Meeting Summary

This symposium provided an overview of the efficacy and safety of multikinase inhibitors in colorectal cancer, including treatment sequencing, followed by an examination of the evidence in support of combination therapies and the use of regorafenib in gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) and other sarcomas. Prof Axel Grothey opened the symposium by introducing multikinase inhibitors and their role in treating malignancies. Prof Marc Ychou reviewed the Phase III studies supporting the use of regorafenib in later lines of therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Prof Grothey then discussed practical considerations when treating patients with regorafenib, including treatment sequencing and management of adverse events (AEs). Prof Jean-Yves Blay reviewed the efficacy and safety of regorafenib in treating GISTs and other sarcomas. Prof Eric Van Cutsem discussed potential future roles for regorafenib in treating difficult-to-treat malignancies such as advanced gastric and oesophagogastric cancer. Dr Jordi Bruix then demonstrated the possibility of using regorafenib as a second-line therapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have progressed following sorafenib therapy.

Introduction

Professor Axel Grothey

Oral multikinase inhibitors have the potential to improve outcomes for patients with a variety of malignancies, such as colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, HCC, and sarcomas, including GISTs. However, many oncologists remain unfamiliar with multikinase inhibitors and their role in treating gastrointestinal tumours, despite >2 years of real-world experience since regorafenib received marketing approval in Europe.

Maximising Patient Benefit with Third-line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Professor Marc Ychou

Regorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor that targets multiple proteins which target kinases involved in angiogenesis (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor receptors [VEGFR] 1–3 and TIE-2), tumour microenvironment (e.g. platelet-derived growth factor receptor [PDGFR]-β and fibroblast growth factor receptor), and oncogenesis (e.g. RAF, RET proto-oncogene, and stem cell growth factor receptor [KIT]).1

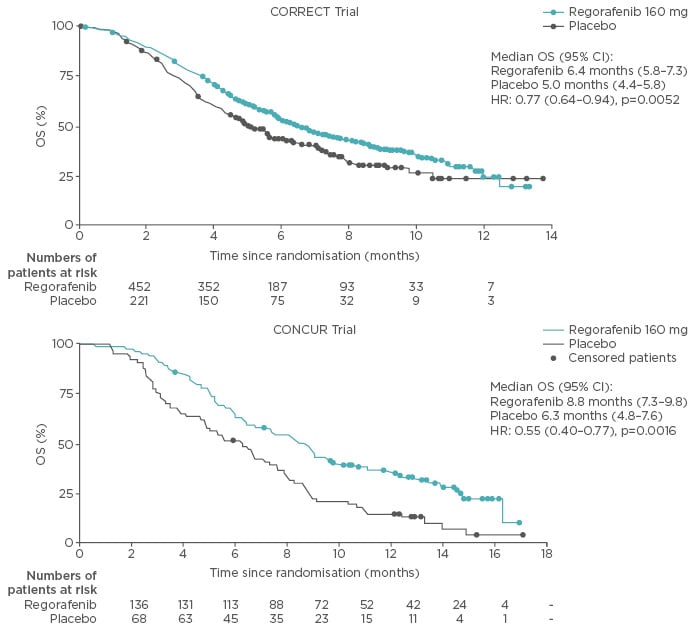

Regorafenib has demonstrated an overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) benefit in patients with mCRC who have progressed after standard therapies in the randomised, placebo-controlled CORRECT and CONCUR (performed in Asian patients) trials (Figure 1).2,3

Figure 1: Overall survival benefit for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were administered regorafenib as a third or fourth-line treatment option.

CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; OS: overall survival.

Adapted from Grothey et al. 2013 and Li et al. 2015.2,3

Interestingly, the lower hazard ratios (HRs) for OS in the CONCUR trial are largely thought to relate to lower levels of pretreatment with targeted therapies in CONCUR compared with the CORRECT trial, in which all patients were pretreated with bevacizumab.2,3 Comparable PFS outcomes have also been observed in the real-world setting in patients administered regorafenib in a third-line setting.4

