BACKGROUND AND AIMS

In 2020, three somatic mutations in the X-linked gene UBA1, coding for an essential ubiquitin activating enzyme, were reported to cause VEXAS syndrome, a novel haemato-inflammatory disease that manifests with both cytopenias and autoinflammation.1 The mutations alter the start codon (M41) of the cytoplasmic isoform of UBA1, resulting in the cytoplasmic-only loss of function of UBA1. Approximately 50% of patients with VEXAS develop myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but interestingly progression to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is extremely rare. The speculated protective mechanisms of UBA1 mutations from malignant transformation intrigued the authors to retrospectively analyse the whole genome data from more than 4,000 patients diagnosed with various haematological malignancies (HM), which revealed 16 putative somatic non-M41 UBA1 variants.2 Most of the novel mutations surrounded either adenosine triphosphate-contacting, ubiquitin-contacting, or interdomain-interacting residues, which are considered to affect both the nuclear and cytoplasmic isoforms of UBA1. Surprisingly, secondary AML progression was not rare in patients harbouring the novel non-M41 UBA1 variants. Literature indicates involvement of UBA1 in DNA damage repair,3 which suggested mutations impairing UBA1 nuclear isoform may be more malignant than M41 variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To further understand this difference, Munich Leukemia Laboratory (MLL), Germany, introduced the entire coding sequence of UBA1 in the gene panel for 9,771 samples sent for diagnostic testing. The somatic state of the variants were assigned based on the variant allele frequency as previously described,2 and the variants were further classified into priority variants, if they had been previously detected in symptomatic patients2,4,5 and surrounded the functional residues.6 All other variants were classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

RESULTS

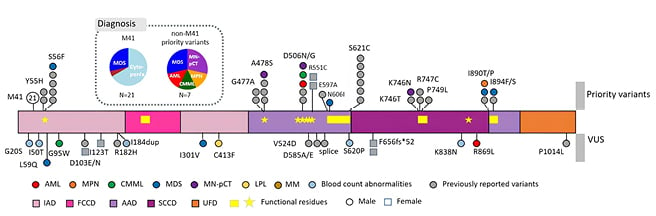

In this new screen, the authors detected 28 UBA1 variants in 42 patients (Figure 1). M41 variants were detected in 21 patients, non-M41 priority variants in seven patients, and non-M41 VUS in 15 patients (nine males; six females), including five patients with multiple mutations. All priority variants were detected in male patients.

Figure 1: Detected UBA1 variants and associated diagnoses.

Loci of variants are shown as circles on the genes, with their diagnoses colour coded. Loci of previously reported variants are shown in grey to denote recurrence. Known functional regions are highlighted by yellow within the gene. Females are denoted by squares.

AAD: active adenylation domains; AML: acute myeloid leukaemia; CMML: chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia; FCCD: first catalytic cysteine half-domain; IAD: inactive adenylation domains; LPL: lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; MM: multiple myeloma; MN-pCT: myeloid neoplasm post cytotoxic therapy; MPN: myeloproliferative neoplasm; SCCD: second catalytic cysteine half-domain; UFD: ubiquitin fold domain; VUS: variants of uncertain significance.

Concerning diagnosis, M41 variants were detected only in patients diagnosed with MDS (N=6) or with suspected MDS (N=14), with one multiple myeloma exception. In contrast, the priority variants were again detected in patients diagnosed with more aggressive HMs (two MDS; one chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia; one myeloproliferative neoplasm; one AML; and two myeloid neoplasms post cytotoxic therapy), three of whom showed more than 10% blasts. The non-M41 VUS also received diverse diagnoses. The patients carrying the M41 variants infrequently carried co-mutations (29%) or cytogenetic aberrations (5%), whereas the male non-M41 variants often harboured co-mutations (67%) and cytogenetic aberrations (33%).

Presence of inflammatory symptoms was not required to be included in the screening, but records of inflammatory symptoms were communicated for nine out of 21 patients harbouring M41 variants. Two out of 7 patients carrying priority variants had cutaneous vasculitis, and one patient carrying a VUS (L59Q) was suspected to have sweet syndrome.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the ongoing large-scale screen of non-M41 variants in patients suspected of HMs continues to detect both recurrent and novel non-M41 variants. The patients harbouring non-M41 variants are rare but may be more malignant, and functional validation would contribute to clarifying the role of UBA1 in haematology and its prognostic significance.