Abstract

Background: The older inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population is challenging to treat because of heterogeneity in characteristics related to frailty. The authors aimed to study factors contributing to the difference in treatment between older and younger patients with IBD and the relation between frailty and therapy goals, from the perspectives of both professionals and patients with IBD.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews in 15 IBD professionals and 15 IBD patients aged ≥65 years.

Results: Professionals had 1–20 years of experience, and three practiced in an academic hospital. Patients were aged 67–94 years and had a disease duration between 2 years and 62 years. The authors found that professionals aimed more often for clinical remission and less often for endoscopic remission in older compared with younger patients. Older patients also aimed for clinical remission, but valued objective confirmation of remission as a reassurance. Professionals sometimes opted for surgery earlier in the treatment course, while older patients aimed to prevent surgery. Professionals’ opinion on corticosteroids in older patients differed, while patients preferred to avoid corticosteroids. In professionals and patients, there was a shift towards goals related to frailty in patients with frailty. However, professionals did not assess frailty systematically, but judged frailty status by applying a clinical view.

Conclusions: Many therapy goals differed between older and younger patients, in both professionals and patients. Professionals did not assess frailty systematically, yet aspects of frailty influenced therapy goals. This underlines the need for clinically applicable evidence on frailty in IBD, which could aid tailored treatment.

Key Points

1. Inflammatory bowel diseases, consisting of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, have an increasing prevalence worldwide, particularly in the older population.2. Treatment for this older patient cohort can be difficult, owing to the group’s marked diversity in areas such as function, mental capacity, and frailty.

3. The authors studied the differences in treatment which often occur between older and younger patient populations, and the relationship between frailty and therapy goals, using perspectives of both patients and professionals.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are chronic diseases occurring as a relapsing and remitting inflammation of the intestines. Patients experience disabling symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and fatigue.1,2 The prevalence and incidence of IBD is increasing, especially in the older patient population.3,4 IBD treatment is often challenging in older patients because this population is heterogenous in their functional, mental, and social capacities, and sometimes live with frailty.5,6 Moreover, it has been established that older patients with IBD are often undertreated compared with younger patients.⁷ Corticosteroids are only suitable for remission induction and not for maintenance therapy due to their unfavorable safety profile.8-12 However, longer courses of corticosteroids are prescribed to older patients and step-up towards maintenance therapy, such as immunomodulators or biologicals, is less frequently initiated.7-13 This difference in pharmacologic treatment between older and younger patients is not necessarily because of a milder disease course in older patients.7

Guidelines do not differ between older patients aged ≥65 years versus younger patients with IBD. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) advises gastroenterologists to assess an individual’s frailty when making treatment decisions in older patients.14 Meanwhile, evidence on the prevalence of frailty and the role of frailty in treatment safety and effectiveness in older patients with IBD is scarce.15-18 It is unclear which patient characteristics are deemed important by professionals and patients in the management of IBD in older patients, and which therapy goals are currently being pursued. Furthermore, it is unclear if and how frailty is accounted for in current clinical practice.

In this article, the authors aimed to study factors contributing to the difference in treatment between older and younger patients with IBD and the relation between frailty and therapy goals, from the perspectives of both professionals and IBD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a semi-structured interview study consisting of 34 face-to-face, in-depth interviews with professionals and patients. The study is reported following the checklist of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)¹⁹ and was conducted in two parts. Initially, professionals were interviewed between May and July 2019. Next, older patients with IBD were interviewed between June and October 2020.

Participants

Professionals

Professionals were defined as either gastroenterologists with a focus on IBD or nurses specialised in the treatment of IBD working in the Netherlands. Professionals were approached for inclusion by email. Purposive sampling was applied to ensure a heterogeneous population,20 and professionals were included based on differences in age, sex, geographical location of practice, nature of hospital of practice (referral versus general hospital), and possession of a PhD title. Professionals were included after signing informed consent and agreeing to having the interview audio taped. The authors aimed to include at least 15 professionals (10 gastroenterologists and five IBD nurses).

Patients

Patients were recruited at the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), the Netherlands, and were eligible if they had a confirmed clinical, endoscopic, and/or histological diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or IBD unclassified. Patients were approached for participation using a letter written on behalf of their treating physician. The authors aimed to include 15 patients aged ≥65 years. To ensure a heterogenous population, purposive sampling was applied by selecting older patients from the authors’ cohort study on geriatric assessment in older patients with IBD.21 In this way, the authors could select patients based on information in the electronical medical record, such as age, sex, IBD disease history, disease duration, IBD medication, and place of living, and based on frailty, comorbidity, and educational level. All patients were included after signing informed consent and agreeing to having the interview audio taped.

