BACKGROUND AND AIMS

An unhealthy diet is an important modifiable risk factor for hyperuricemia and gout and is also associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome (MetS), known risk factors for gout as well as for cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 The prevalence of CVD is considerably elevated in patients with gout.2 Nutrition plays a role in hyperuricemia and inflammation, directly and through metabolic dysregulation, liver, kidney, and gut health.3-7 A Mediterranean-style whole food plant-based diet (WFPD) has been shown to be effective for the treatment of other MetS- and obesity-related diseases,8-10 as well as (inflammatory) joint diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, leading to significantly decreased disease activity and improved metabolic status in both patient groups.11, 12 The authors, therefore, aimed to investigate the effect of a dietary intervention based on a WFPD on serum uric acid (SUA), gout disease activity, and cardiovascular risk in patients with gout.

METHODS

In the DIEGO (A DIEt for the treatment of GOut) pilot randomized clinical trial, patients with gout, hyperuricemia (males ≥0,42 mmol/L and females ≥0,36 mmol/L), abdominal obesity (waist circumference of ≥102 cm for males and ≥88 cm for females), and not receiving urate-lowering therapy were assigned to the DIEGO WFPD intervention group or a usual care control group. The DIEGO group received individual counseling from a registered dietitian (60 min at baseline, 30 min in Week 2, 4, 8, and 12) and followed a Mediterranean-style WFPD for 16 weeks. Participants were allowed to use their usual gout flare medication during a gout flare. The primary outcome was the SUA level. Secondary outcomes included gout disease activity, cardiovascular risk factors, and several other metabolic markers. An intention-to-treat analysis with a linear mixed model, adjusted for baseline values, was used to analyze the between-group differences of primary and secondary continuous outcomes at 16 weeks.

RESULTS

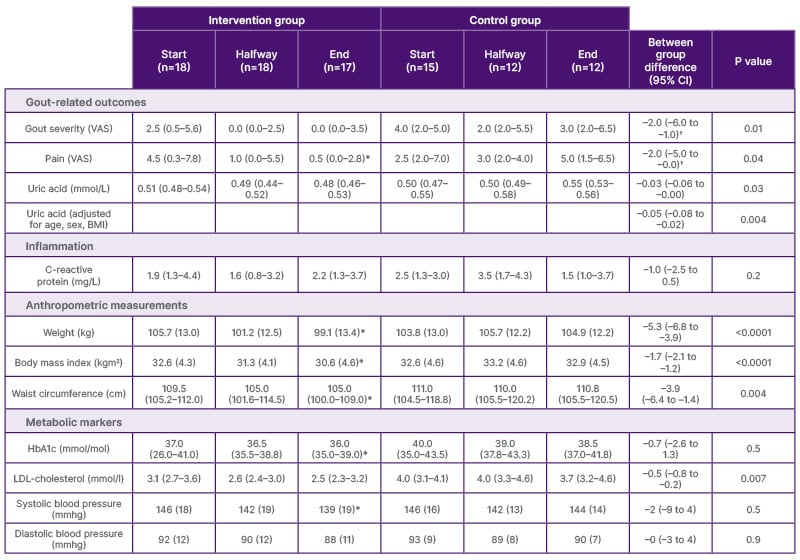

Of 54 people screened, 36 were randomized and 31 completed the study (DIEGO group: n=18). Overall, 92% of participants were male, with a mean (SD) age of 52 (12) years and a mean (SD) BMI of 33 (4) kg/m2. After 16 weeks, the DIEGO group had significantly lower SUA levels (-0.03 mmol/L: 95% CI: -0.06 to -0.00, p=0.03; -0.05 mmol/L: 95% CI -0.08 to -0.02, p=0.004; after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI) as compared to the control group (Table 1). In total, 23 gout flares occurred during the study, 11 in the DIEGO group and 12 in the control group. The mean (SD) duration (days) and flare intensity (Visual Analogue Scale [VAS] range 0 least to 10 worst) in the DIEGO group were 5.6 (2.3) and 6.2 (1.8), respectively, versus 4.6 (2.7) and 6.7 (1.6) in the control group. Overall, gout severity and pain (VAS range 0 least to 10 worst) were significantly lower in the DIEGO group versus the control group: -2.0 (95% CI: -6.0 to -1.0) and -2.0 (95% CI: -5.0 to -0.0), respectively. Compared to the control group, the DIEGO group had a lower body weight, reduced waist circumference, and improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol at the end of the study. The changes in systolic blood pressure and hemoglobin A1C were not significantly different between the groups; however, the systolic blood pressure and hemoglobin A1C reduced significantly within the DIEGO group and not in the control group. C-reactive protein and diastolic blood pressure remained unchanged. No serious adverse events occurred during the study.

Table 1: Primary and secondary outcomes of the DIEGO trial.

Continuous variables are reported as mean (SD) when normally distributed or as median (IQR) when skewed. Between-group differences shown at the end of the dietary intervention were determined using the linear-mixed model adjusted for baseline values. Outcomes were similar after adjusting for sex, age, and baseline BMI (weight, BMI, and waist circumference not adjusted for BMI), except pain (non-significant after adjustment). Within-group differences were assessed with a paired t-test when normally distributed or a Wilcoxon rank test when skewed. For variables in which model assumptions were not met (?) a linear-mixed model was performed after log(x + 1) transformation and between differences were reported as median difference determined using a Wilcoxon test (p values from the linear mixed model are shown, all were similar to the Wilcoxon test). VAS scores range from 0 (least) to 10 (worst). Significant within-group differences were reported (*) when p<0.05.

*Significant within-group differences.

†Variables in which model assumptions were not met.

HbA1c: hemoglobin A1C; IQR: interquartile range; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

CONCLUSION

The Mediterranean-style WFPD significantly decreased SUA in patients with gout and abdominal obesity. In addition, following the Mediterranean-style WFPD resulted in decreased gout severity and pain, significant weight loss, decreased waist circumference, and improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, thus reducing the risk for CVD.