Meeting Summary

The purpose of the meeting was to work towards unified best practice in the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). This centred on a theme of collaboration, with the intention of pooling and sharing the collective experience of healthcare professionals globally.

A talk from a patient representative introduced the concept of a patient-centric treatment approach and offered an alternative perspective on PBC care. This was followed by a review of the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) PBC guidelines, which highlighted the importance of risk stratification for individualised and optimal treatment. This led into a session related to biochemical response and the identification of patients suitable for second-line therapy.

Another key topic was ‘challenges in PBC management’, in which symptom management techniques focussing on pruritus and fatigue were highlighted. Following this, non-invasive imaging techniques and their evolving use in disease staging and risk assessment were discussed.

The advancing therapeutic landscape of PBC was presented, including discussion of emerging therapeutic targets such as farnesoid X receptors (FXR), fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF-19), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR). Obeticholic acid (OCALIVA®▼, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Inc., London, UK) is the first-in-class FXR agonist licensed for the second-line treatment of PBC, and its optimal therapeutic use was discussed through the presentation of clinical data and case studies.

Opening Remarks

Professor Dave Jones

Prof Jones opened the meeting, introducing the objective of working towards global best practice in PBC by pooling experience to improve the lives of patients with PBC.

MANAGEMENT OF PRIMARY BILIARY CHOLANGITIS: WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Working in Partnership: The Patient’s Perspective

Mr Achim Kautz

Speaking with 18 years’ experience working with liver disease patient groups, Mr Kautz asked delegates to consider the hidden burden on patients with PBC. PBC has a psychological burden that can leave patients feeling stigmatised, isolated, and misunderstood. These psychological aspects have been assessed in surveys throughout Europe, which indicate the extent of these issues.1-3 In an Italian survey (n=86), a significant proportion of patients stated they had a general concern about the impact of their disease on their future.2 In a German survey (n=577), almost 70% reported their PBC as having a negative impact on their quality of life (QoL).3 These findings were supported by a French survey (n=350) in which 68% of participants rated fear of progression as the most concerning aspect of PBC and 36% stated that PBC had impacted their lifestyle.4

While pruritus and abdominal pain are common in PBC, fatigue is considered to have the biggest impact on daily life.2,3 The lack of effective treatment options available for certain symptoms, including fatigue, can leave patients feeling frustrated.2 This can lead to patients undertaking self-management without communicating this to their clinician. Better collaboration between patients and clinicians is needed to understand symptom burden and improve management.

The European PBC Network is a consortium of PBC patient support and research organisations from across Europe. Its projects include publishing a patient-facing version of the EASL PBC guidelines, developing a PBC SharePoint, and using PBC Day 2018 to raise awareness. Through these activities, the group endeavours to facilitate a stronger patient–clinician partnership and strives towards an improved standard of care in PBC.

European Association for the Study of the Liver Guidelines: Top 10 Recommendations

Professor Gideon Hirschfield

The EASL clinical practice guidelines on PBC, published in 2017, were generated by evidence-based, expert consensus and received input from RARE-LIVER European Reference Network patient representatives.5 The full guidelines make comprehensive recommendations for PBC diagnosis and management.5 As chair of the guideline development group, Prof Hirschfield selected the 10 recommendations that he believed to be the most pertinent to PBC management in everyday clinical practice.

Diagnosis

Raised alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in combination with either antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) >1:40 or highly PBC-specific antinuclear antibodies are usually sufficient for diagnosing PBC. Alongside this, family history, physical examination, abdominal ultrasound, and serum tests are important. A liver biopsy is only required in the minority of AMA-negative patients.5

Lifelong Care

The chronic nature of PBC means that most patients experience a long disease journey. Disease course, stage, severity, and symptoms are varied, so patients require tailored follow-up and management.5

Risk Assessment

Therapy in PBC should aim to prevent end-stage complications of liver disease. Therefore, risk assessment is important to identify those at greatest risk of disease progression, namely patients with cirrhosis and inadequate biochemical response to therapy. Dependent on the predicted disease course, treatment can be escalated, or management altered. Risk assessment should consider both static and dynamic parameters (e.g., demographics, symptoms, serological profiles, serum markers, and histological features).5

