Abstract

Mucormycosis is an invasive fungal infection caused by opportunistic fungi of the phylum Glomeromycotan, subphylum Mucormycotina, mainly affecting individuals with immunosuppression. Cutaneous mucormycosis is the third most common clinical form of the disease preceded by pulmonary and rhinocerebral mucormycosis. The usual factors predisposing to this infection are individuals who are immunocompromised with conditions like HIV, haematological malignancies, and diabetes mellitus, but a significant proportion of patients are immunocompetent. The agents of mucormycosis are abundantly present in nature and are transmitted to the skin by direct inoculation. It may be due to needle sticks, stings, and bites by animals, motor-vehicle accidents, natural disasters, and burn injuries. The clinical presentation is non-specific, but an indurated plaque that rapidly evolves to necrosis (eschar) is a common finding. The infection can invade locally, and also penetrate into the adjacent fat, muscle, fascia, and bone, or become disseminated. It is difficult to diagnose because of the non-specific presentation of mucormycosis. Biopsy and culture should be performed. Treatment consists of multidisciplinary management, including surgical debridement, use of antifungal drugs (amphotericin B and posaconazole), and reversal of underlying risk factors, when possible. Mortality rates are significant, ranging from 4% to 10% in localised mucormycosis infection, but are lower than the other forms of the disease. The authors present a case here of a 38-year-old immunocompetent male with cutaneous mucormycosis at the interscapular region.

INTRODUCTION

Mucormycosis is an uncommon but emerging opportunistic fungal infection with high morbidity and mortality, feared by clinicians worldwide.1 It is a potentially lethal infection caused primarily by filamentous fungus Rhizopus, Mucor, and Lichtheimia species of the fungi of the order Mucorales.2-6 It usually affects patients with poorly controlled diabetes and individuals with immunosuppression.7-11 Frequent clinical presentations include rhino-cerebral, pulmonary, and cutaneous forms, and less frequently, gastrointestinal, disseminated, and miscellaneous forms.12-16

This case report will focus on cutaneous mucormycosis.

CASE REPORT

The authors had a 38-year-old patient presented to the clinic with the chief complaint of a painful indurated ulcer measuring 2×3 cm at the interscapular region, with pus discharge for 2 days. The patient had no history of diabetes, HIV infection, or prolonged corticosteroid therapy. The patient reported no trauma and was unsure about insect bite. The patient was admitted to wards and started on cefoperazone sulbactam and tramadol. Debridement of the ulcer was undertaken on Day 1 of admission. On post-operative Day 2, the entire wound was filled with pus and black discolouration. Clinical examination of the infected area revealed a large black necrotic patch measuring 6×6 cm with a satellite lesion measuring 1.5×2.5 cm at the interscapular region (Figure 1).

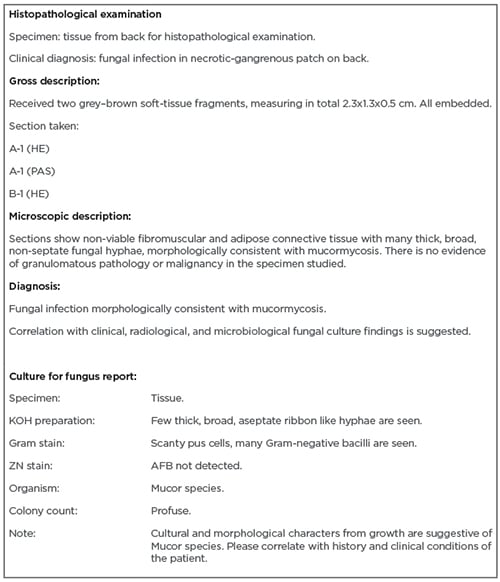

On the second hospital day, debridement was repeated, and the sample was sent for microbiology and histopathology work-up. Daily dressing of the wound was undertaken with betadine (povidone–iodine) and hydrogen peroxide, and the patient was continued on medications. On histopathology exam, the findings were thick, broad, non-septate fungal hyphae suggestive of mucormycosis (Box 1).

