The pharmaceutical industry is being urged to take action to bridge the access gap for women with gynaecological cancers, but what steps need to be taken to achieve this?

Words by Jade Williams

On 26 June 2023, the UK’s National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) announced with “pride and regret” that it would be closing its doors after 22 years. The body, which was set up to help cancer research funders best target their investments, has fallen on hard times amid the uncertain economic and research landscape.

As well as being a great loss to oncology research in general, the closure of the London-based research institute will deal a blow to what is known as healthcare’s ‘silent killer’ – gynaecological cancers. As one of the NCRI’s strategic priorities, it had a dedicated group to identify key areas of need in this area. It’s also a field that is in urgent need of investment.

The NCRI is one institution in one country, but what if more closures are on the horizon? The pharmaceutical industry needs to step up its investment in gynaecological cancers and develop strategies to secure more women access to cutting-edge treatments.

Ramp up research funding

Unlike breast cancer research, which has the lion’s share of the pharma industry’s attention in women’s health, research and funding for gynaecological cancers is comparatively low. This is not surprising given the polar incidence rates for each cancer type, but it is worth remembering that gynaecological cancers are the fourth greatest cause of cancer death in women each year.

“As the number one incidence of women’s cancers, breast cancer funding is obviously quite high,” comments Christy Siegel, General Manager, Breast and Women’s Cancers Portfolio, Novartis US Oncology. “There’s been a modest increase in research for other women’s cancers, but it’s still not to the same degree as breast cancer.”

This discrepancy in funding extends to the allocation of public resources as well. Cancer Research UK, for instance, dedicated £23m to breast cancer research between 2021 and 2022, in contrast to the £9m allocated to ovarian cancer research and a mere £1m each for cervical and endometrial cancers. While the higher incidence of breast cancer justifies the funding it receives, gynaecological cancer research is calling out for more investment.

Deal with clinical trial disparities

Another aspect of gynaecological cancer care that could use an overhaul is clinical trial enrolment. In a recent study on precision oncology clinical trials for gynaecological cancers, only 61 out of 493 trials met their inclusion criteria.

The industry is trying its best to attract more people from minority groups, but models need to be revised to recruit diverse patient groups. Non-Hispanic black women, for example, are less likely to get ovarian cancer than women of other races, but they are more likely to die from the disease than most other groups. The result? Worrying disparities in mortality rates.

However, the solutions are not simple: barriers to clinical trial access for ethnic minority groups include lack of childcare or transport to trial sites from deprived areas. If the industry is to better serve patients, it needs to simplify the clinical trial process, including by using telehealth and adding linguistically and culturally appropriate patient navigators to trials.

Another challenge is the location of most gynaecological cancer trials, with these only being run in a handful of countries. “Unfortunately, even today, many of the industry’s clinical trials are still conducted largely in more developed countries predominantly residing in the Global North,” comments Viraj Rajadhyaksha, Area Medical Director, AstraZeneca.

Even today, many of the industry’s clinical trials are still conducted largely in more developed countries

He notes that “trials need to expand to regions such as South-East Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa to ensure clinical data is more representative of the populations the industry aims to serve, helping to ensure equitable health outcomes for all”.

This is a challenge that needs to be addressed as not actively recruiting a diverse cohort of patients into clinical trials means that women from ethnic minority groups are losing out.

Improve access to targeted treatments

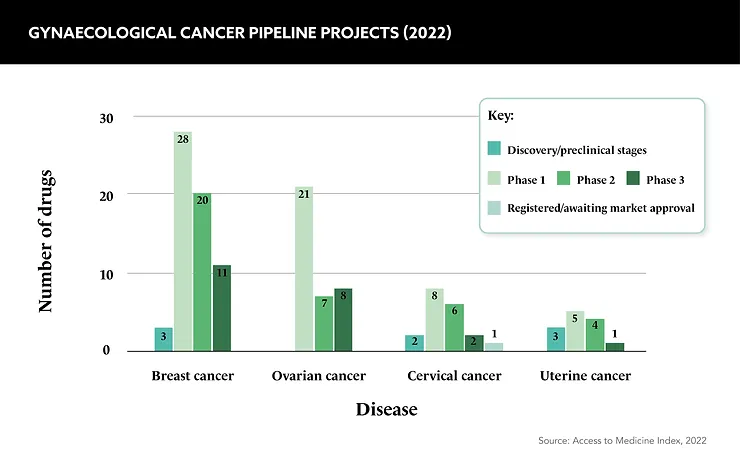

Despite some gaps in funding and research, the last decade has seen an explosion of innovation in gynaecological oncology. Acknowledging the success, the International Journal of Gynecological Cancers labels the level of innovation as “unprecedented”.