Biochemical Response

All patients should be evaluated for their disease stage using a combination of non-invasive tests at baseline and during follow-up. After 1 year of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) therapy, treatment response should be assessed using biochemical response indices. The strongest risk factors for inadequate response are early age (<45 years) at diagnosis and advanced stage at presentation. Elevated serum bilirubin and ALP can be used as surrogate markers of outcome, and routine biochemistry and haematology indices should underpin the clinical approaches to stratify risk of disease progression.5

Ursodeoxycholic Acid

Oral UDCA (13–15 mg/kg/day) is an established effective first-line therapy.5 After 1 year of UDCA treatment, an inadequate biochemical response (such as ALP >1.67-fold higher than the upper limit of normal [ULN]) and/or elevated bilirubin indicates increased likeliness of disease progression and consequently reduced transplant-free survival.5,6 There is evidence for the addition of a second-line therapy for these patients. Inadequate response criteria have been combined into several varied qualitative binary systems (e.g., Toronto, Paris, and Barcelona) and two continuous scoring systems (UK-PBC and GLOBE scores).5

Obeticholic Acid

Oral obeticholic acid (OCALIVA▼) has been approved for use in combination with UDCA for PBC patients who have responded inadequately to UDCA, or as monotherapy in those intolerant to UDCA.5 In a Phase III study, obeticholic acid demonstrated biochemical efficacy compared with placebo, improving markers of disease activity such as ALP, AST, alanine transaminase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and bilirubin.5,7

Overlap with Autoimmune Hepatitis

PBC patients may present with features of autoimmune hepatitis; however, true overlap is rare. If overlap is suspected, liver biopsy is necessary for diagnosis and to guide treatment.5

Symptoms

Symptom severity does not correlate with disease stage. Therefore, all patients should be thoroughly evaluated for symptoms, particularly fatigue and pruritus, and their effect on QoL. A comprehensive and structured approach should be implemented, treating the symptoms themselves, their possible causes and associated comorbidities as per specific recommendations.5

Structured Care Pathways

EASL suggests the development of a care pathway for PBC. Efforts are currently underway to create this by translating the guidelines into concise clinical advice. This will reinforce the importance of considering a patient’s stage, symptoms, treatment, response, and risk for optimal care.

Patient Support

Patients should be offered access to patient support groups.5

Recognising Inadequate Response to Ursodeoxycholic Acid

Professor Jörg Petersen

Since UDCA became available for the treatment of PBC, validated surrogate endpoints, such as serum liver tests and liver stiffness measurements (LSM), have been used to assess disease progression.5 Multiple scoring systems exist for the assessment of biochemical response to UDCA. Common to all systems is the assessment of ALP and bilirubin and, based on these systems, 25–50% of patients are classed as inadequate responders to UDCA.5,8 This was demonstrated by a retrospective audit conducted by Prof Petersen of his patients (n=354). After 1 year, 40.2% of these patients had an inadequate response to UDCA according to the Paris II criteria (or 31.2% according to the Toronto criteria).

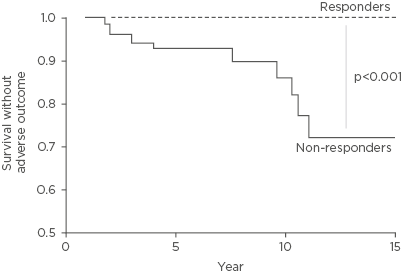

Data suggest that patients with an inadequate response to UDCA are likely to have shorter survival without adverse outcome than UDCA responders (Figure 1).9 All qualitative binary definitions of inadequate response predict clinical outcomes such as death and liver transplant, but some have other advantages; for example, the Toronto system is useful for predicting histological progression.5,9 GLOBE and UK-PBC are continuous scoring systems that, in comparison to definitions based on dichotomous criteria, incorporate prognostic variables (such as measures of treatment response). GLOBE allows comparison of transplant-free survival with a matched population to help classify patients as low or high risk.8 It has been demonstrated that those with an inadequate response to UDCA, compared to those with an adequate response, are more susceptible to hepatic complications.10

Figure 1: Survival rates without adverse outcome, according to 1-year biochemical response to UDCA as defined by the Paris II criteria.