In addition, to explore if new themes were generated, the authors aimed to interview five younger patients aged 18–65 years with IBD.

Data collection and setting

Interviews were conducted face-to-face and consisted of two parts. In Part A, the authors conducted a semi-structured interview. In Part B, the interviewer presented prewritten cards. The interviews with professionals were conducted at their workplace, and interviews with patients were performed at their location of preference (hospital or at home). A caregiver or family member was allowed to be present during the patient interviews, and to participate in the interview. Interviews were conducted by two female Master of Medicine students who both had completed their clinical rounds (professionals were interviewed by SW, patients by CV). The interviewers did not know the professionals or patients beforehand, and the interviewers introduced themselves by providing the above information prior to the interview. Both interviewers conducted three practice interviews. Field notes were made during and after each interview. During interviews with professionals and patients, the authors performed interim analyses. Consultation was also performed with members of the research team. No repeat interviews were carried out.

Part A was conducted according to a predefined interview scheme with open-ended questions, and a list of potential additional questions to create more in-depth responses. The interview scheme was developed by the research team (VA, AP, SM, and PM). At the start of the interview, the interviewer introduced herself and collected information about the participant’s baseline characteristics.

In Part B, the authors presented two sets of cards to the participants. First, the interviewer presented a series of cards that each depicted one specific patient characteristic, such as characteristics regarding disease activity and frailty. Professionals and patients were asked to create a hierarchy from most to least important in making treatment decisions in older patients with IBD. Participants were then presented with a series of cards that each featured one specific therapy goal regarding older patients with IBD, such as measures of disease control and preservation of functional status. For both the patient characteristics and therapy goals, participants were allowed to place more than one card in the same hierarchy level. Next, the authors asked professionals if their hierarchy of patient characteristics and therapy goals would be different if applied to younger patients. Finally, both professionals and patients were asked if and how impairments regarding each of the six geriatric characteristics would change the hierarchy of the therapy goals. In each interview, the authors also presented some empty cards to allow participants to add patient characteristics or therapy goals to the list.

In addition, the authors asked professionals if they were reticent in prescribing certain IBD medications in older patients. Initially, only an open-ended question regarding this topic was asked. However, after having performed six interviews, the authors added questions about specific medications. This was either because opinions on these medications (corticosteroids and methotrexate) differed, or because the authors were specifically interested in recently approved medications for IBD care (tofacitinib). Further, after having completed the interviews with professionals, the authors found that there was a difference in the therapy goals and treatment strategies considered to be applied to older patients compared with younger patients. Therefore, a question was added to the patient interviews that highlighted this finding and asked patients for their opinion on it. Moreover, patients were asked about characteristics of frailty. However, after having performed four interviews, the authors noted that this question was hard to answer, and consequently made it more personal by asking: “Do you think that you are frail at the moment?”, “Why do you or do you not think you are frail at the moment?”, and “What would make you (more/less) frail?” Furthermore, the authors added some additional cards in the interviews with patients. After three practice interviews, “Worries about family or loved ones” was added to the set of cards on patient characteristics, and “Decrease in inflammation in the blood ([C-reactive protein] CRP)” was added to the set of cards on therapy goals. After seven interviews, the authors added “Inflammation in the stool ([faecal calprotectin] FCP)” to the former set of the cards. When no new ideas or themes emerged in three successive interviews, the authors concluded that data saturation had been reached.

Data Analyses

All interviews were transcribed verbatim using Amberscript software (Amberscript, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), and transcripts were not returned to participants. The data from Part A were analysed based on the grounded theory approach.²² Two coders coded each interview independently. VA and SW coded the interviews with professionals; VA and CV coded the patient interviews. The two coders frequently met during the coding process to compare codes until consensus was reached. Open coding was performed, and a code list was developed inductively. Codes were renamed and reordered in Excel whenever the coders agreed this was necessary. The code list was used for all subsequent interviews in the same sample of interviewees. In parallel to open coding, axial coding took place, in which the coders performed classification of the codes into categories and themes. This categorisation was completed and revised whenever necessary during and after the interview rounds. To apply structure to the themes that were found, selective coding was applied, and themes were categorised into disease-related (such as IBD symptoms or IBD complications); treatment-related (such as IBD medication or surgery); and geriatric themes, related to daily functioning (such as functional or cognitive status).

