Meeting Summary

This article details interviews conducted by EMJ in January and February 2023 with two key opinion leaders. Emily Curran is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Hematology and Oncology, at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Ohio, USA. Curran specialises in haematology, medical oncology, and internal medicine, with a clinical interest of the care of patients with haematologic malignancies, particularly acute leukaemia. Matthias Stelljes is a Professor of Medicine in the Department of Medicine, Hematology and Oncology at the University of Münster, Germany. Stelljes is responsible for the adult allogeneic stem cell transplant programme, and has a clinical focus on optimising treatment strategies for patients with high-risk relapsed or refractory (R/R) haematologic malignancies before and after stem cell transplantation, mainly acute leukaemia.

In the interviews, the experts provided their real-world insights and recommendations for therapy management in patients with adult R/R B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), based on their transatlantic experience. They discuss balancing the benefits of treatment with inotuzumab ozogamicin versus the risk of veno-occlusive disease (VOD), otherwise referred to as sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS), and offer strategies for mitigating the risk of VOD/SOS.

INTRODUCTION

The prognosis for adult patients with R/R B-cell ALL can be poor, and treatment can be challenging. The goal of treatment is to achieve remission and control the disease, as well as manage associated symptoms and improve a patient’s quality of life. Stem cell transplantation is a potential curative treatment option for B-cell ALL, yet depends on a patient’s age, overall health, and cancer status.1,2 To proceed to transplant, complete remission is required; however, many patients relapse with current standard of care intensive chemotherapy, meaning few patients (<30%) proceed to transplant after salvage treatment.1,2

Inotuzumab ozogamicin is a single-agent monotherapy antibody drug conjugate indicated for the treatment of adults with R/R cluster of differentiation (CD) 22-positive B-cell precursor ALL.3 For adult patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive R/R B-cell precursor ALL, inotuzumab therapy may be considered after they have failed treatment with at least one tyrosine kinase inhibitor.1-3 According to Curran, in the USA, “inotuzumab treatment is one of the preferred options for managing relapsed and refractory patients with CD22-positive B-cell ALL.”

THERAPY MANAGEMENT OF B-CELL PRECURSOR ACUTE LYMPHOBLASTIC LEUKAEMIA WITH INOTUZUMAB OZOGAMICIN

The safety and efficacy of inotuzumab for R/R CD22-positive B-cell ALL was evaluated in the global INO-VATE ALL Phase III clinical trial.1,2 This was an open-label randomised study (1:1 to either inotuzumab [up to six cycles] or standard chemotherapy [up to two-to-four cycles, depending on the regimen]) conducted between 2012–2017.1,2 The trial included adults over 18 years with Philadelphia chromosome-positive and -negative R/R CD22-positive B-cell ALL (N=326) with ≥5% bone marrow blasts, and who had received up to two induction chemotherapy regimens.

The co-primary endpoints of the trial included complete remission (CR) including CR with incomplete haematologic recovery of peripheral blood counts (CRi), in the first 218 intent-to-treat population; and overall survival for the full cohort thereafter.1 Long-term follow-up was conducted to explore remission analysis and overall survival analysis, involving 326 patients, with 164 in the inotuzumab group and 162 in the standard chemotherapy group.2

The primary trial analysis (n=218) indicated superiority as a first or second salvage treatment with a CR/CRi of 80.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 72.1–87.7; n=88/109) for inotuzumab, more than doubling the rates compared with 29.4% (95% CI: 21.0–38.8; n=32/109) for standard chemotherapy (p<0.001).1 The long-term follow-up (n=326) indicated that a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved CR/CRi in the inotuzumab group, with 73.8% (n=121/164) compared with 30.9% (n=50/162) for standard chemotherapy (one-sided p<0.0001).2

Median overall survival for inotuzumab was 7.7 months (n=164; 95% CI: 6.0–9.2) compared with 6.7 months for standard chemotherapy (n=162; 95% CI: 4.9–8.3).1 Overall survival hazard ratio was 0.77 (97.5% CI: 0.58–1.03; two-sided p=0.04), where significance was not met at the prespecified boundary of p=0.0208.1 Stelljes acknowledged that the primary endpoint of overall survival was not reached. He noted that in the long-term follow-up, the 2- and 3-year overall survival rates were 22.8% (95% CI: 16.7–29.6) and 20.3% (95% CI: 14.4–27.0), respectively, with inotuzumab, and 10% (95% CI: 5.7–15.5) and 6.5% (95% CI: 2.9–12.3), respectively, with standard chemotherapy.2

