Endoscopic transmural drainage of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections (PFC) using lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) has become common practice.1 However, recent studies have raised concerns for potential delayed adverse events (AE) associated with prolonged indwelling LAMS, including delayed bleeding and the phenomenon of ‘buried stent syndrome’, in which extensive mucosal tissue overgrowth around the flanges of the stent compromises stent removal during follow-up.2 Based on these observations, the current guidelines by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommend the retrieval of LAMS within 4 weeks to prevent stent-related AE; however, the ESGE recognise that this is based on low-quality evidence.3

Establishing the incidence and type of delayed AE associated with LAMS has direct clinical ramifications on the follow-up strategy for patients with pancreatic walled-off necrosis (WON) and pancreatic pseudocyst (PP). The objective of our study was to perform a multicentre retrospective analysis to assess delayed AE with LAMS and to identify potential predictors of treatment failure and delayed AE.

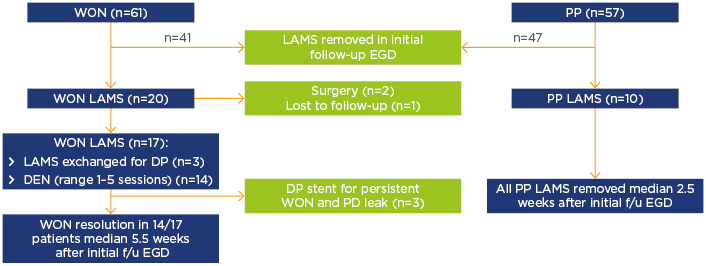

A total of 122 patients (64 WON and 58 PP) underwent LAMS placement. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, BMI, or American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade between patients with WON versus those with PP. Successful LAMS insertion was achieved in 98% of patients in both groups (p=1.0). Mean size of PFC was similar for WON (131±44 mm) versus PP patients (95±48 mm; p=0.6). Follow-up imaging was performed at a median of 4 weeks after LAMS insertion. PFC resolution was significantly higher for PP patients (97%) compared with WON (62%) (p<0.001). Stent occlusion was the most common delayed AE identified (18% of PP patients and 30% of WON patients; p=0.13) at follow-up endoscopy performed at a median of 5 weeks after LAMS insertion. Overall, there was only one case of delayed self-limited bleeding at the time of stent removal, and in two patients the LAMS was partially buried but were retrieved without difficulty. A flow chart of the patients included in this study is depicted in Figure 1. Use of electrocautery-enhanced LAMS was the only factor associated with treatment failure of WON (objective response: 13.2; 95% confidence interval: 3.33–51.82; p = 0.02) on logistic regression. There were no patient, operator, or procedure-related factors predictive of stent occlusion.

Figure 1: A flow chart of lumen-apposing metal stent removal and subsequent follow-up.

DEN: direct endoscopic necrosectomy; DP: double pigtail; EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy; f/u: follow-up; LAMS: lumen-apposing metal stents; PP: pancreatic pseudocyst; WON: walled-off necrosis.

In summary, our study demonstrates that LAMS are safe and effective for the treatment of PFC. Delayed bleeding or buried stent syndrome was seldom seen in our study. Most cases of PP resolve within 4 weeks and, therefore, early stent removal can be achieved without compromising the efficacy of the intervention. Conversely, as shown in this study, many cases of WON persist at 4 weeks after LAMS placement and early stent removal may simply not be feasible for these patients. Given the current wide variation in clinical practice, particularly for patients with WON, we urgently need high-quality, controlled studies to evaluate the role and timing of adjunct strategies (e.g., endoscopic necrosectomy, additional stenting through LAMS, multigate drainage) that may expedite PFC resolution and facilitate early LAMS removal.