BACKGROUND AND AIMS

Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy (ICI) has revolutionised cancer care but is associated with immune-related toxicities, which may require ICI discontinuation and immunosuppressive therapies (IST). Severe ICI hepatotoxicity is treated with high-dose corticosteroids; however, 30% of patients may be steroid-refractory (no response after 48–72 hours) or steroid-resistant (rebound alanine aminotransferase [ALT] upon steroid taper).1,2 Further management for these patients is not well defined. The authors sought to better understand management of severe ICI hepatotoxicity and responses to IST.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients receiving ICI in early phase clinical trials at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada, or treated at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease, Ontario, Canada, for ICI hepatotoxicity were included. Patients with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Grade 3 ICI hepatotoxicity (ALT >5 times the upper limit of normal) were identified and clinical records reviewed for management and outcomes. Patients with an alternate cause for ALT elevation, who did not receive corticosteroids, or with HCC or viral hepatitis were excluded.

RESULTS

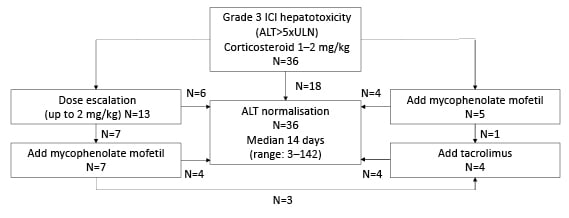

Between August 2012 and December 2021, 36 patients with Grade 3 ICI hepatotoxicity were identified. Most (23; 64%) had metastatic melanoma. Thirteen received anti-CTLA-4/PD-1, 18 received anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1, and five received anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy. All patients initially received corticosteroids (1–2 mg/kg/day prednisone equivalent). Figure 1 shows response to corticosteroids and sequence of additional IST. Eighteen patients (50%) were poor corticosteroid responders, either steroid-refractory (four; 11%) or steroid-resistant (14; 39%). Age, sex, liver metastases, prior ICI exposure, or peak ALT did not predict steroid response, although poor responders were more likely to have been treated with combination anti-CTLA-4/PD-1 (10 [55%] of poor responders versus three [17%] of responders; p=0.04). Thirteen received steroid dose escalation (up to 2 mg/kg/day), with response in eight. Overall, 12 patients (66%) required treatment with mycophenolate (MMF) as second-line IST. Five were transitioned directly to MMF, and seven after failure of steroid escalation. Four (33%; 11% of total cohort) did not respond to MMF and required third-line IST (tacrolimus). Age, sex, liver metastases, prior ICI exposure, or peak ALT did not predict need for second- or third-line IST. ALT normalised in all, after median 14 days (range: 3–142 days). Total time on IST was shorter in steroid responders than poor responders (medians of 45 days [range: 9–177 days] and 104 days [range: 30–371 days], respectively; p<0.01). Amongst patients with poor response to initial corticosteroids, there was no difference in peak ALT or time to normalisation of ALT between patients treated with steroid escalation relative to MMF. The MMF group showed numerical trends towards shorter duration of corticosteroids (medians of 61 days [range: 32–86 days] and 97 days [range: 21–275 days], respectively) and reduced need for additional lines of IST (one patient [20%] versus seven [54%]), although not reaching statistical significance in this small cohort. Steroid-related adverse events occurred in two patients (vertebral fracture; hyperglycaemia); both were poor steroid responders treated with steroid escalation. Over median follow-up of 14.1 months (range: 2.3–81.5 months), 14 patients died. Ten patients were rechallenged with ICI, and none developed recurrent hepatotoxicity. No patients died of complications of hepatotoxicity.

Figure 1: Sequence of treatment with immunosuppressive therapies in patients with severe immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hepatotoxicity.

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; ULN: upper limit of normal.

CONCLUSION

Poor steroid response is common in patients with severe ICI hepatotoxicity. Earlier introduction of second-line IST (MMF) may be associated with equivalent outcomes to steroid escalation and reduce total time on IST. Tacrolimus is effective as third-line therapy, if required. These results will assist development of treatment algorithms for severe ICI hepatotoxicity, for further prospective evaluation.