclusion, collaboration between rheumatologists and oncologists is crucial and could lead to better recognition and care of these patients.