Curran discussed that in the USA, inotuzumab is seen as a highly effective treatment in the relapsed and refractory setting, with response rates at around 80%. Curran stated that, in her experience, this was “particularly useful for patients that have a high disease burden, which many patients do,” weighing up the benefits of inotuzumab. However, due to the short-lived remission duration (for patients achieving CR/CRi, median duration of remission was 5.4 months with inotuzumab compared with 4.2 months with standard chemotherapy),2 it is often used as a bridge to transplant or additional therapy.

Stelljes noted that from a European transplanter’s perspective, the goal in salvage therapy is to achieve complete remission and proceed to transplant. He commented: “I would use inotuzumab in nearly all patients [i.e., applies for patients proceeding or not proceeding to transplant] with no contraindications.” Stelljes also emphasised the convenience of using inotuzumab in an outpatient setting.

SAFETY PROFILE OF INOTUZUMAB OZOGAMICIN AND THE SEVERITY OF VENO-OCCLUSIVE DISEASE/SINUSOIDAL OBSTRUCTIVE SYNDROME

Findings from the INO-VATE trial identified that the most common, clinically important, serious adverse events reported for inotuzumab were infection, febrile neutropenia, haemorrhage, abdominal pain, pyrexia, VOD/SOS, and fatigue.4 Curran noted that the shorter duration of remission associated with inotuzumab is a consideration when deciding to use inotuzumab, due to the potential associated toxicity, and recommends carefully reviewing who is an appropriate candidate for treatment. Curran also recommended closely monitoring patients for adverse events, particularly VOD/SOS, when administering inotuzumab.

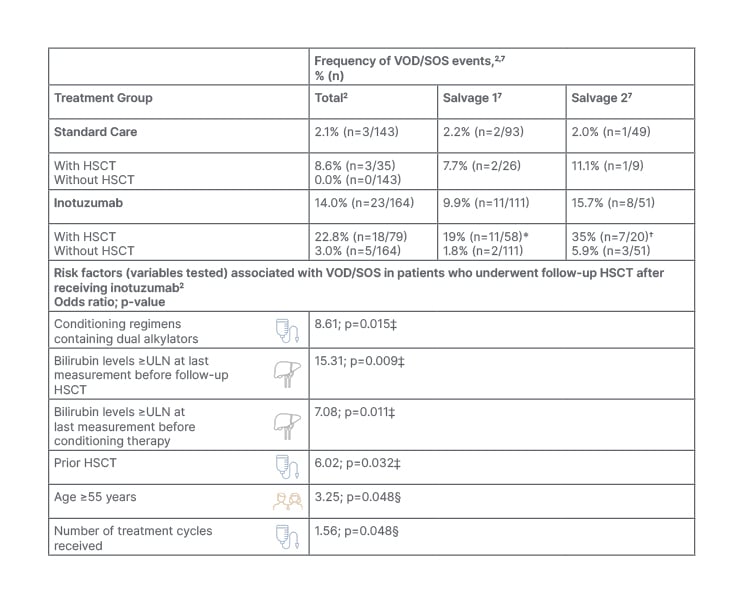

The INO-VATE trial reported an increased risk of VOD/SOS with inotuzumab above that with standard chemotherapy regimens in patients with R/R ALL, with an incidence of 14% (n=23/164) reported in the inotuzumab group, compared with 2% (n=3/143) for standard chemotherapy (Table 1).2,4

Table 1: Risk factors for the development of veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction symdrome (VOD/SOS) in patients treated with inotuzumab.2,4,7,10

*Including 3% Grade 1–2, 9% Grade 3–4, and 7% Grade 5.

†Including 5% Grade 1–2, 25% Grade 3–4, and 5% Grade 5.

‡Multivariate analysis of associated risk of VOD/SOS.

§Univariate analysis of associated risk of VOD/SOS.

HSCT: haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; SOS: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; ULN: upper limit of normal; VOD: veno-occlusive disease.

