Colorectal cancer survivors have an elevated risk of comorbid disease, particularly cardiovascular (CV) disease, due to both the age at diagnosis (around 60 years) and shared lifestyle risk factors; namely, being overweight/obese, physical inactivity, poor diet, and smoking.1,2 BMI is the strongest correlate of comorbid CV disease in cancer survivors.2 Comorbid chronic conditions can have a negative impact on colorectal cancer survival and can be a cause of death in these patients.3 In fact, coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in colorectal cancer survivors 10 years after diagnosis. There is mechanistic evidence that obesity induces alterations in proinflammatory cytokines, lipid metabolites, adipokines, and insulin growth factor signalling pathways.4

Health behaviours seem to have an impact on outcomes after the diagnosis of colorectal cancer.5 There is strong evidence of the benefits of physical activity in cancer outcomes after the diagnosis of colorectal cancer.6 Unfortunately, most of these studies were conducted using a questionnaire, which is very well-known to constitute an important bias, since patients overestimate physical activity and underestimate sedentarism.7 A number of studies have documented the prevalence of comorbid chronic conditions in colorectal cancer survivors.3 However, there is no study of cancer survivors that focusses on the current American Heart Association (AHA) policy on CV health. To define CV health, the Committee of the Strategic Planning Task Force of the AHA adopted positive language, defining health factors instead of risk factors, and health behaviours instead of risk behaviours.8 Whereas behaviours are modifiable, factors are not.

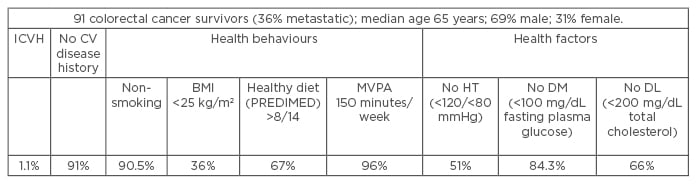

The objective of our study was to describe the CV health of a cohort of recently diagnosed colorectal cancer patients. The criteria used to define an ideal CV health in our sample were very restrictive. In order to adhere to current recommendations, ≥150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity needed to be recorded through accelerometers. Diet was evaluated using the PREDIMED questionnaire, which evaluated the adherence of participants to a Mediterranean diet. Patients who did not report CV risk factors had their values for blood pressure, BMI, glucose, and cholesterol measured at hospital (Table 1). Ideal CV health was considered only when both four behaviours and three health factors were present at the same time.

Table 1: The cardiovascular health of a cohort of patients with recently diagnosed colorectal cancer.

CV: cardiovascular; DL: dyslipidaemia; DM: diabetes mellitus; HT: hypertension; ICVH: ideal cardiovascular health; MVPA: moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

Of the 91 patients who were recruited, only 1 patient achieved seven metrics, which represented 1.1% of our sample having ideal CV health. Even when objectively measured, our sample was overall compliant with physical activity recommendations, confirming previous findings in Spanish cancer survivors.9 Being overweight/obese was the most prevalent unhealthy behaviour.

Becoming overweight or obese is the result of chronic energy imbalance. A significant controversy in the field is the so-called ‘obesity paradox’, which confers a better prognosis to obese metastatic colorectal cancer survivors.10 The relationships between energy balance and prognosis, sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and cancer outcomes, in addition to the biologic mechanisms that mediate this relationship, are promising areas that warrant additional investigation.