The data from Part B were analysed by listing the hierarchy of cards provided by each participant in a separate Excel file. During the analysis, the authors focused on each participant’s top three; most participants included more than one card per hierarchy level. These were analysed independently by the same two coders as in Part A (VA and SW, and VA and CV, respectively). During the analysis, both coders read the considerations that the participants mentioned while ordering the cards, and listed them per card. To create order and to enhance the ability to recognise patterns between different participants, the authors categorised the cards and applied colours to each category. In patients, the authors looked at whether the presence of geriatric impairments, found during a geriatric assessment, seemed associated with patterns in hierarchy. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was declared not subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee at the LUMC, Leiden, the Netherlands (Protocol number: N19.026), and was approved in all participating centres in which professionals had their practice. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

Participants

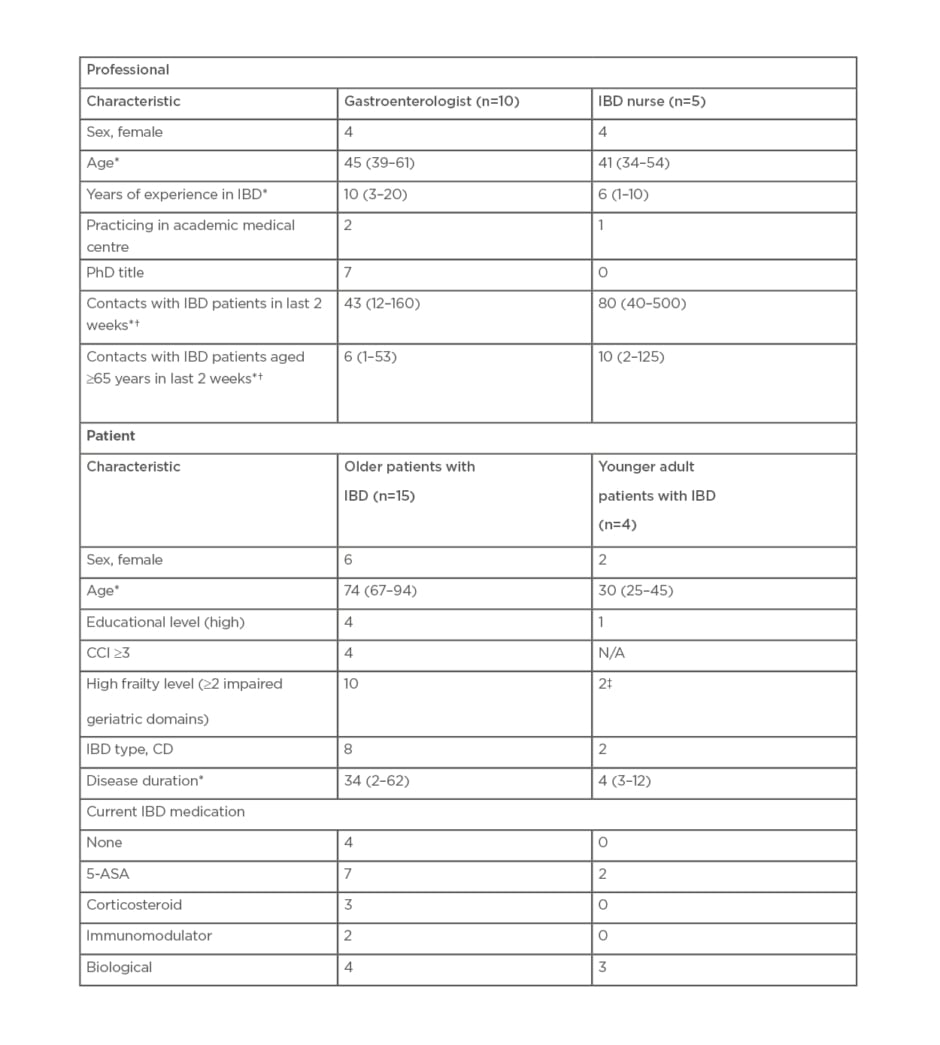

In total, 34 interviews were conducted in 15 professionals, 15 older patients, and four younger patients. For the interviews with professionals, the authors approached 15 gastroenterologists and 10 IBD nurses, of whom 10 and five, respectively, participated. Three gastroenterologists did not want to participate due to lack of time, and two gastroenterologists and three nurses did not respond. Two nurses wanted to participate but could not be included for logistical reasons. The interviews with professionals lasted between 27 minutes and 51 minutes. Gastroenterologists had a median age of 45 years, ranging from 39 years to 61 years. IBD nurses had a median age of 41 years, ranging from 34 years to 54 years. The years of experience in IBD care in professionals ranged from 1 year to 20 years (Table 1).