Systemic amphotericin B was started on the day mucormycosis was confirmed. Simultaneously, daily local dressings were undertaken for the wound with povidone–iodine, hydrogen peroxide, and normal saline, along with topical amphotericin B deoxycholate.

Extensive surgical debridement was done on the fourth hospital day, and the patient was continued on amphotericin B and routine wound care (Figure 2). The patient developed fever and chills which improved with supportive care. The patient’s wound showed improvement over next 3 weeks from pale granulation tissue to healthy granulation tissue (Figure 2). Split-skin grafting was performed using auto graft from the left thigh under general anaesthesia. The graft showed 100% uptake with a healthy wound (Figure 3).

The patient was continued on a single dose of amphotericin B at 1 mg/kg body weight as an infusion in 100 mL of 5% dextrose over 1–2 hours for a period of 45 days. The patient was doing well after 20 months since hospital discharge.

DISCUSSION

Mucormycosis is the common name given to several different diseases caused by fungi of the order Mucorales. Mucormycosis is an opportunistic fungal infection, usually occurring in patients who are immunocompromised but can infect healthy individuals as well. Predisposing factors for mucormycosis are uncontrolled diabetes, malignancies such as lymphoma and leukaemia, renal failure, organ transplant, long-term corticosteroid use and immunosuppressive therapy, cirrhosis, burns, protein–energy malnutrition, and AIDS. The current patient was a young male with full immunocompetency and no comorbidities.

In patients who are immunocompetent, phagocytosis of the spores prevents a fulminant course of the infection. Macrophages and neutrophils play an important role in this process. However, in individuals who are immunocompromised, lack of production and disruption of function of these immune cells lead to a rapid, progressive course of disease.

Manifestation of cutaneous mucormycosis is variable and can present gradually or as a fulminant disease leading to dissemination.17

This case report illustrates that the diagnosis of cutaneous mucormycosis can be difficult because initial symptoms are often non-specific and can mimic a variety of infectious skin diseases. This underlines the utmost importance of early harvesting of soft-tissue probes from the lesion site, in cases of progressive signs of infection.18 Biopsy samples should be attained early, so treatment can be initiated. Pathological features include angioinvasion, which initiates thrombosis and infarction of the affected surrounding tissues, leading to necrosis. The presence of wide, twisted fungal hyphae within blood vessels, with necrosis of the tissues supplied by affected vessels, is diagnostic for mucormycosis. Microbiological studies can then delineate the species of fungi involved.19

Figure 1: Clinical presentation of patient after first debridement.

Figure 2: Final debridement (left) and healthy granulation tissue (right).

Figure 3: Post-skin grafting.

Box 1: Histopathology and culture reports.

AFB: acid-fast bacillus; HE: haematoxylin and eosin; KOH: potassium hydroxide; PAS: periodic acid-Schiff; ZN: Ziehl-Neelsen.

A multi-modal approach in the management of cutaneous mucormycosis has been demonstrated to improve overall survival. This involves reversing any risks and underlying contributing comorbidities, systemic antifungal treatment, and aggressive surgical debridement. Debridement optimises cure rates by preventing further dissemination to deeper organs and manages the extensive necrosis occurring that may not be prevented by killing the organism with antifungals. When combined with early, high-dose systemic antifungal therapy, studies have shown that mortality can be reduced to less than 10%. Due to the resistance of Mucorales, the antifungal agent of choice is typically amphotericin B at high doses. However, because of its nephrotoxicity, renal function needs to be monitored. Novel regimens include using combination therapies (echinocandin or itraconazole) and adjunct treatments such as hyperbaric oxygen.20

CONCLUSIONS

The key to early detection and management of mucormycosis having a high index of suspicion for the disease. Ulcers with necrotic edges are not uncommon; however, its rapidly progressive nature should warrant suspicion of this disease. Identification of known risk factors, coupled with clinical findings and unresponsiveness to usual treatment, should prompt investigations. In this way, treatment can be initiated early to prevent a fulminant course of disease.