VOD/SOS is a severe, life-threatening hepatic complication that can occur following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).5 Both Curran and Stelljes highlighted that the greatest risk of VOD/SOS occurred in patients who underwent HSCT. Stelljes noted that the risk of VOD/SOS development following salvage with inotuzumab was not high in those not proceeding to HSCT (3.0%; n=5/164).2 However, within the group of patients who received allogeneic HSCT following inotuzumab treatment in the INO-VATE trial (n=79/164), VOD/SOS was reported in 23% (n=18/79).2 The incidence was lower when inotuzumab was used in the first salvage line compared with the second salvage line (19% versus 35%, respectively; Table 1).4,6,7 Of note, a lower proportion of patients proceeded to HSCT following the standard chemotherapy (n=36/162), and the post-HSCT VOD/SOS rate was 7.7% (n=2/26) in the first salvage, and 11.1% (n=1/9) for the second salvage.2,7

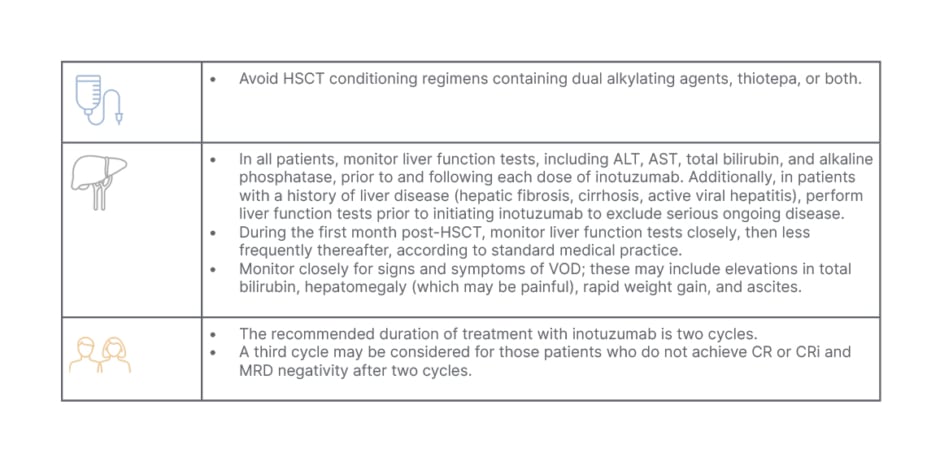

The incidence of VOD/SOS in those patients who received inotuzumab treatment but did not undergo subsequent HSCT was lower (3.1% overall), at 1.8% (n=2/111) in the first salvage line (both cases Grade 3–4) and 5.9% in the second salvage (n=3/51; 2% Grade 1–2, and 4% Grade 3–5).4,6,7 It should be noted that, due to the small sample size, results should be interpreted with caution, and additionally, some patients may not have developed VOD/SOS at the time of the analysis, where VOD/SOS can occur up to about 8 weeks following the last treatment dose.4 Stelljes added that the median onset of VOD/SOS after HSCT in INO-VATE was 15 days, ranging from 3 to 57 days. He emphasised the importance of monitoring closely for VOD/SOS in the first month post-HSCT, then less frequently thereafter, according to standard medical practice.4 Contraindications include hypersensitivity to the active substance, patients with a history of confirmed severe or ongoing VOD/SOS, and patients with serious ongoing hepatic disease (e.g., cirrhosis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, or active hepatitis).4

HIGH-RISK PATIENT POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS FOR VENO-OCCLUSIVE DISEASE/SINUSOIDAL OBSTRUCTIVE SYNDROME

Both Curran and Stelljes outlined that the incidence and severity of VOD/SOS following HSCT were associated with baseline transplant characteristics, including prior HSCT status and conditioning regimens containing dual alkylators.2 Additionally, the risk increases when patients receive a second allogeneic transplant after relapse to the first (Table 1).5 The frequency of VOD/SOS following HSCT in INO-VATE was greatest in those patients with a pre-trial HSCT (45% [n=5/11; 95% CI: 16.7–76.6]; 45% Grade 3–5, and 18% Grade 5) compared with 18% in those who had not had a prior HSCT (n=12/66; 95% CI: 9.8–29.6).6 Additionally, the frequency was higher in those who had previously received a dual alkylator conditioning regimen (55% [n=6/11; 95% CI: 23.4–83.3]; 55% Grade 3–5, and 18% Grade 5), compared with 15% for those who had received just a single alkylating agent (n=8/52 [95% CI: 6.9–28.1]).6 Stelljes pointed out that, in Europe, the current standard for conditioning therapy consists of total body irradiation-based regimens (fractionated dose of 8–12 Gray), and typically does not involve dual alkylators, which can help to mitigate the risk of VOD/SOS.