The dotted line represents UDCA responders (n=79, 48%) and the solid line represents inadequate responders (n=86, 52%). Survival rates without adverse outcome for responders was 100% throughout follow-up and for inadequate responders it was 93% at 5 years, 87% at 10 years, and 74% at 15 years.

Adapted from Corpechot C et al.9

It is advised that clinicians implement whichever definition of inadequate response they find most useful. Risk stratification should be used to identify high-risk patients and treat them accordingly.5

CHALLENGES IN PRIMARY BILIARY CHOLANGITIS MANAGEMENT

Managing Pruritus

Dr Andreas Kremer

Pruritus in PBC primarily occurs on the limbs, palms, and soles of the feet, and is at its highest intensity in the evenings.11 In a UK survey (n=2,705), pruritus was reported by up to 70% of patients, and in a German survey (n=577), 56% considered their pruritus to be burdensome.3,12 The presence or absence of pruritus is unrelated to ALP level.3 Chronic pruritus is variable in duration and intensity, with higher intensity correlating to increased impact on QoL.13,14

There are multiple hypotheses for the cause of pruritus, as several possible pruritogenic substances have been found to be increased in cholestatic diseases. These include the indirect effect of bile salts, endogenous opioids, progesterone metabolites, and lysophosphatidic acid.11 However, except for lysophosphatidic acid, there is no correlation with itch intensity. Most of these theories also rely on a suggested indirect effect, which can be difficult to quantify. Therefore, there is no definitive answer, as a complex network of interacting factors is likely.11,14

The pruritogens responsible for chronic pruritus accumulate in the systemic circulation. Procedures such as albumin dialysis can lead to a dramatic reduction in pruritus measured by visual analogue scale. Nasobiliary drainage also results in relief of pruritus, demonstrating that pruritogens are secreted into bile and undergo enterohepatic circulation; however, the strong symptom relief from nasobiliary drainage is temporary.5,15

EASL guidelines recommend a stepwise approach to pruritus management, starting with first-line treatment with cholestyramine (4–16 g/day).5 Precautions for cholestyramine use are based on its ability to alter the absorption of other drugs, meaning that it must be administered separately.5 Recent trials of colesevelam have questioned the efficacy of anion-exchange resins due to results being similar to placebo.16

A second-line treatment option for pruritus is rifampicin (starting at 150 mg/day and titrating to 300 mg/day).5 Rifampicin improves pruritus via stimulation of transcription factors that influence secretory functions and bile acid (BA) metabolism.17 One prominent issue surrounding rifampicin is potential hepatotoxicity; however, studies have shown the incidence of this to be as low as 4.8%.18 It can also be mitigated by monitoring transaminases at 6 and 12 weeks of treatment and discontinuing the drug if liver deterioration occurs.5

Another factor to consider is that pruritogens modulate endogenous opioidergic and serotoninergic systems.13 Clinical trials of the μ-opioid antagonist naltrexone (25–50 mg/day) have demonstrated its ability to attenuate pruritus (although with lower efficacy than rifampicin).11,13 A possible side effect of this treatment is withdrawal-like symptoms, but these can be prevented through management of the dosing regimen.5,11,14

It is recommended that pruritus management is in line with guideline recommendations for cholestyramine and rifampicin use.5 Experimental drugs and invasive procedures are options in severe, unmanageable cases, but these should be reserved for specialist centres.5,13

Managing Fatigue

Professor Dave Jones

UK-PBC cohort data (n=2,353) showed that 35% of patients consider PBC to affect their QoL. In contrast, 45% stated their PBC causes minimal interference.19 There is evidence to suggest this split perception is subject to an age divide, with younger patients perceiving increased QoL impairment. Factors that may contribute to this include fatigue, cognitive symptoms, social and emotional dysfunction, and itch.20

