BACKGROUND AND AIMS

The incidence of tuberculosis (TB) in England has decreased annually since 2011. However, the time from symptom onset to treatment initiation remains stubbornly elevated.1 The average general practitioner in England will only see one case of TB every 7 years. Clinical heterogeneity and a lack of information about presentation to primary care compounds the difficulty in identifying potential cases. To improve the timely diagnosis of TB, the authors aimed to describe the primary care presentation of adults with TB in England.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Coded demographic information and 5 years of prediagnostic clinical data were extracted from English primary care records held by the nationally representative Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Aurum and Gold databases.2,3 All patients aged ≥18 years and diagnosed with TB from 2011–2020 were eligible. Thirty signs and symptoms of interest were identified through a rapid literature review, followed by discussion with patients and healthcare professionals. Data were extracted and processed using the data extraction for epidemiological research (DExtER) tool.4 Summary statistics and graphical methods were used to describe patients and their signs and symptoms, using Stata v17 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

In total, 14,571 cases and 67,605 symptom codes were identified. Age at diagnosis ranged from 18–95 years, and 45% were female. Approximately one-third identified as White, and a further third identified as South Asian. Additionally, 32% came from the most deprived decile in England, 24% had pulmonary disease, 11% had extra-pulmonary disease, and site was unspecified in 65%.

Cases experienced between zero (19.6% of cases) to 15 different symptoms, and 67% experienced one to four symptoms (median: 2; interquartile range: 2). Older adults, females, and those with comorbidities experienced a broader range of symptoms.

The three most commonly occurring symptoms were cough (seen in 5,389 cases and 16.3% of all symptoms), back pain (n=4,197; 21.7%), and abdominal pain (n=2,822; 8.5%). The three least commonly occurring symptoms were chills (n=43; 0.1%), renal masses (n=35; 0.1%), and spinal deformity (n=24; 0.1%). Symptoms normally associated with TB, such as weight loss (2.5% of symptoms), fever (3.3%), and night sweats (0.7%), were infrequent.

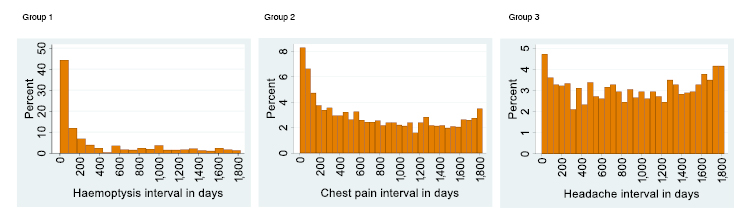

The interval between symptom onset and diagnosis ranged from 0 days to 5 years. Symptoms grossly followed one of three patterns (Figure 1). Group 1 symptoms (e.g., haemoptysis, anorexia, etc.) were characterised by being mostly recorded 6–7 months before diagnosis. Group 2 symptoms (chest pain, fatigue, pyuria, etc.) also had a peak in recording in the months before diagnosis, but this was not as distinct from the background rate, as in Group 1 symptoms. By contrast, no such pattern was seen in Group 3 symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain and headaches).

Figure 1: Distribution of Group 1, 2, and 3 symptoms and the time intervals at which they occurred.

Y axes are presented on different scales due to the large difference in numbers in the lead up to diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

TB is a heterogenous disease. Even in a large cohort of patients, typical symptoms are rarely recorded in primary care, and their absence cannot be interpreted as the absence of TB disease. There are also important variations in the presentation of subgroups, with distinct patterns of symptoms. The study is limited by using coded data, which may miss information about symptoms held in free text entries in electronic healthcare records.5 Further research could investigate the sequence in appearance of symptoms to further characterise the primary presentation of patients with TB. Guidelines for primary care should consider the findings of this study.