Curran added that VOD/SOS was higher in those who received more cycles of inotuzumab prior to transplant. Stelljes explained that two cycles is the standard for those proceeding to transplant. He stated that this “is important to avoid further toxicity and increasing the risk of VOD.” An increased risk was seen after four-to-six treatment cycles in INO-VATE in those who proceeded to HSCT (42% [n=5/12; 95% CI: 15.2–72.3]; 8% Grade 1–2, 25% Grade 3–4, and 8% Grade 5), compared with just 8% after one treatment cycle (n=1/12; 95% CI: 0.2–38.5), 19% (n=5/27; 95% CI: 6.3–38.1) after two treatment cycles, and 23% (n=6/26; 95% CI: 9.0–43.6) after three treatment cycles, where no patient achieved CR after three cycles.6 Therefore, by using this approach as a bridge to HSCT, efficacy is not compromised.

Curran supported this, saying the practice of limiting treatment to two cycles of inotuzumab in prospective transplant patients has been frequently adopted in the USA, citing real-world evidence from a multicentre cohort analysis from the USA.8 This analysis found that the median number of cycles provided was two, with a range between one and six.8

Stelljes also outlined real-world evidence from a UK multicentre, retrospective chart review, in which those patients who proceeded to HSCT received a median of two cycles of inotuzumab.9 Of those who did not proceed to HSCT, the number of cycles ranged from one to six, with a median of three cycles.9 The response rates, overall survival, and safety profile were also consistent with the Phase III INO-VATE study.

From a practitioner’s perspective, Curran indicated that for R/R patients proceeding to transplant, inotuzumab should be limited to two cycles, and the conditioning regimen should avoid dual alkylating agents. The Summary of Product Characteristics for inotuzumab recommends two treatment cycles for those proceeding to transplant, where a third cycle may be considered for those who do not achieve CR/CRi and minimal residual disease negativity status within two cycles.3,4 For those not proceeding to transplant, up to six cycles can be used.4 Furthermore, Curran stressed the importance of considering additional risk factors when determining the number of treatment cycles.

Stelljes outlined that there are several patient risk factors associated with an increased risk of VOD/SOS, such as elevated liver enzymes, elevated transaminases, and a history of liver disease (e.g., pre-existing hepatitis, viral hepatitis, or severe liver toxicity). In the INO-VATE trial, those patients in the inotuzumab group with a history of liver disease who proceeded to HSCT, the incidence of VOD/SOS was 35% (n=7/20; 95% CI: 15.4–59.2) compared with 18% in those without (n=10/57; 95% CI: 8.7–29.9).6 Furthermore, elevated bilirubin levels (≥upper limit of normal) prior to HSCT was associated with 58% (n=7/12; 95% CI: 27.7–84.8) incidence of VOD/SOS compared with 15% (n=10/65 ; 95% CI: 7.6–26.5) in those with normal liver function (<upper limit of normal).6 However, Stelljes said: “These risks do not always preclude the use of inotuzumab as a salvage therapy,” but pointed out that in those with serious ongoing hepatic disease, inotuzumab is contraindicated.

Both experts agreed that in their daily practice, besides pre-existing liver disease, liver cirrhosis, or fibrosis, which would exclude the use of inotuzumab and HSCT,3,4,10 there are a number of factors to consider when contemplating inotuzumab as a treatment option (Table 2). Curran commented that when treating a patient with R/R disease, she would carefully weigh up the benefit-to-risk ratio of inotuzumab compared with other treatment options.

Table 2: Recommendations and treatment considerations for patients proceeding to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.4,10

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CR: complete remission; CRi: complete remission with incomplete haematologic recovery of peripheral blood counts; HSCT: haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MRD: minimal residual disease; VOD: veno-occlusive disease.