For the interviews with patients, 20 older patients with IBD were approached, of whom 15 participated. Two older patients were not willing to participate, one patient did not speak Dutch, and two patients could not be reached. Eight patient interviews took place at the LUMC, one interview took place over the telephone due to COVID-19 restrictions, and the remaining interviews took place at the patients’ homes. During three interviews, a spouse or child was present. Interviews took between 37 minutes and 69 minutes. Patients had a median age of 74 years, ranging from 67 years to 94 years. Disease duration ranged between 2 years and 62 years, and patients used different IBD medications at the time of the interview. Four patients had a high comorbidity level as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), 10 patients had two or more impaired geriatric domains in their geriatric assessment, and were therefore classified as frail (Table 1). Five younger patients with IBD were approached and included. However, one patient withdrew consent due to disease severity. Sociodemographic and disease characteristics of younger patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Participant characteristics.

*Median (range).

†At outpatient or inpatient department, during telephone consultation or supervision.

‡Considers itself frail.

CD: Chron’s disease; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; IBD: inflammatory bowel diseases; NA: not applicable; 5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylates.

Professionals

Therapy goals in treatment of older patients with inflammatory bowel disease according to professionals

The authors asked professionals what goals they aim for in the treatment of older patients with IBD, and whether these goals differ from those for younger patients. Some professionals said they aim for the same goals in older versus younger patients with IBD. However, other professionals stated that they aim for different therapy goals in older patients with IBD.

Regarding disease-related goals, a number of professionals stated that clinical remission was often more important, whereas endoscopic remission and mucosal healing were reported to be less important in older patients. The prevention of long-term complications was considered to be less important in older patients, and some participants tended to treat older patients with IBD less aggressively. This was motivated by some professionals’ belief that disease course is more indolent in older patients. “Free of symptoms, with the least possible amount of immunosuppression, yes that’s it. And the presence of biochemical remission or mucosal healing, that really doesn’t matter much to me,” said one gastroenterologist (number 6)

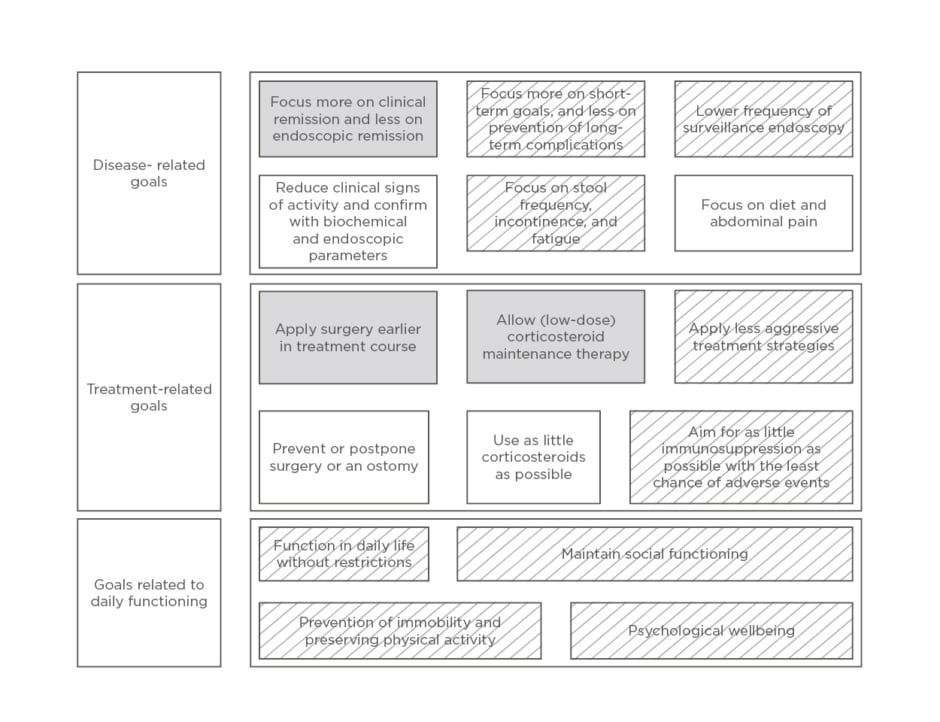

Second, other treatment-related goals in older patients with IBD were named. Professionals reported to aim more towards remission with as little immunosuppression as possible in older patients, and to prescribe medication with as few adverse events as possible. When remission is achieved, a couple of professionals declared to stop maintenance therapy sooner in older patients. Sometimes, professionals tended towards surgery earlier in the treatment course in older patients compared with younger patients. One professional mentioned to aim for as little burden for the older patient as possible by reducing hospital visits. Third, goals related to daily functioning were identified. Professionals put more focus on functioning in daily life, preventing social isolation and immobilisation, and retaining physical activity in older than in younger patients. An overview of therapy goals is depicted in ([Hl]Figure 1[/hl]).

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of therapy goals in the treatment of older patients with inflammatory bowel diseases as compared to younger patients, according to professionals and patients.

Regarding patients’ answers, both quality of life goals and therapy goals were incorporated in this figure.