A clinical benefit of regorafenib as a third or fourth-line therapy in patients with mCRC is the ability to achieve stable disease in a high percentage of patients. Tumour changes observed in patients with stable disease may provide early clinical markers for predicting therapeutic efficacy. One such marker is cavity formation within lesions, which is frequently observed in patients receiving anti-angiogenic therapy for primary lung tumours or pulmonary metastases.5 A retrospective analysis of 108 patients enrolled in the CORRECT study (75 and 33 patients in the regorafenib and placebo arms, respectively) found that cavitation of lung metastases after 8 weeks of treatment was a feature observed exclusively in patients treated with regorafenib (38.7% versus 0.0% of patients treated with regorafenib or placebo, respectively; p<0.01).6 Additionally, the presence of lung cavitation was associated with the absence of progressive disease at Week 8.7

Other potential markers have also been explored as indicators of drug efficacy. Some correlation was observed between several clinical characteristics (including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status [ECOG PS], the number of metastatic sites, and the time from diagnosis of metastatic disease) and extended PFS (>4 months) in the CORRECT study (representing 19% of patients in the regorafenib arm),8 and a retrospective study in Japan (N=121), which also reported that patients administered regorafenib with a decrease in serum cancer antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels of >10% had a longer PFS than those whose CA19-9 levels did not decrease after one cycle of regorafenib treatment.9 Additionally, the Colorectal Cancer Consortium Consensus for molecular subtypes has used a gene expression-based CRC classification to stratify patients with mCRC into four consensus molecular subtypes (CMS)1–4.10 Preliminary data suggest that CMS can be used as a prognostic marker for regorafenib efficacy, with greater OS and longer PFS being observed in patients with CMS2 and CMS4.11,12 However, this still needs to be validated in a large patient population.

In conclusion, regorafenib has demonstrated a benefit in improving survival in both Western and Asian populations.2,3 Imaging and molecular markers, such as cavitation of lung metastases and serum CA19-9 levels, are potential indicators of regorafenib efficacy.6,7,9 In the future, further research elucidating the molecular markers that predict drug efficacy will be beneficial for identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from regorafenib therapy.

Practical Treatment Sequencing in Third-Line Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Professor Axel Grothey

Improved outcomes in patients with mCRC are being driven by the sequential use of multiple lines of treatment.13 While guidelines provide direction on appropriate patient selection and treatment sequencing in first and second-line therapy, numerous options are now also available in the third and fourth lines, including regorafenib and TAS-102.14,15

Regorafenib has been shown to be efficacious in two large Phase III studies as a third or fourth-line treatment for patients with mCRC (52% of patients in CORRECT and 59% in CONCUR received ≤3 prior therapies for mCRC),2,3 particularly in patients who have been less heavily pretreated with targeted therapies.16 While oncologists can be wary of treatment-related AEs, regorafenib has a different mechanism of action and AE profile compared with chemotherapy, which may be beneficial, particularly for patients with myelosuppression.2,3,17 Regorafenib treatment may also offer an opportunity for patients to have a break from chemotherapy, before being re-challenged, if appropriate.2,18

Patients selected for regorafenib therapy should generally be less heavily pretreated, have an ECOG PS of 0 or 1, and be capable of understanding and managing treatment-related AEs.19 Fatigue and hand–foot skin reactions tend to appear early in patients treated with regorafenib, so patients should be educated on how to manage these AEs.19 For example, patients may be advised to remove calluses, dead skin, make their skin smoother, and wear comfortable shoes.19 Reminding patients that they may experience fatigue and voice changes also allows them to prepare for therapy.19

Regular and frequent monitoring (weekly during the first 2 months) of patients treated with regorafenib is recommended so that therapy can be interrupted or reduced before any serious AEs occur.19 The dose of regorafenib can also be titrated to meet the needs of individual patients.1,19

Patients whose disease progressed following regorafenib therapy can subsequently be treated with chemotherapy. In the CORRECT study, 26% of patients were treated with chemotherapy following regorafenib.2 In the real-world experience (Mayo Clinic, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Southern California, California, USA; N=173), it was found that 37% of patients treated with regorafenib went on to receive subsequent therapy (either standard chemotherapy or an investigational therapy in a clinical trial), with disease control achieved in 61% of patients treated with chemotherapy after regorafenib.20