An increased frequency of VOD/SOS was also associated with older adults (aged ≥65 years).4 In the INO-VATE trial, among patients aged ≥65 years in those proceeding to HSCT, the incidence of VOD/SOS was 50% (n=3/6; 95% CI: 11.8–88.2) compared with 20% (n=14/71; 95% CI: 11.2–30.9) in those <65 years (note that the results should be cautiously interpreted due to the very small sample size).6 Univariate analysis indicated that for those who were aged ≥55 years old proceeding to HSCT, the incidence of VOD/SOS was 41% (n=7/17; 95% CI: 18.4–67.1) compared with 17% (n=10/60; 95% CI: 8.3–28.5) in those <55 years old.6 However, Curran suggested that this should not be a major cause for concern, stating: “Often, older patients may not be suitable candidates for transplant. While there may be a higher risk in the older age group, since they are not going to be undergoing transplantation, the overall risk is balanced out.”

MITIGATING THE RISKS OF VENO-OCCLUSIVE DISEASE (VOD/SOS)

Most cases of VOD/SOS are mild-to-moderate, and can resolve progressively within a few weeks, but very severe cases can lead to multi-organ dysfunction and high mortality.5 Early detection and treatment may help prevent the most severe cases, which are a known risk associated with HSCT, yet can also occur in the absence of HSCT.5,10-12 The development of VOD/SOS is often rapid and unpredictable, emphasising the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors to aid prompt diagnosis and early treatment.5 Risk mitigation strategies tailored to each patient can reduce the risk of VOD/SOS.4,5,10,12

Stelljes emphasised the need for experienced clinicians to exchange information and data about the risk of VOD/SOS at the beginning of treatment. He stated that it is essential to be informed about “risk factors and the consequences of these therapies for some patients,” deciding when to employ certain conditioning regimens, and when to avoid certain drug therapies, as well as “finding the best for patients, and to consider other treatment options as a salvage therapy for those who are at higher risk of VOD.”

Criteria from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) have outlined several modifiable risk factors, such as the conditioning regimen, and unmodifiable risk factors such as older age, pre-existing liver cirrhosis, or liver fibrosis.4,5,12 Best practice recommends a comprehensive risk assessment, which should include both modifiable and unmodifiable factors, including donor type (or human leukocyte antigen-matching), conditioning regimen, and whether a second allogeneic HSCT is used.5,12 In addition, factors such as older age, as well as hepatic-related risk factors, including hepatic dysfunction (including serum bilirubin levels above 1.5 mg/L), or pre-existing liver diseases, should also be considered.5,12 This will help identify those who are most at risk of developing severe VOD/SOS.5,11,12 Careful monitoring is recommended to detect probable, clinical, and proven VOD. Furthermore, it is important to identify non-classical, late-onset presentations.5,11,12

Curran indicated that the EBMT criteria can be useful to identify and prevent toxicities, such as infection-related signs and symptoms, as well as VOD/SOS. She also highlighted the importance of monitoring patients closely for toxicities post-HSCT.4,10 Additionally, Curran highlighted that the risk is based on the conditioning regimen used, or other factors associated with a higher risk of VOD/SOS; thus, it is important to be aware of the conditioning regimen to avoid overlapping toxicities. She noted that it is not necessarily differences in the patient population, but the combination of the transplant and the conditioning regimen that creates the highest risk of toxicity.

MONITORING AND DIAGNOSIS OF VENO-OCCLUSIVE DISEASE (VOD/SOS)

A key recommendation for managing VOD/SOS risk is to closely monitor all patients, particularly those who have undergone HSCT, for signs and symptoms of VOD/SOS.5,10,11 The main symptoms of VOD/SOS include painful hepatomegaly, body weight gain, ascites, elevated bilirubin levels, transfusion refractory thrombocytopenia, jaundice, and, in severe cases, multi-organ damage.5

Stelljes indicated that diagnosing VOD/SOS can be challenging due to its dynamic manifestation; however, the EBMT guidelines provide criteria to improve diagnosis and facilitate timely intervention.5,11,12 As of April 2023, the EBMT guidelines have been refined to improve the identification and prevention of modifiable risk factors.5 Moreover, the guidelines emphasise earlier diagnosis of probable/clinical/proven VOD/SOS, and treatment to improve the management of VOD/SOS and enhance patient outcomes.5 Curran and Stelljes both recommended monitoring bilirubin levels as the best approach, and checking for other signs of VOD/SOS, such as weight gain and increased transaminase levels according to the EBMT criteria.5,11,12 The EBMT has also developed a severity grading system for VOD/SOS, ranging from mild to very severe based on various criteria, including time since first clinical symptoms, bilirubin and transaminases levels, body weight, renal function, and other signs of multi-organ dysfunction.5,12 The EBMT diagnostic and severity grading criteria should be used when VOD/SOS is suspected. This is to facilitate appropriate treatment and prompt initiation due to the high risk of mortality in severe and very severe VOD/SOS.5,11,12 Elastography to measure liver stiffness and ultrasound can assist in differential diagnosis, and confirm clinical findings.5