Grey: named by professionals; white: named by patients; grey and white shaded: named by both professionals and patients.

All professionals included clinical remission or corticosteroid-free remission in their top three therapy goals. More than half of the professionals did not put endoscopic remission in their top three. For younger patients, most of the professionals would rank endoscopic remission higher. Some professionals would rank corticosteroid-free remission higher in younger patients versus older patients. In contrast, other professionals would rank it lower.

“Corticosteroid free remission, it depends on the case. In younger patients it would be number one priority, in older patients we will sometimes accept low doses,” stated one gastroenterologist (number 3).

“Definitely no [corticosteroid] maintenance therapy. I think that is just not right,” said another gastroenterologist (number 8).

When looking at therapy goals related to daily functioning, preservation or restoration of independence and mobility was most often chosen for the top three hierarchy. Next, the authors asked if and how the presence of geriatric impairments in an older patient, such as impaired functioning in daily life, cognition, and independence, or the presence of multiple comorbidities, would change their ranking of goals. Clinical remission remained the most important therapy goal for most of the professionals, regardless of geriatric impairments. Professionals said that this is the goal they can influence the most. Some professionals chose to strive more towards preservation or restoration of independence and mobility if those were impaired in patients. One professional said that impairments in mobility or functional status could be a reason to choose an ostomy, as incontinence could be more disabling in those patients. A few professionals said that corticosteroid-free remission was less important to them in an older patient with geriatric impairments. However, other professionals said to aim for corticosteroid-free remission, no matter which impairments were present. Some said they put even more emphasis on corticosteroid-free remission when there were multiple comorbidities or an impaired cognition.

“If a patient has dementia and it’s all about maintaining quality of life, and we achieve quality of life with clinical remission, then I won’t worry about whether this patient does or doesn’t use corticosteroids,” revealed one gastroenterologist (number 1).