TAS-102 remains a treatment option for patients who have progressed on regorafenib. In the randomised, placebo-controlled Phase III RECOURSE study, the clinical benefit associated with TAS-102 was maintained irrespective of prior treatment with regorafenib.17 Data from a small retrospective Japanese study (N=43) indicated that better outcomes are observed with TAS-102 treatment in regorafenib-pretreated versus regorafenib-naïve patients.21 Furthermore, patients who were administered regorafenib before TAS-102 had increased OS.21

Further investigation is needed regarding the use of regorafenib in combination with other regimens, including chemotherapy and targeted therapies.22-24 For example, second-line therapy with regorafenib (160 mg Days 4–10 and 18–24) in combination with FOLFIRI (Days 1–2 and 15–16) significantly increased PFS (primary endpoint), but not OS, compared with FOLFIRI alone in patients with mCRC who have progressed following first-line oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, and was generally well-tolerated with little increase compared with the control chemotherapy regimen.25 However, more prospective data are required in this realm before it is fully integrated into clinical practice. Furthermore, preclinical studies combining anti-VEGF therapy with immune checkpoint blockade suggest a favourable anti-tumour response, and preclinical data indicate that, in theory, regorafenib may enhance anti-tumour activity when combined with these therapies.24

Therefore, while regorafenib is recommended as a third or fourth-line treatment for patients with mCRC, treatment sequencing and the timing of later lines of treatment should be considered when attempting to achieve optimal survival outcomes. Future research will further clarify the role of regorafenib in treating patients with mCRC, including optimal dosing combination therapies.24,25

Targeting Kinase Pathways to Treat Progressive Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumours and Other Sarcomas

Professor Jean-Yves Blay

Sarcomas are a relatively rare form of cancer, accounting for approximately 1% of all tumours.26 GISTs are the most common sarcomas, and are most frequently driven by gain-of-function mutations in KIT and PDGFRA.27

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib is the standard first-line therapy for patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GISTs.28,29 However, the impact of targeted treatment with imatinib depends on the nature of the underlying mutation. For example, imatinib 400 mg is effective when treating most GISTs, but patients with exon 9 mutations require 800 mg to achieve optimum PFS. In addition, certain gene mutations confer resistance to imatinib, particularly mutations involving PDGFRA, and these more difficult-to-treat GISTs require different treatment approaches.

Oral multikinase inhibitors, such as sunitinib and regorafenib, are second and third-line treatment options, respectively, for patients with GISTs who have progressed following imatinib treatment.30 However, resistance to treatment with TKIs can emerge through the clonal selection of additional mutations, mostly in exon 17 and 18, or 13 and 14, of KIT. Therefore, the kinase inhibition profiles of multikinase inhibitors are clinically important.

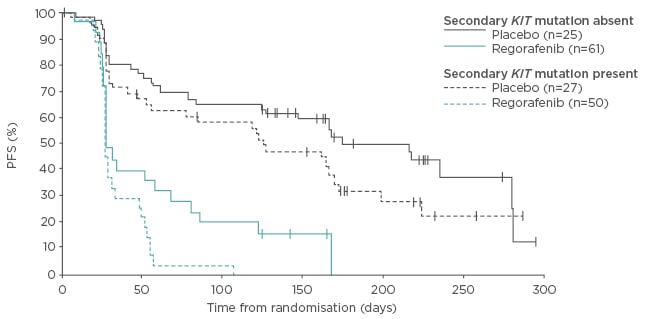

The benefits of regorafenib in treating advanced GISTs have been well-documented. In a single-arm Phase II study, patients with unresectable or metastatic GISTs (N=33) that had progressed following imatinib and sunitinib treatment, and were treated with regorafenib, had a PFS of 13.2 months and an OS of 25.0 months.31 The Phase III GRID study reported that regorafenib significantly improved PFS (HR: 0.27 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.19–0.39]) compared with placebo in patients with advanced GISTs that progressed after failure of imatinib and sunitinib.31 Of particular interest was that the activity of regorafenib was similar in patients with KIT exon 9 and exon 11 mutations (HR: 0.21 [95% CI: 0.098–0.458] for exon 11 mutations versus HR: 0.24 [95% CI: 0.07–0.88] for exon 9 mutations; Figure 2).32 Regorafenib was found to be efficacious in patients with previously treated GISTs, regardless of the presence of secondary KIT mutations.31,32 Furthermore, the AE profile of regorafenib was consistent with that observed in other studies, but the rate of discontinuation due to AEs was similar to placebo.31 Following on from these results, the efficacy and safety of alternating between imatinib and regorafenib therapy as a first-line therapy for patients with GISTs is being investigated in a Phase II trial.33

Figure 2: Progression-free survival in patients with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour with secondary KIT mutations.

