Are public-private partnerships set to be drivers of innovation across the pharmaceutical industry? GOLD explores how these collaborations are formed and maintained, as well as their limitations and future potential

Words by Cheyenne Eugene

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) create fertile prospects spanning countries, oceans and continents that are ripe for innovation. They take varying shapes: changing or implementing policies, streamlining different regulatory structures across nations or sectors, creating R&D-friendly environments, and much more besides.

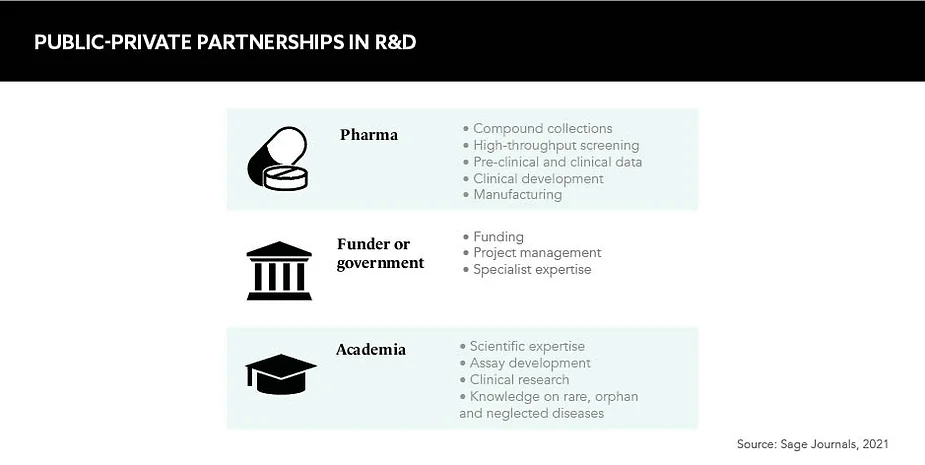

In the life sciences, stakeholders range from pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology firms to academic institutions and governments, all with different ambitions and incentives. “There’s no natural collaboration point between them,” explains Claire Skentelbery, Director General, EuropaBio. “You’ve got an incredibly complex set of skills, technologies and processes that come together from types of organisations that are often extremely remote to each other and don’t interact a lot.” In short, PPPs have the power to unify diverse stakeholders with different motivations under a common goal.

PPPs are often focused within a pre-competitive landscape, aiming to maximise potential, mitigate risk and offer a safer place to collaborate. This is their key selling point, according to Skentelbery. Promising scientific breakthroughs can be stopped in their tracks if they do not hit the correct regulatory standards, and PPPs offer that all important set of checks and balances, while also empowering researchers, patients and companies to be more successful in their endeavours. “It’s not about just making a new technology, it’s not about having another policy, it’s about solving a structural bottleneck,” highlights Skentelbery.

Experts in the field indicate no regular or specific initiator of PPPs but suggest coalitions will form when a challenge arises that can only be solved through a public and a private entity working together. Even then, “collaboration doesn’t happen spontaneously”, Skentelbery remarks. In Europe, schemes such as the Innovative Health Initiative and the EIT Health network, aim to facilitate multi-stakeholder exchanges and engagements, and it’s these discussions that often lead to PPP proposals being formulated.

Limitations and prerequisites

There’s no denying that PPPs are complex beasts and, naturally, there will be sacrifices to make on all sides. Stakeholders, and their objectives, will differ widely and an obvious key point of friction is around intellectual property rights and ownership. “PPPs do a fantastic job, but cannot be all things to all people,” says Skentelbery. “You come to an acceptable middle.”

It’s not about just making a new technology, it’s not about having another policy, it’s about solving a structural bottleneck

Léa Perles, Lead Strategic Marketing and External Opportunities, Brenus Pharma, agrees with this sentiment and acknowledges that there are multiple hurdles to these negotiations. “It is very challenging to set a fair and appealing framework for a partnership when there is such a difference in the interests, needs and structures of all involved partners.” Offering advice on how to avoid these limitations, Perles suggests the adoption of “proactivity and adaptability”.

In addition, the time frames needed for these collaborations in comparison to other cross-industry unions raises concerns for some stakeholders. “It’s not going to be fast,” Skentelbery asserts simply, before clarifying that this is “just the side effect” of their complexity and so they need to be given the necessary time. As the next generation of healthcare is being built by PPPs, it should not be expected to arrive tomorrow, but when it does arrive, it will be fruitful. “This is about building a 50-year ecosystem for the better,” Skentelbery adds.

Slow progress isn’t absolute, however, and Perles points out that different “partners have different paces”. Typically, if a change needs to be achieved very quickly, it will not be realised through a PPP. There are exceptions to this, of course, such as the development and dissemination of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics, but Skentelbery explains that while “PPPs can be moved into high gear for specific challenges, that’s not the normal operation, it’s not what they were designed to do”.

What’s more, PPPs are not necessarily the right vehicle for some types of organisations and projects. If, for example, a company has a very high dependency on short-term cash flow, including some small and medium-sized enterprises, then it would be a mistake to prescribe a PPP to resolve its challenges.

PPPs have the power to unify diverse stakeholders with different motivations under a common goal

However, if circumstances dictate that a PPP is a suitable option, then trust, commitment, determination and confidence are widely acknowledged as key ingredients for success. “If you don’t build a framework in which everybody is confident, it’s not going to get over the starting line,” warns Skentelbery. And Perles supports this perspective, adding: “Developing a trustful and collaborative mindset across the partnership helps to maintain engagement along the project, which can be difficult sometimes.”

Ensuring sound legal and financial frameworks is also integral to protecting this environment of trust. “These de-risk collaboration, particularly where you’ve got partners with very sensitive information that they’re going to bring to the table,” Skentelbery explains.

The future of PPPs

The potential of PPPs is vast and many experts, including Skentelbery, predict that they could unlock Europe as an innovation superpower by harmonising processes for data sharing. Focusing on what this could mean for pharma, Perles says: “The industry already has tremendous amounts of data and does not fully take advantage of it.” The development of digital solutions will therefore be crucial, particularly for areas such as rare diseases where isolated data needs to be pooled in order to be leveraged.

Another direction industry experts see PPPs moving toward is global inclusivity. “Wealthier areas, like the US and Europe, still have some work to do to make sure that the rest of the world is taken on board,” comments Skentelbery. Alluding to vaccine nationalism and territorial sovereignty during the COVID-19 crisis, she says that “there is no doubt that sections of the world were left behind”, and “Europe and the US have a moral responsibility” to prevent this dynamic from perpetuating.

While the complex nature of PPPs leads to inevitable limitations, they ultimately offer the chance to de-risk collaboration and address systemic bottlenecks that are preventing progress. Public health and chronic diseases still face many closed doors – ones that require a hoard of different keys to unlock – but as Skentelbery puts it, PPPs allow “a lot of very different people, all with the right, but slightly different keys, to open the door at the same time”.