ABSTRACT

National and European initiatives to drive quality improvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)1,2 have led to integrated care models.3,4 There is, however, no consensus on what these should comprise, and this remains a matter of debate and discussion. We presented our experience at the European Respiratory Society (ERS) International Congress 2018 in Paris, France, to illustrate how the successful integration of care requires the engagement of, and communication between, several healthcare providers and between the acute units, primary care, and community hospital settings. The same body of chest physicians, nurses, and allied healthcare professionals, whom the patient will see in the acute hospital and in the community clinics, also form part of the palliative service, where severely affected patients are discussed in a multidisciplinary forum and, where applicable, reviewed towards the end of life. This allows continuity of care across sites to be delivered. Patients can also self-refer themselves back into the system if they have been discharged and always remain at the centre of all decision-making.

In West Hertfordshire, UK, we introduced an integrated and seamless care pathway on 1st August 2017, based on the use of a simple double-sided pro forma, shared across all healthcare providers. Frontline staff in the emergency department can initiate the process, which is then carried forward by the specialist respiratory nurses during hospital admission and upon discharge, to be continued in the community. The tool encompasses all aspects of care, as well as functioning as a discharge bundle to ensure specific areas such as smoking cessation, palliative care (PC), and medication adherence are addressed and that the respiratory team is informed. Furthermore, the tool serves as a guide for COPD management, supported by an ongoing educational programme. An important measured outcome was the impact of this management on COPD exacerbations.

Symptom control is a frequently underestimated challenge in severe COPD,5 causing recurrent hospital admissions. PC needs to be reviewed and advanced care planning may help achieve better symptom management. We demonstrate how integration of respiratory and PC services can facilitate this process with regular team discussions and timely referral to psychology and well-being services.

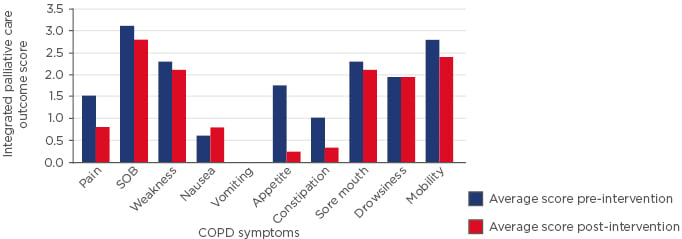

In the last year, >300 COPD exacerbations over the winter months were managed in the community alone with 1,013 COPD admissions in our acute hospital. After implementation of the service, a statistically significant reduction was noted in length of hospital stay in the winter of 2017 compared to 2016. Nonelective readmissions within 30 days after discharge were lower in 2018 compared to 2017. Also, COPD assessment tool score and symptom scores (measured using the integrated PC outcome scale) improved on receiving an integrated PC and respiratory intervention, such as the breathlessness service (Figure 1). Overall, 49.35% improved their anxiety score and 16.88% achieved the minimally clinical important difference of a reduction of ≥4 points.

Figure 1: Comparison of symptom scores in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients before and after integrated palliative care and respiratory interventions.

Integrated palliative care outcome score for symptoms performed before and after specialist combined respiratory and palliative care intervention.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SOB: shortness of breath.

We discussed with delegates at the ERS Congress how our approach, using the pathway throughout the patient journey and linking services across both acute and community sites, has led to the success of this model in improving quality of care and achieving the outcomes above. Although the feasibility of our model depended on a large pool of available staff, the initial investment has reaped benefits in a short time.

Looking to the future, we are excited about the opportunities and ventures that will allow further growth of our model, such as digital health platforms to improve patient self-management.