PFS: progression-free survival.

Adapted from Demetri et al. 2013.32

Regorafenib may also be effective in treating patients with soft-tissue, visceral, and bone sarcomas. The PALETTE study demonstrated improved median PFS in patients with a soft-tissue sarcoma and progressive disease following treatment with chemotherapy, administered the multikinase inhibitor pazopanib compared with placebo (4.6 versus 1.6 months; HR: 0.31 [95% CI: 0.24–0.40], p<0.0001).34 Following this, the randomised Phase II REGO-SARC study explored regorafenib in doxorubicin-pretreated patients with a variety of soft-tissue sarcomas. There was no significant difference observed for the liposarcoma cohort but improvement in PFS compared with placebo was observed in:35

- Leiomyosarcoma (3.7 versus 1.8 months; HR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.26–0.80], p=0.005)

- Synovial sarcoma (5.6 versus 1.0 months; HR: 0.10 [95% CI: 0.03–0.35], p<0.00001)

- Other sarcomas (2.9 versus 1.0 months; HR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.25–0.82], p=0.006)

Overall, in a pooled analysis, regorafenib was found to increase PFS for non-adipocytic sarcoma (4.0 versus 1.0 months; HR: 0.36 [95% CI: 0.26–0.53], p<0.0001) and exhibited a trend towards increased OS (13.4 versus 9.0 months; HR: 0.67 [95% CI: 0.44–1.02], p=0.06). In this study, the AE profile was consistent with the known safety profile of regorafenib.1,35

Further investigations of the role of regorafenib in treating patients with metastatic bone sarcomas that cannot be cured by surgery or radiotherapy are also currently underway in the REGOBONE study.36 Patients are currently being randomised to regorafenib or placebo and data from this study will be disseminated in due course.

Regorafenib therefore offers a potential treatment option for patients with GISTs who have progressed following prior TKI therapy or who present with secondary resistance mutations.31,33 Likewise, regorafenib may offer a potential treatment option for patients with other soft tissue sarcomas or bone sarcoma, and studies of the efficacy and safety of regorafenib in these patients are ongoing.35,36

The Emerging Role of Multikinase Inhibitors for Treatment of Refractory Advanced Oesophagogastric Cancer

Professor Eric Van Cutsem

Gastric and oesophageal cancers are common causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide37 yet relatively few treatment options are available. Surgical resection offers the only potentially curative option, although many patients present with advanced disease or develop metastases post-resection.38,39 Multikinase inhibitors, such as regorafenib, represent a potential therapeutic option for patients for whom curative resection is not an option.

Current treatment options for advanced oesophagogastric cancer either inhibit the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) or act by antagonising VEGFR2. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommend trastuzumab in combination with doublet chemotherapy as a first-line treatment option for patients with HER2-positive gastric cancer,39 but for patients with HER2-negative tumours, ramucirumab, an anti-VEGFR2 monoclonal antibody, is the only approved targeted therapy.40

For patients with advanced gastric cancer, an extensively targeted approach aimed at selectively inhibiting VEGFR2 is an alternative treatment option. Apatinib, a TKI that targets endothelial migration and proliferation, is believed to be effective in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.41 In a Chinese Phase III study, apatinib significantly increased OS by 1.8 months compared with patients administered a placebo to 6.5 months (HR: 0.71 [95% CI: 0.54–0.94], p=0.015), making apatinib a potentially attractive treatment option for patients with advanced gastric cancer.42 The randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II INTEGRATE study investigated regorafenib in patients with a metastatic or locally recurrent gastric or oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma that were refractory to first or second-line chemotherapy (N=152 [regorafenib, n=100; placebo, n=52]) as the molecular targets of regorafenib include kinases that act downstream from VEGFR2.43 In this study, regorafenib treatment resulted in a significant increase in PFS versus placebo (2.6 versus 0.9 months; HR: 0.40 [95% CI: 0.28–0.59], p<0.001) and a non-significant longer trend in OS.43 Additionally, regorafenib was generally well-tolerated, with an AE profile that was consistent with those previously reported in other studies.2,3,43 Following this data, the Phase III INTEGRATE II study regorafenib is further investigating the efficacy and safety of regorafenib in patients with treatment-refractory advanced oesophagogastric cancer.44