The primary issues that need to be addressed to prevent negative impacts on QoL are common symptoms (e.g., pruritus and fatigue) and disease complications.20 Fatigue in PBC is unrelated to liver disease severity. Therefore, UDCA treatment does not improve fatigue, despite slowing disease progression.21

Fatigue is not just a psychological issue; it has a biological basis. Evaluation of muscle pH during exercise shows that PBC patients have profound acidosis and a severe and sustained drop in pH, meaning they use more energy to complete tasks relative to healthy controls.22 Exercise intervention techniques have been proposed to manage energy demand; however, there is limited evidence of the effect of this in PBC.23 At the central nervous system level, a small yet progressive decline in cognitive function in patients with PBC corresponds to dense white matter lesions in the brain.24

Fatigue can be managed practically through a combination of strategies, for example, the TrACE algorithm:

- Treat the treatable: all symptoms that negatively affect the patient should be addressed.5

- Ameliorate the ameliorable: depression is common in PBC patients, and patients who develop it should be offered appropriate therapy, particularly as it can exacerbate fatigue.

- Cope: strategies for coping with fatigue include pacing, day planning, and lifestyle adaptation.

- Empathise: symptoms should be managed with a clear approach tailored to each patient.

Clinicians need to appreciate the biological manifestations of fatigue and make sure a package of measures is implemented. Using a structured approach, such as TrACE, can reinforce management strategies and significantly improve fatigue.

Non-Invasive Imaging Technology

Professor Laurent Castera

Non-invasive tests are based on two different but complementary approaches: the measurement of liver function markers in the serum and LSM using transient elastography (TE). These techniques can be used for diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression as well as prognosis.5

Serum biomarker tests have good reproducibility, high applicability, and are generally low-cost and widely available. The disadvantages are that serum-biomarker tests are non-specific to the liver and have less accuracy for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.25,26 In contrast, TE has a high performance for assessing cirrhosis (with AUROC values >0.90) and is a point-of-care technique. Limitations include low applicability due to measurement failure or unreliability (20% of cases). TE can produce false positives and requires a dedicated device.25,26

There are several factors to consider when interpreting TE results. EASL-Latin American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH) guidelines state that for a reliable result the interquartile range should be <30% of the median value.26 The patient must fast before the test. Obesity can make performing TE difficult.27 Experience of the operator can also affect the validity of a result. Other confounding factors include extra-hepatic cholestasis, raised serum aminotransferases (>5-fold the ULN), right heart failure, and excessive alcohol intake.26

Most evidence for TE comes from studies of viral hepatitis, and although there are some data on PBC,28 there is no consensus on cut-offs, which vary between studies.29 TE performs better at excluding rather than confirming cirrhosis. When comparing TE with biomarker tests, two studies have shown that LSM outperforms other markers for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.28,29 Other imaging techniques are emerging, such as acoustic radiation force impulse and shear-wave elastography. These have a similar performance to TE, but the techniques can be implemented on a regular ultrasound machine. However, their quality criteria are currently not well-defined.26

Other uses of non-invasive imaging include investigating for portal hypertension and assessing the risk of varices. Patients with LSM <20 kPa and with a platelet count >150,000/μL blood have a very low risk of having oesophageal varices that require treatment.30 Using these criteria can result in safely avoiding 20% of endoscopies.31 LSM is significantly correlated with clinical, biological, and morphological parameters of disease, while specific cut-offs with a negative predictive value of >90% are a useful indication of complications (e.g., 27.5 kPa for oesophageal varices and 53.7 kPa for hepatocellular carcinoma).32 Over a 5-year period, LSM has been shown to be relatively stable in most non-cirrhotic PBC patients, whereas LSM is significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis.29 Baseline measurements of >9.6 kPa and change in LSM of >2.1 kPa per annum have prognostic value and would be a useful addition to PBC prognostic scoring systems.29 EASL recommends TE for disease staging and risk assessment of developing complications;5 however, the evidence for TE in PBC specifically remains limited.

