ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) can represent a suitable scenario for the use of bioresorbable vascular scaffold technologies because of the specific characteristics of STEMI patients (e.g., young age) and lesions (usually soft plaque with a necrotic core). Data from initial clinical experiences with a polymeric everolimus-eluting bioresorbable stent (BRS) (Absorb BVS®, Abbott Vascular, Chicago, Illinois, USA) in STEMI raised concerns among clinicians about the device safety because a noteworthy scaffold thrombosis (ScT) rate was reported at early, mid, and long-term (up to 3 years) follow-up after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI).1-3 Technical issues specifically related to the structural Absorb BRS features (e.g., thick polymeric struts and maximal post-expansion scaffold limits), as well as aspects related to the resorption process were advocated as probable causes for the BRS-related events reported. Nevertheless, prespecified technical suggestions of how to perform an optimal Absorb procedure in STEMI patients were lacking in each of the studies performed to date. Results from a multicentre, Italian, prospective evaluation of a standardised Absorb implantation strategy in 505 STEMI patients (17% of the overall population screened during the study period) suggested that the procedure was both feasible and associated with lower 30-day device-oriented composite endpoint (DOCE) and ScT rates compared to previous studies on the same topic.4,5 Although Absorb is no longer available on the market, further follow-up data are needed to understand the role of a specific BRS strategy (i.e., patient or lesion selection, implantation technique, and dual antiplatelet therapy regimen) in preventing BRS-related adverse events.

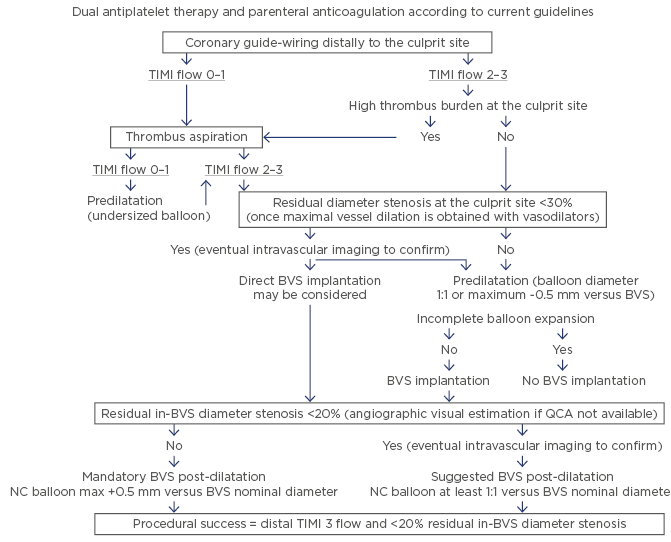

On this basis, the authors sought to assess the 1-year follow-up results following a prespecified Absorb implantation strategy in STEMI patients undergoing pPCI (Figure 1). According to the study protocol, direct Absorb implantation was feasible in 47 (9.3%) patients, while post-dilatation was performed in 468 (92.7%) cases, of whom 60.0% with an oversized (maximum diameter +0.5 mm compared to the Absorb nominal diameter implanted) non-compliant balloon. The hierarchical DOCE rate at 1-year follow-up was 1.2% (0.4% cardiac death, 0.4% target-vessel myocardial infarction, and 0.8% ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation) versus 0.6% at 30-day follow-up. Two episodes (0.4% of patients) of ScT (one probable subacute and one late definite) were reported. At 1-year follow-up, 99.2% of patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy (95% with ticagrelor or prasugrel). The limitations of this study include the observational nature, the lack of a direct comparison versus a current-generation drug-eluting stent, the short follow-up period, and the relatively selected STEMI cohort that precludes the generalisation of the outcomes reported in an all-comers STEMI population; however, the authors concluded that the prespecified Absorb implantation strategy in STEMI patients was associated with consistent low DOCE and ScT rates at 1-year follow-up. Longer term follow-up (3 and 5-year) is needed to assess the role of this strategy in preventing very late adverse events.6

Figure 1: The proposed management of a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patient undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention with Absorb implantation.

BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; NC: non-compliant; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography; TIMI: thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Adapted from Ielasi et al.4