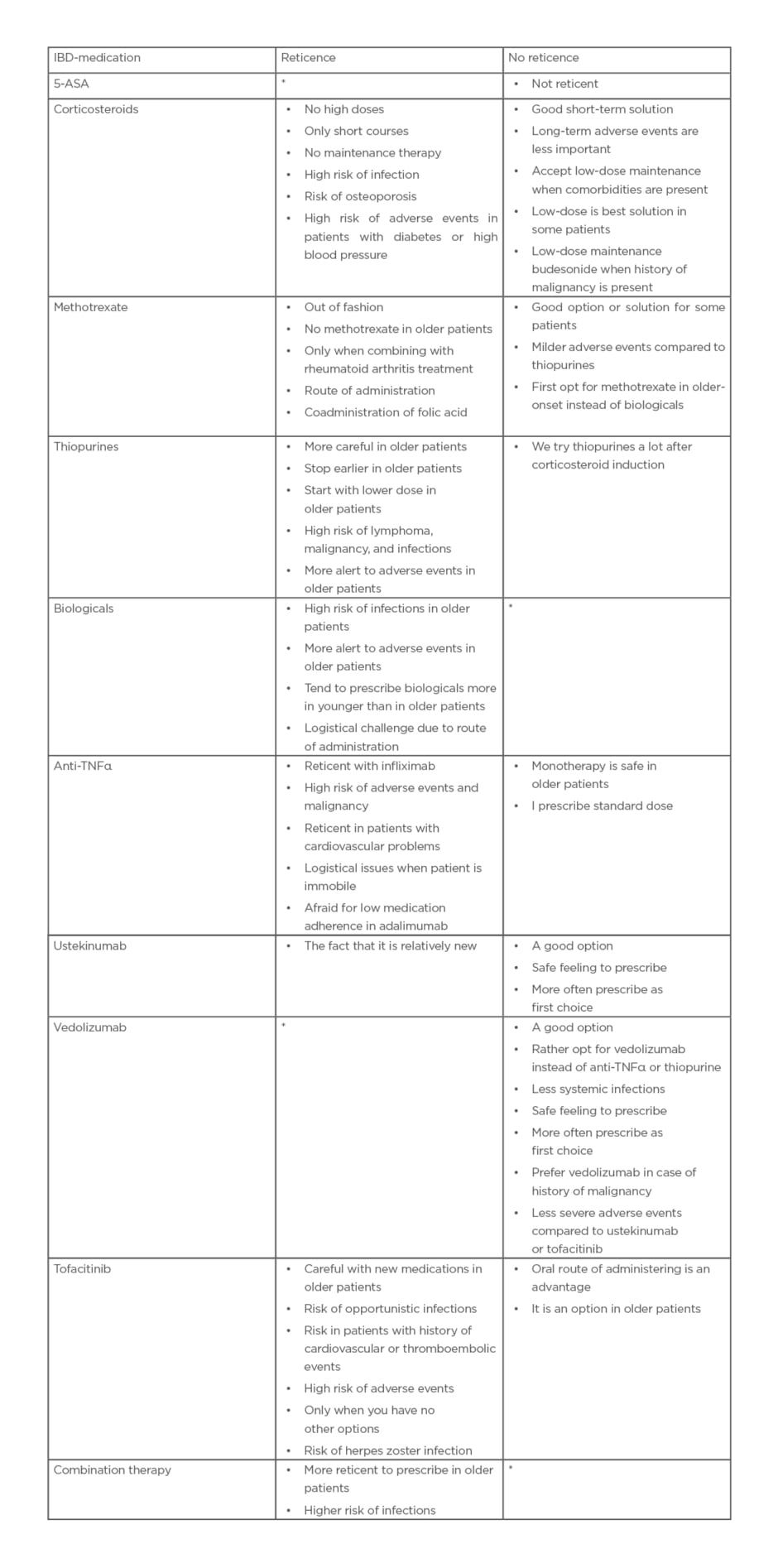

Preferences in inflammatory bowel disease medications among professionals

After asking about patient characteristics and therapy goals, the authors asked professionals if they were reticent in prescribing certain IBD medications in older patients. The results of this question are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2: Reticence in prescribing medication in older patients with inflammatory bowel diseases.

Table reflects the answers of professionals (gastroenterologists and inflammatory bowel disease nurses) to the question: “Are there IBD medications you would prefer not to prescribe in older patients with IBD, and if so, which and why?” After 6/15 interviews, the authors started asking professionals specifically about corticosteroids, methotrexate, and tofacitinib.

*When no comments were made about reticence or preference in older patients columns were left blank in the table.

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylates.

Aspects of frailty in older patients with inflammatory bowel disease according to professionals

First, the authors asked professionals if they make a distinction between fit and frail patients in daily clinical practice. Thereafter, the authors elaborated on how this distinction was being made and whether this influenced choice of treatments or therapy goals. A couple of professionals mentioned paying attention to frailty. The way frail patients were identified varied from applying a clinical view to estimating biological age or life expectancy. None of the professionals reported to assess frailty in older patients with IBD systematically, or to apply validated frailty screening tools. Somatic aspects of frailty were most often mentioned, primarily comorbidity but also polypharmacy and malnutrition. Furthermore, a lot of professionals acknowledged functional status, such as living in an assisted home facility and not being able to perform activities of daily living, as an important aspect of frailty. A few professionals stated that therapy goals should be based on the presence of frailty; for example, preventing surgery in older patients with frailty. However, others said that patients with frailty presenting with a flare-up of IBD should be treated the same as other patients.

“Therapy goals will be different and they depend on how many aspects of, yes, frailty are present. We don’t ask specific questionnaires regarding frailty yet; I think actually we should do it in older patients,” commented one gastroenterologist (number 3).

Patients

Quality of life and therapy goals according to older patients with inflammatory bowel disease

First, the authors asked patients about factors determining quality of life. Aspects of functional status were mentioned most often; patients considered their ability to function in daily life and mobility to determine their quality of life for a large part. Second, patients were asked about their therapy goals in IBD. Therapy goals were again specified into disease-related goals, treatment-related goals, and goals related to daily functioning. Disease related goals were mostly absence of inflammation, in general or as seen during endoscopy, and decrease of IBD symptoms, of which stool-related symptoms (stool frequency, incontinence, and diarrhoea) and abdominal pain were named most often.

“I mean, he didn’t dare to go anywhere, not even to a birthday party. He was just too scared he could not make it to the toilet and would be incontinent in front of his friends. So that is what really made live a very solitary life,” commented the daughter of patient (number 8).

Themes identified as treatment-related goals were mostly surgery- and medication-related. Surgery-related goals included preventing or postponing surgery and preventing an ostomy. The patients who already had an ostomy reported to strive towards good functioning of the ostomy. Medication-related goals were finding the most effective medication with the least possible adverse events, aiming for no medication or as little medication as possible and a treatment without corticosteroids. Themes related to functional status, such as being able to function as normally as possible, were mentioned most often when looking at goals related to daily functioning. Younger patients added therapy goals related to the ability to work and the ability to have a successful pregnancy.

