INTRODUCTION

Children with latent tuberculosis infection (LTI) represent a group of patients who are at risk of developing active tuberculosis (TB).1-3 The use of new immunological tests, such as Diaskintest® (Generium Pharmaceutical, Moscow, Russia), which uses a recombinant tuberculosis allergen based on Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific proteins: ESAT-6 and CFP-10, and QuantiFERON® (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), an immunological skin test, can improve diagnosis of LTI in children who have received the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination.4 The identification of risk factors for developing active TB in children with LTI is important for adequate maintenance of the disease. In a cohort retrospective-prospective study with multifactor analysis, we examined 624 children with LTI at 6 and 12 months and analysed risk factors for active TB development in these children.

METHODS

The St. Petersburg Research Institute of Phthisiopulmonology conducted a retrospective-prospective study during 2013–2016, involving 624 children (0–14 years old) with positive results from a tuberculin skin test and who had received the BCG vaccination. After complex diagnosis, 269 children were recognised as healthy, 127 (19.4%) children were diagnosed with LTI, and 258 (37.2%) were diagnosed with lung TB. We examined the children with LTI at both 6 and 12 months. The diagnostic complex included clinical assessment, immunological tests (Diaskintest), radiological methods including computed tomography (CT), and bacteriological methods. Multifactor analysis was applied to identify risk factors for children with LTI who were also at a high risk of developing active TB. Statistical analysis was performed by Statistic 7.0 and GraphPad Prism 6, and a chi-square test was used.

RESULTS

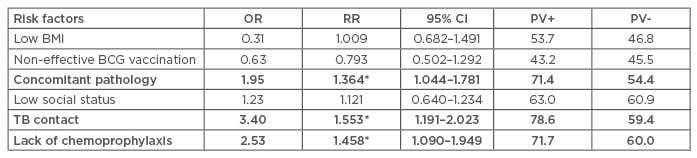

After observation, active lung TB was diagnosed in 76 (59.1%) children who had LTI at initial diagnosis; the relative risk (RR) was 0.6 and the chance of developing active disease (odds ratio [OR]) was 1.5. The analysis indicated the risk factors that could contribute to the development of TB in children with LTI. The most relevant high-risk factors for active TB development in children with LTI included the presence of comorbidities (OR: 1.95; RR: 1.36; 95% confidence interval [Cl]: 1.044–1.781), close contact with TB patients (OR: 3.40; RR: 1.553; 95% Cl: 1.191–2.023), and absence of chemoprophylaxis (OR: 2.53; RR: 1.458; 95% Cl: 1.090–1.949) (Table 1).

Table 1: Risk factors for developing active tuberculosis in children with latent tuberculosis infection.

BCG: Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio;

PV+: positive predictive test; PV-: negative predictive test; RR: relative risk; TB: tuberculosis.

*р<0.01 in comparison risk factors.

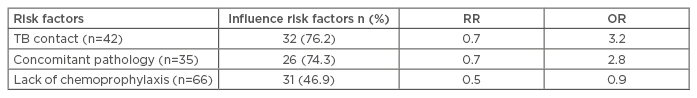

With regard to the children who developed active TB at 12 months, the risk factors also included the presence of comorbidities (74.3%; OR: 3.2), close contact with TB patients (76.2%; OR: 2.8), and the absence of chemoprophylaxis (76.6%; OR: 0.9) (Table 2). There are different schemes of chemoprophylaxis which differ in duration (3 and 6 months), as well as in the combination of anti-tuberculosis drugs (isoniazid, isoniazid and pyrazinamide, and isoniazid and rifampicin). However, in 48.1% (n=61) of cases, the parents of children with LTI refused chemoprophylaxis on their child’s behalf. Children who had a coincidence of comorbidities and close contact with TB patients developed active TB in 91.0% of cases.

Table 2: Influence of risk factors for the development of active tuberculosis in children with latent tuberculosis infection.

OR: odds ratio; RR: relative risk; TB: tuberculosis.

CONCLUSION

From our study, we concluded that children with LTI with the presence of comorbidities, close contact with TB patients, and who did not receive chemoprophylaxis were at a high risk of developing active TB within 1 year.