EMERGING THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR PRIMARY BILIARY CHOLANGITIS

From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Practice: Licensed Therapies

Professor Ulrich Beuers

Primary Biliary Cholangitis Pathogenesis

In PBC, various factors have been discussed as potential triggers of immune-mediated bile duct injury that results in cholestasis.33 Among those, a defective bicarbonate umbrella due to impaired membrane expression of the chloride-bicarbonate anion exchanger AE2, leading to uncontrolled entry of protonated glycine conjugates of BA from bile into cholangiocytes that induce cellular damage (e.g., apoptosis and senescence), has recently received attention. Contributing to this effect is cholangiocellular overexpression of MiR-506 (located on the X-chromosome), which directly reduces AE2 expression and thereby biliary bicarbonate secretion. Following this, PDC-E2 peptides become aberrantly expressed on cholangiocyte membranes, possibly stimulating an immune response by T and B cells and thereby potentially aggravating apoptosis and senescence.33,34

Ursodeoxycholic Acid

UDCA improves the prognosis of patients with PBC and around 60% of those treated will reach a normal life expectancy.6 Putative mechanisms of UDCA action include stimulation of hepatocellular BA and cholangiocellular bicarbonate secretion, reduction of bile toxicity, and antiapoptotic effects.34,35 In experimental cholestasis it has been shown that UDCA conjugates act as post-transcriptional secretagogues, stimulating impaired insertion of transporter proteins into the canalicular membrane.34

The Farnesoid X Receptor

FXR is a nuclear hormone receptor with multiple target genes. Obeticholic acid is a potent agonist of FXR. FXR transcriptionally downregulates BA uptake transporters and inhibits CYP7A1 (integral to BA synthesis).35 Meanwhile, BA transformation and secretion is stimulated through increased expression of different pumps.36

FXR agonists protect against toxic effects of hydrophobic BA via:36

- Effects on BA homeostasis, including decreasing BA (re)uptake, reducing BA synthesis, and increasing BA secretion.

- Anti-inflammatory effects, including reducing inflammation in the liver and intestine.

The action of FXR agonists can work synergistically with the mechanism of UDCA, together preventing disease progression.

From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Practice: Novel Agents

Professor Cecília Rodrigues

Potential therapeutic targets in PBC include parts of the FGF-19 and PPAR pathways.35

Fibroblast Growth Factor-19

FGF-19 is involved in regulation of BA production through the gut–liver axis. FGF-19 binds to FGF receptor-4 and coreceptor β-Klotho. This leads to suppression of CYP7A1 and consequently to inhibition of BA synthesis.37 Parallel to this, MAP kinases are activated, which have been shown to play important roles in a variety of cellular functions.37,38 Enterokine-associated drugs are one of multiple classes of BA therapies currently in development.39

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Pathways

Anticholestatic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of PPARα activation include the suppression of NF-κB and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4, subsequently counteracting inflammation and reducing BA synthesis, while stimulating biliary phospholipid secretion via activation of MDR3. It is suggested that miRNA-21 ablation activation can suppress or activate PPARα.40 However, reduced necroinflammation of this type may require specific multitargeting.41

Obeticholic Acid Clinical Data

Professor Frederik Nevens

The cumulative incidence of first hepatic complications is higher in PBC patients with an inadequate response to UDCA than those with an adequate response (32.4% versus 6.2% at 10 years). Once patients have a hepatic complication, transplant-free survival rates are significantly reduced, compared with those who are complication-free (10.4% versus 85.3% at 10 years).10 This highlights a high-risk group that would benefit from second-line treatment with obeticholic acid (OCALIVA▼).42 For important information on dosing and safety, please refer to the prescribing information at the end of this article.