When asked to rank the cards with therapy goals, almost all patients ranked clinical remission in their top three. Patients stated that reducing IBD complaints was important because this leads to less disability, more independence, and a better quality of life. Almost all patients also ranked a decrease in inflammation assessed by blood or stool tests or endoscopy in their top three. Considerations mentioned here were the fact that a decrease in inflammation as seen by objective markers led to an in increase in general health and a decrease in IBD complaints. Moreover, patients said that having certainty about the severity of inflammation as measured by objective parameters or the presence of polyps was important to them. A large proportion of the patients strived towards goals related to daily functioning, such as preservation or restoration of independence, good memory, positive mood, and social contacts. Patients selecting those goals as most important were of advanced age, frail, and had multiple comorbidities. Conversely, patients selecting disease-related goals as their top priority were often of lower age, less frail, and had little comorbidities. Almost half of the patients put striving towards remission without the use of corticosteroids in their top three therapy goals. Their considerations included negative experiences with corticosteroids in the past and the high risk of adverse events. Younger patients mainly prioritised objective markers of disease; only one younger patient selected “Reducing IBD complaints” in their top three hierarchy. Younger patients who considered themselves frail more often selected goals related to daily functioning.

Aspects of frailty in inflammatory bowel disease according to patients

Almost all older patients had a positive experience with the geriatric assessment performed during the authors’ cohort study. One patient said she felt fooled when undergoing the cognition questionnaire. Many patients thought that a geriatric assessment should be part of standard care. Reasons were first because it could add to the early detection of geriatric impairments. Second, patients thought it would be helpful to optimise therapy goals. Third, it could help tailor individual care, such as by providing written explanations when cognitive impairment is present. Suggestions for further extension included repeating the assessment every couple of years to monitor functional decline. Younger patients did not undergo a geriatric assessment; however, suggestions were given by them to perform a geriatric assessment not only in older patients but also in younger patients, as younger patients could also be frail.

“Someone who is physically very weak and tells a story about what he cannot do anymore, for me, it would be a very big decline, but for someone else it could be a very reasonable way of living. I think this can differ a lot per person,” noted one patient (number 10).

The aspects of frailty that were identified by patients with IBD were largely related to functioning in daily life, such as being able to do everything yourself and being able to walk and move without falling. Also, aspects of comorbidity were often mentioned, such as having other diseases, having pain in general, or having a hearing impairment. Polypharmacy was named as being an aspect of frailty because medications could lead to adverse events. Impaired mental status, namely depression and anxiety; impaired cognition; and the inability to cope with negative events was also supposed to influence frailty in a negative way. The presence of social support and informal caregivers was deemed to affect frailty in a positive way. Being of advanced age was mentioned by a couple of patients. Many patients mentioned their IBD as an aspect of frailty, especially in case of a flare-up, incontinence, or diarrhoea, or when they have to pay attention to what they can and cannot eat. Also, feeling fatigued was mentioned as an aspect of frailty. The two patients who had an ostomy at the time of the interview mentioned their ostomy as an aspect of frailty. Patients mentioning functioning in daily life and being able to do everything yourself were all frail, while patients mentioning IBD-related aspects of frailty were mostly less frail. The interviews in younger patients did not yield new aspects of frailty.

DISCUSSION

Current evidence in IBD points towards different treatment regimens being used in older patients compared with younger patients.7-13 Therefore, the authors aimed to study factors contributing to the differences in treatment between older and younger patients with IBD, and the relation between frailty and therapy goals, from the perspectives of both professionals and patients with IBD. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study allowing for perspectives of both professionals and patients, thereby creating a comprehensive conceptualisation of the treatment of IBD in an older population.

In both professionals and patients, the authors noted that therapy goals in older patients differed from those in younger patients. A variety of themes were generated on this topic and are presented in Figure 1. Firstly, a lot of professionals mentioned to aim more for clinical remission in older patients compared with younger patients, and put lower priority on endoscopic remission. Although older patients themselves were also focused on clinical remission, a lot valued confirmation of remission by objective markers as a reassurance. Secondly, the authors noted a discrepancy regarding surgery. Some professionals stated that they opt for surgery earlier in the treatment course of older patients, while older patients themselves strived towards postponing or preventing surgery and an ostomy. A couple of patients explained that they believed themselves to be too old for surgery and were afraid of becoming dependent on caregivers or nursing aid after surgery. Thirdly, in professionals, the authors found diverging opinions on the use of corticosteroids in older patients with IBD. Some stated to allow low-dose maintenance therapy in older patients, while others were reluctant to even prescribe them short courses of corticosteroids. These views were in contrast with those of patients, who were quite uniform in preferring to avoid corticosteroids. Patients explained that this was mainly based on their earlier negative experiences with corticosteroids. This finding is in line with a study by Asl Baakhtari et al.,23 who investigated factors making patients with IBD less willing to take corticosteroids.