New therapies to hit the market include therapeutics targeting DNA damage repair, immune checkpoint inhibitors and antibody-drug conjugates. These are considered the most revolutionary cancer treatments as they use patient biomarkers to identify weaknesses in cancer cells and attack them.

While the availability of targeted medicines is clearly a positive development, the journey from bench to bedside can be complex and unfruitful. For example, in a sample of 99,286 ovarian cancer patients diagnosed between 2012 and 2019, only 4.1% received targeted therapies. While surgery or chemotherapy is often the first course of action, this treatment level is clearly much lower than industry would like.

One barrier for broader access to targeted drugs is the apparent high cost of new medicines. Rajadhyaksha believes “it is one of the roles of the pharmaceutical industry” to address through partnerships with the government, payors and private insurers to address these challenges. By working on ways to balance innovation with effective access strategies, it could be possible to reduce gynaecological mortality rates for some patients.

Find a role for medical affairs

Any access strategy must benefit the many, not the few, and there is another way industry can help bolster access to innovative therapies and improve outcomes.

It is vital for industry to work with healthcare providers to promote the positive impact of genomic screening and profiling in gynaecological cancer, and medical affairs teams are well placed to lead the way. Currently, there are gaps in knowledge and education, which means not all patients are being quickly diagnosed or receiving the best treatments.

The diagnosis challenge was highlighted in a study published by Cancer Research UK and NHS Digital in February 2023, which found that women from ethnic minorities are diagnosed with gynaecological and other cancers later than their white counterparts.

More specifically, Caribbean women in the UK were to be more likely to be late diagnosed with gynaecological cancers, while African women are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage breast, womb, bowel and ovarian cancers.

In line with these inequalities in diagnosis, many women are not advised on the best treatment options, often due to the healthcare postcode lottery. Medical affairs teams can help by providing more information, resources and support on treatment choices. This includes extending their educational reach into minority and less urban communities.

As Siegel argues: “A key job to be done by medical is to help facilitate that ecosystem to help educate [healthcare] practices that are either more rural or just more community based to really understand: what does cutting-edge care look like for gynaecological cancer?”

What does cutting-edge care look like for gynaecological cancer?

Prioritise the patient experience

Creating better access to treatments for people with gynaecological cancers is an ethical imperative for the pharma industry, but this is only one part of the picture. Companies in the space must try to tackle the mental and emotional burden on patients as well.

“Pharma has a responsibility not only to help patients live longer, but also to help them live better – just being alive isn’t enough,” says Siegel. “The pharmaceutical industry has an obligation to support the patient holistically – the emotional and physical (including sexual) aspects of their journey.”

The emotional burden of cancer can be enormous for patients as they go through diagnosis and treatment. In this therapy area in particular, treatment can sometimes involve the removal of organs, such as hysterectomies, which can affect a patient’s sense of identity.

As a result, the industry should work with HCPs to address the emotional needs of patients and ensure that they receive comprehensive care that goes beyond medical interventions. It can and should contribute to a more patient-centered approach.

Pharma has a responsibility to not only help patients live longer but also live better – just to be alive isn’t enough

It is sadly the case that many patients with gynaecological cancers don’t live long enough to become patient advocates, Rajadhyaksha concludes. So while many people with lung or breast cancer “have stories to share” those stories “will not exist here”, he admits.

So, with this in mind, it is integral that the pharma industry works with healthcare systems to improve inequalities, access and follow-up care for patients. It is time to give all people with gynaecological cancers the care and voice they deserve.