Phase II Studies

The efficacy and safety of obeticholic acid was explored in two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II studies. The primary endpoint in these studies was the change from baseline ALP in 12 weeks. The first study investigated obeticholic acid monotherapy. In the 10 mg/day obeticholic acid arm, median change in ALP was -54%.43,44 The second study assessed obeticholic acid in combination with UDCA. In the 10 mg obeticholic acid arm, there was a mean change of -24%.45,46

Phase III Studies

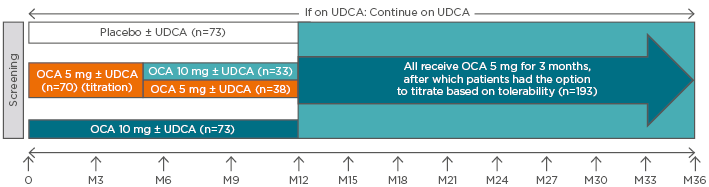

POISE was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III trial that assessed obeticholic acid efficacy over 12 months. It enrolled PBC patients with ALP ≥1.67-fold the ULN and/or total bilirubin greater than the ULN to <2-fold the ULN, who were either stable on UDCA or unable to tolerate UDCA. The study assigned 217 patients to three arms (Figure 2): placebo, obeticholic acid titration (5–10 mg/day), and obeticholic acid (10 mg/day). All groups also received UDCA, apart from the 7% of patients who could not tolerate it.7

Figure 2: POISE double-blind and open-label extension study designs.

The POISE double-blind period, which occurred during Months 0–12, consisted of three arms: placebo ± UDCA; obeticholic acid 10mg/day ± UDCA; and obeticholic acid titration ± UDCA (starting at 5 mg/day and titrating up to 10 mg/day, if tolerated). Dosing for the open-label extension was 5 mg/day ± UDCA for the first 3 months, with the option to subsequently titrate to 10 mg/day, based on tolerability. Patients receiving placebo during the 12-month, double-blind phase received obeticholic acid for 24 months during the open-label extension.

OCA: obeticholic acid; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid.

Adapted from Nevens et al.7 and Trauner M et al.47

There were significant reductions in ALP and stabilisation of bilirubin: 77% of patients in both obeticholic acid groups (versus 29% on placebo) achieved a reduction of ≥15% in ALP from baseline and maintained stable bilirubin levels over 12 months, compared with increasing bilirubin levels in patients receiving placebo. Reduction in ALP occurred as early as 2 weeks following treatment and continued for up to 12 months. With obeticholic acid treatment, compared with placebo, significant reductions were seen in biochemical markers such as AST, ALT, and GGT. The most common adverse reactions were pruritus and fatigue. However, in the obeticholic acid titration arm, the rate of treatment-emergent pruritus in patients without pruritus at baseline was comparable to placebo.7

