BACKGROUND

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHS) is characterized by persistent eosinophilia greater than 1,500 /µL for more than 6 months with organ system involvement in the absence of an explained cause.1 The organs involved can vary, affecting systems such as the lungs, skin, and cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular complications are a major source of morbidity and mortality, and prevalent in 40–50% of cases.1 The most characteristic cardiovascular abnormality is endomyocardial fibrosis, causing restrictive cardiomyopathy.1 However, patients are also prone to hypercoagulability, which in rare cases can manifest as ventricular thrombi.

CASE PRESENTATION

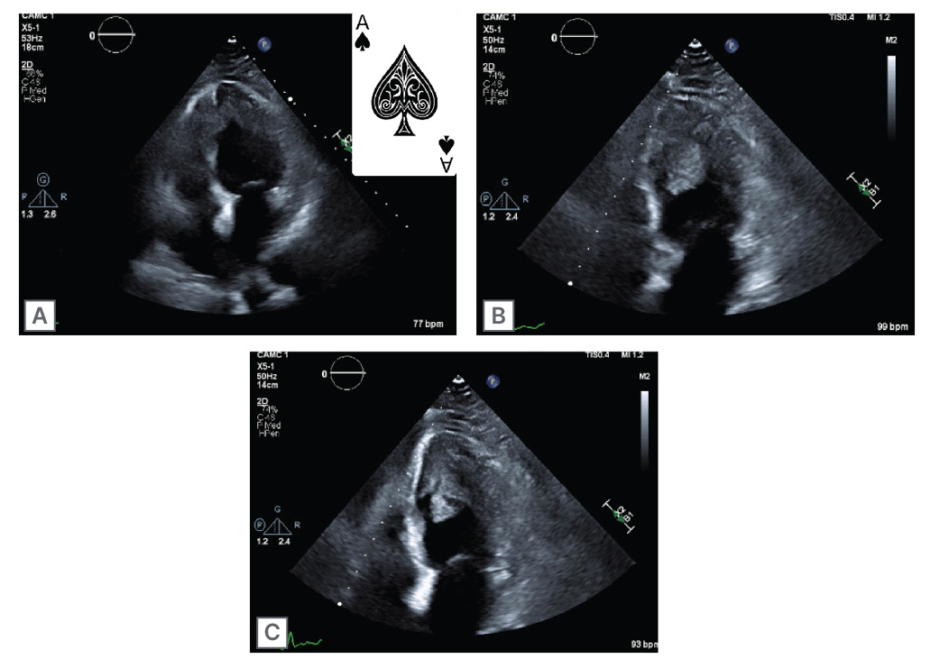

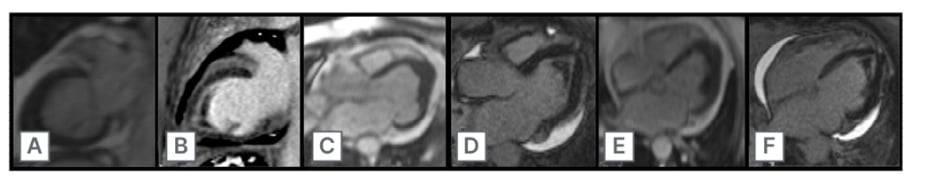

A 65-year-old female presented to the emergency department with complaints of worsening dyspnea and cough for 2 weeks. They were recently discharged following treatment for bilateral pneumonia, at which time they were noted to have an incidental left ventricular (LV) thrombus on an echocardiogram. Their symptoms improved with antibiotics, prednisone, and apixaban, but acutely worsened following completion of their treatment. Their laboratory work was remarkable for significant eosinophilia. A CT scan of the chest revealed recurrent bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and repeat echocardiogram revealed persistence of the LV thrombus with an obliterated apex in the shape of an ace of spades (Figure 1). Cardiac MRI confirmed the presence of a 1×2 cm LV thrombus with highly mobile components, along with diffuse subendocardial gadolinium enhancement consistent with IHS, with cardiac involvement (Figure 2). They were ultimately discharged on prednisone, mepolizumab, and warfarin with resolution of their eosinophilia. They returned a month later with multifocal embolic stroke. Repeat echocardiogram revealed the thrombus had enlarged to 3×2 cm. While on therapeutic low-molecular heparin, they developed acute right limb ischemia and underwent a right common and external iliac thrombectomy. Following embolectomy, they were ultimately discharged on dabigatran. They returned 2 months later with recurrent stroke-like symptoms. MRI revealed new multifocal infarcts, and echocardiography showed the thrombus had grown to 3×4 cm. Their anticoagulation was changed to enoxaparin, and they were scheduled for LV thrombectomy by cardiothoracic surgery. Unfortunately, they returned a week later secondary to a fall and were found to have a subdural hematoma with midline shift. They underwent two craniotomies with poor neurological response and were given comfort care.

Figure 1: Echocardiography showing four chamber view and ace of spades left ventricle (A);

two chamber view with left ventricular thrombus (B); and two chamber view with left ventricular thrombus (C).

Figure 2: Cardiac MRI showing two chamber view of late gadolinium enhancement (A–C),

and four chamber view of late gadolinium enhancement and left ventricular thrombus (D–F).

CONCLUSION

The cardiovascular complications in IHS typically involve a stepwise process. Initially, the eosinophils penetrate the myo- and endocardium, with subsequent eosinophilic degranulation and necrosis.2 The resulting necrosis allows fibrin deposition, beginning the formation of a thrombus.2 However, the thrombus in IHS is not solely comprised of platelets. A study by Leiferman et al.2 noted that the thrombi are comprised of intact eosinophils and eosinophilic granulation proteins.

It is thought that eosinophilic granules have components that inhibit thrombomodulin, enhancing thrombus formation.

This raises the question as to how thrombi in IHS should be treated given its composition. There are currently no guidelines for treatment. The authors’ patient had complications of the thrombus despite being on apixaban, warfarin, and heparin. In one case report, warfarin was given with successful reduction in an LV thrombus.3 However, there are several cases of continued thromboembolic phenomena despite adequate anticoagulation, while others report acute bleeds.2 As a result, current treatment should revolve around treating the underlying hypereosinophilic syndrome.4

First-line therapy consists of corticosteroids, with mepolizumab being considered an alternative second line option in corticosteroid sparing treatment.