Stelljes summarised that screening for VOD/SOS should include the usual laboratory testing, liver ultrasound, and patient history. However, differentiating the onset of VOD/SOS from hepatotoxicity is very difficult, particularly during the first phase after transplant. Stelljes also noted that severe infections such as septicaemia, or sepsis caused by Gram-negative bacteria, can produce the same clinical symptoms as VOD/SOS. Therefore, monitoring graft-versus-host disease and anti-thymocyte globulin antibodies is important. In severe cases, treatment with defibrotide may be warranted.5,12,13

Curran agreed that the history of liver disease and bilirubin levels are the predominant risk factors, along with elevated liver function tests, although this may differ between institutions. However, she raised the point that the EBMT criteria may be useful for post-transplant situations, but how they apply to non- or pre-transplant settings is less clear.11 Curran stated that, in the pre-transplant setting, there are no specific criteria dictating clinical practice, although the EBMT criteria and the inotuzumab Summary of Product Characteristics3 provide useful guidance for decision-making.

Stelljes outlined that prior to transplant, in the first salvage cycle of inotuzumab, liver enzymes and blood work-up tests should be checked two to three times a week, especially in higher-risk patients. After transplant, signs of VOD/SOS should be observed every day during the first month, including liver enzymes, bilirubin, weight increases, renal function checks, and patient examination; and then with reducing frequency according to the patient’s progress.4

MULTIDISCIPLINARY MONITORING OF VENO-OCCLUSIVE DISEASE (VOD/SOS)

Curran highlighted the crucial role of a multidisciplinary team in monitoring and mitigating against VOD/SOS. This involves regular checks by physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and transplant specialists, all of whom should be trained to identify the signs and symptoms of VOD/SOS and risk factors, such as prior chemotherapy. The care team should be alert to signs of VOD/SOS in all patients, but particularly post-transplant patients with older age and other risk factors, and use lower thresholds of markers such as bilirubin and transaminases levels to trigger, for example, a nurse to inform the physicians or transplant specialists.

Curran emphasised that communication with the transplant physician is essential, particularly in the R/R ALL space, and patient pathways should be discussed early in the treatment process. Curran stated that “communication and education with the transplant physician is really important,” adding, “there is a limited amount of time to get a patient to transplant generally, and so I involve the transplanter before even giving the first dose of inotuzumab.” The need for early communication with the transplant physician to plan for high-risk conditioning and potential side effects was also emphasised, with risk assessment conducted on all patients, and communicated to the multidisciplinary team. To promote vigilance among the team and improve outcomes for VOD/SOS patients, protocols for risk assessment and monitoring should be established, regardless of risk stratification. Due to the short remission period for most patients with B-cell ALL, clear communication between the oncologist/haematologist and transplant specialist from the beginning is necessary to ensure appropriate conditioning and prompt transplant for eligible patients.

Stelljes also emphasised the importance of planning for transplant early on, especially for patients who are typically young and fit enough for an allogeneic stem cell transplant, and are starting salvage treatment with inotuzumab. Waiting for a donor search and contacting the transplant centre during the second or third cycle is not advisable, according to Stelljes. He explained that in Germany, the clinical team collaboratively checks the laboratory values of patients, including liver enzymes, bilirubin, kidney function, and weight increase, to monitor for signs of VOD/SOS. Stelljes highlighted the crucial role of nurses in monitoring for signs of VOD/SOS, such as twice-daily weight checks, abdomen circumference measurements, and ultrasound monitoring in the standard settings, and reporting any concerns directly to the clinicians.

SUMMARY

Outcomes in patients with R/R ALL are poor. Achieving remission and successfully proceeding to allogeneic HSCT provides the greatest chance of long-term survival. Inotuzumab is a valuable option for salvage treatment, with a recommended two cycles of treatment for prospective transplant patients to reduce toxicity risk, as per the label. VOD/SOS can occur and can be severe; therefore, patient fitness and comfort should be taken into consideration, while remaining vigilant for the risk of VOD/SOS and monitoring to allow early detection if it does arise, so that intervention can be implemented when necessary.