Furthermore, the authors found a lot of considerations in professionals regarding reticence or preferences in prescribing IBD medications in older patients, as depicted in Table 2. Interestingly, little to no reticence with regards to prescribing ustekinumab or vedolizumab in older patients was present. This finding is in agreement with the results from a case-based survey, which found that vedolizumab was the preferred first-line agent in the treatment of older patients with steroid-dependent, moderate-to-severe UC.²⁴

Both the above-mentioned differences in therapy goals and the experienced reticence in prescribing IBD medications are factors contributing to the use of different treatment regimens in older versus younger patients.

Some professionals said to account for frailty, but none of the professionals assessed frailty systematically. At the same time, professionals reported that the presence of aspects of frailty influences therapy goals and treatment modalities. Professionals said to prioritise functional-related goals, such as maintaining self-dependence and mobility, in older patients with a low level of dependence or impaired cognition. In older patients with aspects of frailty, some professionals put higher priority on corticosteroid-free remission and others lower priority compared with older patients without aspects of frailty. Some said to aim more for the prevention of surgery, while others said that in older patients with frailty, they would opt earlier for an ostomy. The fact that frailty status influenced therapy goals and treatment was in line with considerations provided by patients, as patients with frailty more often gave priority to goals related to frailty, which was also found in younger patients who considered themselves frail. This could suggest that frailty status is more important than age in the treatment of IBD.

Both professionals and patients emphasised that clinical remission remained important, independent of non-IBD characteristics. This is because professionals can influence this goal the most. Moreover, for patients, a decrease in complaints automatically leads to an increase in independence, especially regarding decrease of stool incontinence.

Many different aspects of frailty were identified, thereby illustrating that frailty is a heterogenous concept. It was remarkable to see that a lot of patients mentioned disease-related aspects, such as the presence of a flare-up or incontinence. This underlines the importance of IBD symptom control in older and frail patients with IBD. Frailty is a concept best measured by performing validated screening questionnaires25,26 or a complete geriatric assessment.6 The lack of implementation of frailty measurements in current daily practice is illustrated by the ways frailty is currently measured. Indeed, current studies on frailty in IBD retrospectively assess frailty using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes and not by clinically applicable measurements.15,27-29 Therefore, the gap between scientific evidence and daily practice is still present. In older patients who are candidates for intensive treatments such as chemotherapy or major surgery, implementation of a routine clinical care pathway provides the opportunity to study associations between characteristics of frailty and treatment outcomes.30 In older patients with IBD, applying such standardised frailty screening prior to starting therapy could also guide decision making and support individualised treatment.

A couple of qualitative studies describing patient perspectives on IBD treatment have been performed,33-35 and also in other autoimmune diseases.34,35 However, this study is the first to investigate the opinion of both gastroenterologists and older patients on IBD treatment and the concept of frailty. Involving older patients with multiple conditions or frailty in the decision-making process could be challenging because of the potential for competing outcomes.36 Nevertheless, Fried et al.37 found that it was feasible for older patients to prioritise preferences in health outcomes by asking older patients to rank outcomes on a visual analogue scale. The resulting conceptualisation of the authors’ study therefore delivers important lines of approach for further research and treatment of older patients with IBD. By using semi-structured interviews, open questions allowed in-depth exploration while the use of cards yielded additional information and considerations. A couple of studies have been published on the association between frailty and readmissions, infections, and mortality.27,29 In this study, the authors explored current modalities of frailty measurements and what both professionals and patients consider to be aspects of frailty.

This study delivers important lines of approach for both daily practice and further research on IBD in older patients. Goals named by professionals and patients could be used in research including older patients with IBD. Likewise, considerations regarding different treatment strategies in older patients could be used in surveys to assess current opinions on a larger scale.

This study also has some weaknesses. All participating patients were under treatment in an academic hospital, and could therefore have a more severe IBD history. However, this effect was minimised by applying purposive sampling and thereby reaching maximum variation. Participant size of the authors’ study was small, which is inherent to the qualitative study design. Because of the small sample size, certain themes could have been missed. The authors tried to prevent this by assessing data saturation. When no new ideas or themes emerged in three successive interviews, the authors concluded that data saturation had been reached. Both professionals and patients could have given socially acceptable answers during interviews. This response bias was minimised by the fact that the interviews were conducted by medical students who had no prior relation with the participants, and participants were not informed on the questionnaires beforehand.

CONCLUSION

The authors found that many therapy goals differed between older and younger patients, in both professionals and patients. Besides, professionals did not assess frailty systematically, yet aspects of frailty influenced therapy goals, thereby exposing the gap between current evidence and daily clinical practice. The authors believe that the variation in professionals’ therapy goals found in this study reflects the lack of evidence on most effective treatment strategies in this heterogenous population. The results of this study further underline the need for a systematic assessment of frailty in individual patients and collection of evidence on optimal treatment of frail patients.