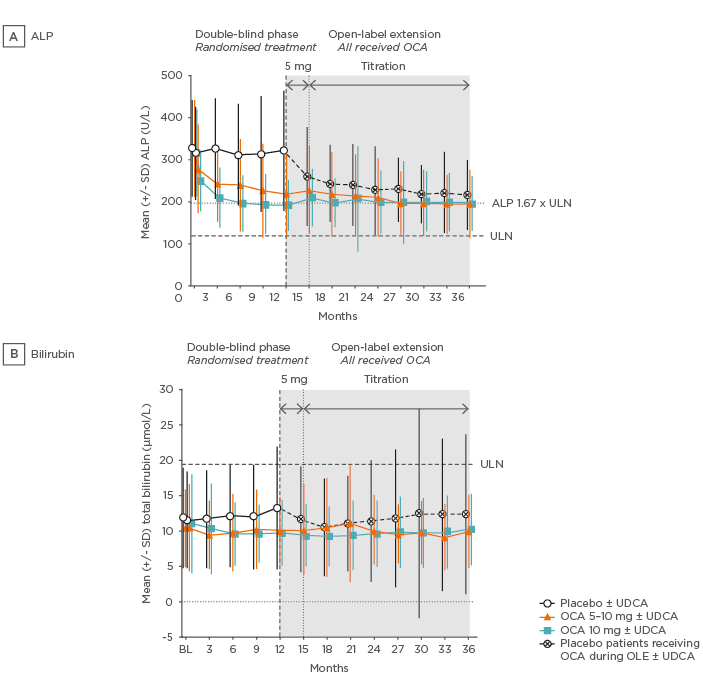

Of the patients who completed the double-blind phase, 97% chose to continue into the open-label extension (OLE).47 The OLE enrolled 193 patients who received obeticholic acid 5 mg ± UDCA (Figure 2), with the option to titrate to 10 mg after 3 months. Over 36 months of treatment (12 months double-blind and 24 months OLE), significant and sustained improvements were observed in multiple biochemical markers including ALP, ALT, GGT, and bilirubin (Figure 3).47 Improvement in these markers implies improvement in clinical outcomes.5

Figure 3: POISE open-label extension alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin data.

A) In the two obeticholic acid groups mean ALP was rapidly reduced in the first few weeks and continued to gradually decline, before stabilising thereafter. B) Mean total bilirubin was consistently below the ULN and remained stable in the obeticholic acid groups throughout the duration of study.

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; BL: baseline; OCA: obeticholic acid; SD: standard deviation; ULN: upper limit of normal.

Adapted from Trauner M et al. 47

The safety profile of obeticholic acid in the OLE was comparable to that of the double-blind phase. In all groups receiving obeticholic acid there was a low incidence of serious adverse events (19%) and none were considered likely to be related to obeticholic acid. During the OLE, 11% of patients discontinued treatment. Despite pruritus being the most common adverse event, dose titration was shown to help manage it and pruritus was controlled with longer treatment.47 The long-term safety extension is ongoing; data collection ends in 2018.

The POISE study validates the safety and efficacy of obeticholic acid (monotherapy and in combination with UDCA) at an optimal dosage of 5–10 mg/day.7,47 OCALIVA improves markers of cholestasis, hepatic damage, and function: changes that were sustained with treatment of up to 3 years within the study. In the OLE, obeticholic acid was generally well-tolerated with no apparent new safety signals with longer-term treatment.47

Phase IV Study

COBALT is a Phase IV study of obeticholic acid, assessing PBC clinical outcomes of combination therapy with UDCA. This is an ongoing, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study at around 170 sites internationally.48

OBETICHOLIC ACID: REAL-WORLD PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Case study presentations were used to demonstrate the management of PBC in a real-world setting.

Management of Pruritus

Dr Andreas Kremer

Dr Kremer presented the case of a 47-year-old woman with moderate fatigue and mild pruritus with elevated ALP (3.38-fold the ULN). Sonography and a biopsy confirmed PBC. Following 2 years of UDCA treatment, ALT was reduced, but ALP remained elevated at 3.86-fold the ULN and bilirubin had slightly increased. Initiation of obeticholic acid (5 mg/day) led to improvements in liver biochemistry and, following 4 months of treatment, ALP had reduced to 2.30-fold the ULN; however, the patient experienced treatment-emergent pruritus. Pruritus was managed as follows: obeticholic acid treatment was stopped and cholestyramine administered. Cholestyramine had to be discontinued due to lack of efficacy and rifampicin was prescribed, which resulted in pruritus relief. Obeticholic acid was restarted at 5 mg/week, up-titrated every 2 weeks, and after 2 months the patient was on a dose of 5 mg/day. Three months after reinitiating obeticholic acid, the patient exhibited a reduction of ALP to 1.73-fold the ULN and had bilirubin within the normal range.

This case demonstrated how to implement a stepwise approach to pruritus management with a successful outcome of pruritus resolution. The patient benefited from the implementation of second-line obeticholic acid and the efficacy of this treatment was demonstrated by reduction of ALP and bilirubin.