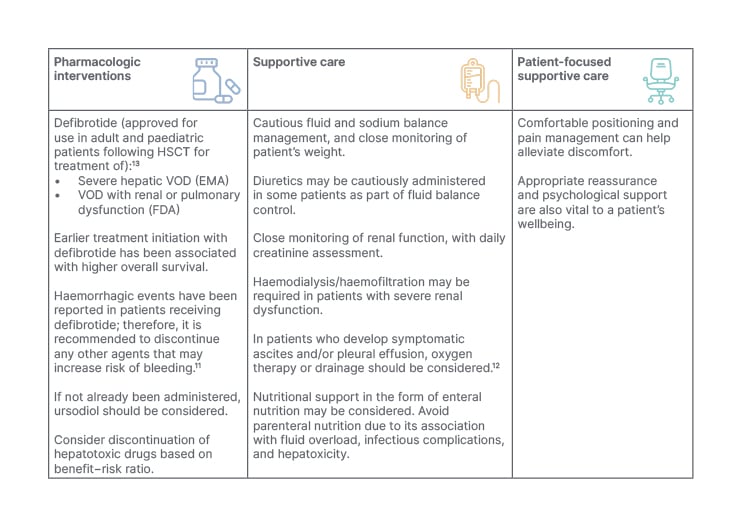

A recommendation for healthcare professionals is to be aware of the possibility of late-onset VOD/SOS and other non-classical presentations,5,12 and to carefully monitor patients for signs and symptoms of VOD/SOS, especially after HSCT. To facilitate diagnosis and prompt treatment, it is advised to use the EBMT severity grading criteria, particularly for patients at higher risk of VOD/SOS. Because severe/very severe VOD/SOS has a high risk of mortality, it is mandatory to start treatment promptly, with defibrotide being initiated as soon as possible.13 Healthcare professionals should also consider implementing appropriate supportive care measures (Table 3).

Table 3: European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation recommendations for veno-occlusive disease (VOD/SOS) treatment and management.5,12

EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HSCT: haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; VOD: veno-occlusive disease.

Prescribing information for Pfizer products mentioned in this article: Besponsa™▼ (inotuzumab ozogamicin) can be found here for Great Britain and here for Northern Ireland.

Compliance number: PP-INO-GBR-0907

December 2023

References

- Kantarjian HM et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740-53.

- Kantarjian HM et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard of care in relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: final report and long-term survival follow-up from the randomized, phase 3 INO-VATE study. Cancer. 2019;125(14):2474-87.

- Pfizer. BESPONSA, INN-inotuzumab ozogamicin: summary of product characteristics. 2022. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/besponsa-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Last accessed: 2 March 2023.

- Pfizer. BESPONSA, Highlights of prescribing information. 2018. Available at: https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=9503. Last accessed: 28 July 2023.

- Mohty M et al. Diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a refined classification from the European society for blood and marrow transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023;58(7):749-54.

- Kantarjian HM et al. Hepatic adverse event profile of inotuzumab ozogamicin in adult patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results from the open-label, randomised, phase 3 INO-VATE study. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(8):e387-98.

- Jabbour E et al. Impact of salvage treatment phase on inotuzumab ozogamicin treatment for relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an update from the INO-VATE final study database. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(8):2012-15.

- Badar T et al. Real-world outcomes of adult B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with inotuzumab ozogamicin. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(8):556-60.e2.

- Marks DI et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin in relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a real world retrospective study in the UK. Abstract EP371. EHA 2021, 9 June, 2021.

- Kebriaei P et al. Management of important adverse events associated with inotuzumab ozogamicin: expert panel review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018;53(4):449-56.

- Mohty M et al. Revised diagnosis and severity criteria for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a new classification from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(7):906-12.

- Mohty M et al. Prophylactic, preemptive, and curative treatment for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a position statement from an international expert group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(3):485-95.

- Jazz Pharmaceuticals. DEFITELIO (defibrotide sodium), summary of product characteristics. 2022. Available at: https://pp.jazzpharma.com/pi/defitelio.gb.SPC.pdf Last accessed: 28 July 2023.