Therefore, while treatment with first-line trastuzumab and second-line ramucirumab is possible for patients with HER2-positive gastric cancer,39,40 oral multikinase inhibitors such as apatinib and regorafenib may offer an effective treatment option for patients with advanced oesophagogastric cancer who have limited treatment options.41-43

State-of-the-Art Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Doctor Jordi Bruix

Most physicians consider HCC to be a disease that lacks effective treatment options, despite the availability of therapies that effectively improve patient survival and as such are recommended in evidence-based practice guidelines. Treatment is recommended based on an HCC-specific staging model that delineates HCC into different evolutionary stages.45 Importantly, the pattern and location of disease in patients with HCC dictates whether surgical resection, transplantation, ablation, or transcatheter chemoembolisation is feasible, or whether the patient should be treated with systemic therapy.

Almost 10 years ago, a new era in the treatment of HCC was heralded when the first data indicating that sorafenib, a drug unsuitable for locoregional therapy, increased OS for both Western and Asian patients with HCC were disseminated.46,47 Since then all Phase III trials of novel systemic therapies for HCC have failed to improve outcomes in first or second-line settings. Hence, sorafenib was the sole systemic agent providing survival benefit.48-57 However, data from the Phase III placebo controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of regorafenib as a second-line treatment in patients with HCC who progressed following sorafenib therapy.58 In addition, the study showed a manageable safety profile, with drug-related AEs causing treatment interruption in 10% of patients. Quality of life, measured by patient-reported outcomes, was not affected by treatment.

In the randomised (2:1), double-blind RESORCE study, patients with HCC (Barcelona Liver Cancer Clinic Stage B or C disease who could not benefit from resection, local ablation, or transcatheter chemoembolisation; Child–Pugh A liver function) and documented radiological progression following sorafenib treatment were randomised to receive 4-week cycles of regorafenib 160 mg daily (3 weeks on/1 week off; n=379) or placebo (n=194) within 10 weeks of their last sorafenib dose.59 Importantly, patients enrolled in this study were required to have tolerated sorafenib therapy given that both treatments are TKIs.59 OS in patients treated with regorafenib significantly increased to 10.6 months compared with 7.8 months in the placebo arm (HR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.50–0.79], p<0.001).59 All subgroup analyses also indicated a favourable outcome in patients treated with regorafenib.59

A PFS benefit was observed in patients treated with regorafenib compared with placebo (3.1 versus 1.5 months; HR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.37–0.56], p<0.001).59 A comparable result was also observed when assessing time to progression (TTP) in patients treated with regorafenib or placebo (3.2 versus 1.5 months; HR: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.36–0.55], p<0.001).59 A consistent PFS and TTP benefit was also observed for all subgroups in the regorafenib treatment arm.59 The ORR and disease control rate were also significantly increased in patients treated with regorafenib compared with placebo, when assessed using either modified or revised (version 1.1) Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria.59 Notably, the disease control rate of 65% with regorafenib compared with 36% with placebo represented disease stabilisation in a greater proportion of patients (assessed using modified RECIST criteria; p<0.001), while the TTP was not different when using RECIST or mRECIST.59

Regorafenib treatment was well-tolerated, with 49% of regorafenib-treated patients maintaining the full dose of therapy throughout the study, and the AE profile was consistent with that observed in other studies.2,3,59 The most common AEs were hand–foot skin reactions, fatigue, and hypertension.59 Treatment-emergent and drug-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation in 25% and 10% of patients in the regorafenib arm, respectively, and regorafenib did not appear to affect liver function.59

Regorafenib is thus effective as a second-line treatment option for patients with HCC who have progressed following previous sorafenib treatment.59 Regorafenib is generally well-tolerated in patients who have tolerated sorafenib therapy and stabilises the disease in a high proportion of patients, with a significant and clinically relevant increase in TTP, PFS, and OS.59