Professor Vincent Leroy

Prof Leroy discussed the management of a woman who was diagnosed with PBC at 53 years old. Her ALP was elevated to 2.6-fold the ULN and she was presenting with fatigue and mild pruritus. Evaluation after 12 months of UDCA treatment showed that her ALP had reduced to 1.9-fold the ULN; however, her bilirubin had increased from 9 µmol/L to 14 µmol/L. It was determined that this patient had an inadequate response to UDCA according to Paris II response criteria.5 The patient had mild-to-moderate pruritus, and for such patients who require second-line therapy it is recommended to manage pruritus prior to treatment initiation.12 This means starting with cholestyramine, which was ineffective in this case, and then rifampicin, which reduced pruritus to a manageable level. The patient was then initiated on obeticholic acid at 5 mg/day and with this dose, pruritus recurred. Obeticholic acid was paused until resolution and subsequently reinitiated at a lower dose of 5 mg three times a week and increased to 5 mg/day at 1 month due to good tolerance. Obeticholic acid was efficacious in this patient; after 9 months ALP declined to 1.3-fold the ULN and bilirubin reduced to 13 µmol/L.

All patients who respond inadequately to UDCA highlight the importance of follow-up and on-treatment assessments to evaluate disease status and inform treatment decisions. Pruritus management prior to obeticholic acid initiation is an optimal scenario as often this can prevent treatment interruption; however, other strategies can be implemented such as obeticholic acid pause or dose modification (to 5 mg three times a week).42

Managing High-Risk Patients

Professor Frederik Nevens

Prof Nevens discussed the case of a 48-year-old male PBC patient whose ALP was 3.41-fold the ULN at presentation and had increased to 3.53-fold the ULN despite 12 months of UDCA. This patient’s sex and biochemical response profile classified him as being at high risk of disease progression; studies also suggested increased likelihood of hepatocellular carcinoma.5,49 Suitable characteristics, including no evidence of decompensated cirrhosis at baseline, meant that he was eligible for enrolment in the POISE trial. The patient was randomised to obeticholic acid at 5 mg/day. After 12 months of treatment, the patient’s ALP had decreased to 1.74-fold the ULN and there were corresponding reductions in bilirubin and TE values. Further follow-up after 4 years of treatment at 10 mg/day showed that these results were sustained, and ALP was 1.62-fold the ULN.

Characteristics such as male sex can classify an individual as at high risk of both disease progression and the development of complications.5 When there is inadequate response or intolerance to UDCA, obeticholic acid therapy, at an appropriate dose, should be considered. As the POISE trial exemplifies, obeticholic acid can improve surrogate markers of disease severity in these patients.5,7,47

Professor Gideon Hirschfield

Prof Hirschfield’s case study was a young (and therefore high-risk) 41-year-old female with Child–Pugh A cirrhosis and portal hypertension, diagnosed with PBC through AMA-positivity, ultrasound, and an ALP of 10.2-fold the ULN. The patient’s 15-year GLOBE score was 21.9% lower than the average of a matched healthy population, which identified an unmet treatment need. Following 12 months of UDCA, the patient displayed an ALP 2.56-fold the ULN and was considered to have an inadequate response. Obeticholic acid was initiated at 5 mg three times a week due to the presence of portal hypertension and, following this, the patient experienced mild pruritus, which was resolved with cholestyramine. Obeticholic acid treatment was considered successful due to improvements in liver function markers at 6 months: ALP (now 1.81-fold the ULN), AST, bilirubin, and platelets.

GLOBE scoring is a useful prognostic tool that considers treatment response and parameters of disease severity.5 Using scoring systems for risk stratification can facilitate PBC management, particularly for patients identified as high risk (for example, those who are young at diagnosis, male, or have advanced disease at presentation).5,8 Furthermore, when second-line treatment is necessary, obeticholic acid can be used to successfully treat patients with compensated cirrhosis, adapting the starting dose as necessary and up-titrating based on tolerability.7,42,47 Maximum recommended dose in patients with Child–Pugh B or C is 10 mg twice weekly.42

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Professor Luigi Muratori

Prof Muratori highlighted some of the important topics that had been discussed, including identifying patients at high risk of disease progression, determining inadequate response to initial therapy, initiating second-line therapy with obeticholic acid (OCALIVA▼), and reducing symptom burden to optimise QoL. He advocated improving collaboration between patients and clinicians, stating that enhanced sharing of information and experience could improve outcomes for patients and increase the standard of PBC care globally.